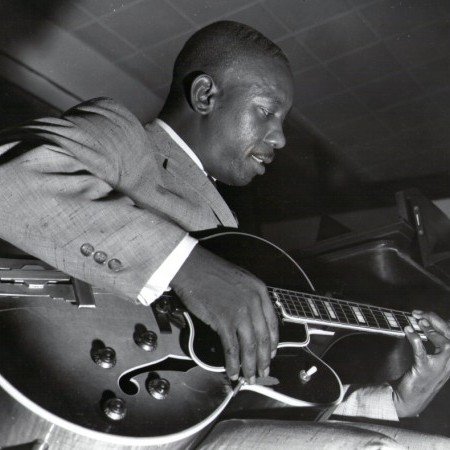

Wes Montgomery plays at the Essex House Hotel in Indianapolis in 1959.

(Photo: ©Duncan Schiedt/Courtesy of Resonance Records)The exact dates the mysterious tapes rolled to capture Wes Montgomery and his group are unknown — it was probably sometime in 1957 or 1958. The three settings of the recordings are also unclear. Some were recorded in an unidentified studio, and others in a club. The tapes were most likely made in Montgomery’s hometown, Indianapolis. Why they were recorded (and what happened to them in the decades that followed) remains open to conjecture. But one thing is certain: Montgomery offers a sound on these recordings that is unmistakably his own.

Now released as Echoes Of Indiana Avenue (Resonance), the recordings show the guitarist at a time when he was making a pivotal transition. Montgomery already had developed a distinctive approach to the guitar, shortly before record labels began calling. The disc also offers a compelling snapshot of a still under-appreciated jazz scene in a city that was removed from what were then the major musical hubs. Some critics have claimed that because Montgomery was away from the pressures, and influences, of the music industry of the late 1950s, he was free to experiment. Indianapolis offered a strong musical community, which included his brothers — pianist Buddy and bassist Monk — alongside such empathetic colleagues as pianist/organist Melvin Rhyne, bassist Mingo Jones and drummer Paul Parker, all of whom are on the tapes that became Echoes.

In the late ’50s, Indianapolis had its share of challenges and obstacles. Decades later, so does the story of how this album came into being. Echoes (available as a CD or double-LP) sheds important, new light on Montgomery, who was voted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1968, the same year that he died.

Indianapolis, 1957–’58

Montgomery could have chosen from a number of different routes when he returned to Indianapolis in 1950. He had just come off of a two-year stint touring with vibraphonist Lionel Hampton in a big band that also included bassist Charles Mingus and trumpeter Fats Navarro. But the notably clean-living guitarist also had a wife and children to support. As he told Bill Quinn in the June 27, 1968, issue of DownBeat, “What I wanted to do didn’t matter as much as what I had to do.” So, he would wake up early to begin an eight-hour shift at a radio parts factory starting at 7 a.m., which did not prevent him from working on the Indianapolis club scene at night, at venues such as the Hub-Bub, Turf Bar and Missile Room.

While Montgomery was regularly holding multiple jobs during these 14- and 16-hour workdays, he was being noticed far from Indianapolis. At the end of 1957, he recorded with Buddy and Monk — and a young home-town trumpeter named Freddie Hubbard — for sessions that would be released the following year as Fingerpickin’ (Pacific Jazz). The record didn’t make a huge dent in the jazz marketplace, but it could have contributed to the interest that musicians like saxophonist Cannonball Adderley and composer Gunther Schuller began taking not just in the guitarist, but his Midwestern city, too. They had a lot to observe there, according to the musicians who worked with the Montgomery brothers at its Indiana Avenue clubs.

Jones was one of the musicians who had been active on that street since he left the Army, where he doubled on trumpet in military bands and served in the Korean War. He recalled that the Indianapolis club scene also emphasized a strong sense of discipline.

“Indiana Avenue had clubs wall to wall, and they were not just clubs — they were nice, clean clubs,” Jones said. “The musicians who came there had to be dressed properly, and they had to play well. The clubs didn’t accept no half-job; you had to be on time. Most club owners wanted to make money, and you can’t make money if you’re not organized. These guys who came on the avenue had the chance to learn how to be great musicians. They were also helping younger musicians to study and learn what being a musician was all about.”

Those thriving clubs, such as George’s Bar, Henri’s, Mr. B’s and the 16th Street Tavern, were located in the city’s predominantly African American neighborhoods. Echoes Of Indiana Avenue commemorates this time and place through the photographs and essays in its liner notes. Educator/bandleader David Baker has said that there were around 20 small theaters, bars, bistros and other venues where jazz flourished at the time. He made the rounds there as a young trombonist, trying to soak up as much as he could at jam sessions that the Montgomery brothers and their contemporaries were running.

“As a player in high school, I had to draw a mustache on with a pencil so I could get into the clubs,” Baker said. “And I’d wear my Dizzy Gillespie glasses, which had no glass in them. High-schoolers like me would wait for Tuesday nights so we could go from club A to club B to club C, and I believe we were playing the same solos at the last one that we did at the first one. But since you couldn’t be in two places at one time, we had some kind of anonymity. When you got these places to play, and you’re not going to make any money anyway, this is the time to hone your skills.”

This supportive community thrived even though racial discrimination was about as pronounced in Indiana as it was in Southern states during the era just before the civil rights movement. After mentioning this history, Baker added, “Let’s just say that segregation was less flagrant among musicians than it was in the town at large.” He also noted that there was an unintended, positive consequence to the restrictive codes that kept Indianapolis’ Crispus Attucks High School an all-black institution.

“When you place all these people who are extremely talented in one place, the likelihood of you coming out with a gold piece now and then is more likely than if we were dispersed,” Baker said.

Talented high school students like Baker and Hubbard also had the Montgomery brothers as after-hours teachers. Sometimes their lessons amounted to letting the protégés know what they had to study for themselves.

“Buddy was a fearsome piano player — he taught himself and it never occurred to him that there were things that he couldn’t do,” Baker said. “He had Bud Powell under control the way he played. But there were some other circumstances. Monk was a little more adventuresome. I remember he was a mentor. We were playing in midtown Indianapolis, which was unusual because of the segregation. We were playing ‘Darn That Dream’ and I was playing piano, or I should say playing at piano, and we came to the second chord, which I would miss, and Monk said, ‘No, that’s a B-flat.’ I said, ‘That’s what I’m playing.’ He wouldn’t tell me the quality of the chord — that it was a B-flat minor or major. Monk was also one of those people who was very aware of his physical prowess. If anything happened, he could take care of it. The most deadly words you could hear as a novice were Wes saying to you, ‘What are the changes?’ Because then he’d say, ‘You’ll hear it,’ which meant, ‘Go home.’”

Toward seasoned musicians, Wes Montgomery in particular was remembered for being especially generous. In the late ‘50s, Jones was playing at Andre’s when bassist Leroy Vinnegar recommended him to the guitarist.

“Although Wes had great talent, he was a regular, loving guy, and he would always help you,” Jones said. “When guitar players came to town, he’d go up to them and he’d introduce himself. He was just that type of person. Even after he had got famous, he’d come to town and stop by my apartment. Wes would come by and talk about his experience on the road, and say he’d wished we’d all been together. But the way it happened, everything went smooth.”