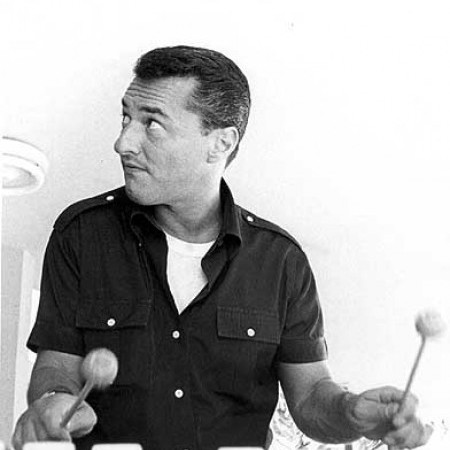

Terry Gibbs

It wasn’t long before Gibbs found a new home for the band. This club was also on Sunset Boulevard, called the Sundown, where the band began working Mondays and Tuesdays every week. Soon after, Sunday nights were added.

With time out for a fortnight at the Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas, Nev., the Gibbs band remained based at the Sundown for 18 months. Las Vegas was as far east as it ever traveled. For that engagement, Gibbs said, the band was paid $5,000 a week; by the time all the expenses had been settled, he wound up with $111 at the close of the job. “But,” Gibbs added, “it was worth it. We had Jimmy Witherspoon with us at the Dunes, making it even more of a ball.”

While Gibbs concentrated on building the band, his bank account took a heavy beating.

“I had to give up so much work with the quartet,” he explained, “that I figured it was costing me $1,000 a month to keep the band going. In all, I had to give up about $20,000 in work with the quartet. During the previous years, when tax time came around, I always had to come up with additional money for Internal Revenue. The one year I had the band working study, I got back a check for $1,100 from the government.

“But I’ve been in this business 31 years, and I’ve never been so happy losing money in my life.”

Although the band presently is without a home or any reasonable facsimile of steady work, Gibbs refuses to abandon his idée fixe. He has almost 100 arrangements in his library at present, and the albums will shout on. The latest, Explosion, on Mercury, will be released shortly.

Meanwhile, the “guys in the band”—Gibbs refuses to use the term “sidemen”—are standing by in Hollywood, most of them busy with studio work, while the vibist tours with the quartet in the East.

“I must work with my little group,” Gibbs insisted. “I love working with the quartet. Eventually, I want to have a quartet within the big band but not made of some of the guys in the band. A separate group.

“And I’m looking for a singer. Probably a girl singer. And I don’t know yet what I’d like her to sound like—but I’ll know when I hear her.

“I’m going to see what I can do with the big band in the East. Then, if I see something promising, I’m going to call Mel Lewis and the rest of the guys. Of course, it depends on the money I have to work with, so it’s very hard to predict what’ll happen.”

Gibbs’ “guys in the band” constitute a unique group in that they are, to a man, musicians skilled in the most exacting studio work, and most derive their livelihoods there-from, yet they retain a genuine jazz freshness both as individuals and a unit.

“It’s a fun band,” Gibbs said. “For example, during our first few tunes of the evening, when the place isn’t crowded, the guys applaud one another when they play solos. It’s like a ball club. When a player hits a home run, he gets a pat on the back. It’s that way in the band.”

Mel Lewis, the time-keeping cornerstone of the Gibbs band, made the following flat statement: “This is the greatest swing band I’ve ever played in.”

“It saved my life, musically,” the drummer continued, “and the same goes for the rest of the guys.”

“Who was hiring big bands to work in L.A. clubs,” Lewis asked rhetorically, “before we went to the Seville? Since then, several big bands have worked clubs in L.A., but we were the only band that did any business in a club. We started the big-band era in Los Angeles.”

Gibbs outlined the most important ingredients in a musically successful big-band.

“A drummer!” he explained. “A good drummer to hold the band together. All the great bands had great drummers—Basie had Jo Jones; Tommy Dorsey had Buddy Rich; Woody had Dave Tough.

“And then a good lead trumpet player. These are the guys who sort of run the band. They lay the time down for the band.

“We have a very great brass section. Four of the trumpets play lead—Ray Triscari, Al Porcino, Frank Higgins and Stu Williamson. And Conte Candoli, along with Dizzy Gillespie, is the best big-band jazz trumpet player.

“Three of the trombones play lead. Frank Rosolino, Vern Friley and Bob Edmondson keep everything going.”

Of the lead alto man, Joe Maini, Gibbs cannot sing enough praises: “Point to Joe—for anything—and he can do it beautifully. Jazz or lead, doesn’t matter.”

Rounding out the sax section are tenor men Bill Perkins and Richie Kamuca; Charlie Kennedy, second and jazz alto saxophone, and Jack Nimitz, baritone saxophone.

In the rhythm section are pianist Pat Moran, for several years leader of her own quartet; bassist Buddy Clark, who with drummer Lewis toured with the Gerry Mulligan big band during the last two years; and Lewis, who, according to Gibbs, “holds any band together.”

Whenever its necessary to substitute because of illness or other Acts of God, Lou Levy generally gets the call for the piano chair; Frank Capp or Larry Bunker on drums (and the Bunker-Gibbs vibes duets on occasion have been memorable); Johnny Audino, Jack Sheldon, or Ray Linn in the trumpet section; and Bil Holman, Teddy Edwards or Bud Shank in the saxophones.

Why, in Gibbs’ opinion, did the jazz critics vote for the band that is (a) non-full-time and (b) whose appeal outside Los Angeles-Hollywood lies wholly within the grooves of long-play records?

“On the strength of those records, I would think,” he said. Then he added, “If they liked the band on the albums, they would like it 20 times better if they heard it in person.”

DB