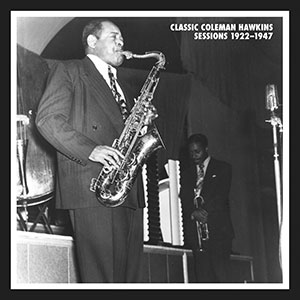

Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922-1947

(8 CDs)

The saxophone was patented more than a half century before jazz developed but their affinity for each other might be nearly perfect. Potent, like the brass instruments whose ringing bell it shares, yet, sensitive as a clarinet thanks to the way its cane reed responds to changing embouchure, tonguing, breath, and attack, the saxophone can do everything a jazz instrument needs to do.

And no one knew it until Coleman Hawkins showed us how.

The man whose innovations elevated saxophone to its rightful place in jazz is finally getting the retrospective he deserves, in a manner that only Mosaic can deliver. Thanks to our "limited edition" policy and the fact that rights to recordings on a host of labels have come to be owned by Sony Music, we are able to present a collection that crosses original label boundaries to define what was truly the best. We're calling it "Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922-1947" and it covers Hawkins as a leader and as a sideman.

Our research has corrected many discrepancies in previous discographies. In an effort to be complete within the scope of the project, we have gone back to the best source available for every one of these recordings, be those original metal masters, test pressings, 78s, and in a couple of instances where no other source can be found, commercial CDs. Liner notes are by Loren Schoenberg, a Grammy-winner for his notes to our Woody Herman set. The box also includes a host of rare photographs from Hawkins' career.

We took loving care with this project, believing it may be the last time some of it will ever be available. Please don't miss out on this one-in-a-lifetime opportunity to own music you will listen to forever.REVIEW

DownBeat / October 2012

★★★★★

Hawkins Lifted Whole Bandstands

by Kevin Whitehead

The new collection of the saxophone master, Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922–1947 (Mosaic 251; 66:28/66:42/66:01/ 70:40/78:04/78:20/73:01/78:16), culled from Sony’s now mega-massive vaults and public-domain recordings, has the sweep of a long novel. We meet Hawkins slap-tonguing behind blues queen Mamie Smith, and leave him a quarter century later, standing toe to toe with young boppers Fats Navarro and Max Roach. Some crucial stuff gets left out; crucially, there’s nothing from his too-neglected five years in Europe. But what’s here is an abundance that risks being too much: Hawkins progressing inch by inch. Records never tell the whole story, but 15 dozen tracks (including a smattering of previously unissued tunes and takes, some in rough condition) reveal the grand arc of a career.

Even in slap-tongue days he had a sound, his wavering tone and tremolo kin to Sidney Bechet’s (and Albert Ayler’s). Hawkins’ rhythmic concept began evolving when Louis Armstrong passed through Fletcher Henderson’s early orchestra, whose familiar and obscure recordings constitute most of the set’s first half. By 1926’s “The Stampede,” Hawkins’ mature voice is emerging: the declamatory tenor saxophone tone; the peerless embroidering of chord progressions with elegant improvised lines; the headlong momentum sometimes a little short on rhythmic variety. Some saxophonists swung harder, but Hawkins knew other ways to thrill the heart.

“One Hour” from 1929 laid out the rhapsodic approach to ballads that would culminate a decade later in “Body And Soul.” You can hear that performance’s exquisite poise and invention coming, in any number of early ’30s ballads.

Henderson’s big band helped inspire the swing era, but was in something of a slump before the galvanizing 1933 date with Hawkins’ whole-tone-happy “Queer Notions” and three other tunes so fresh, Sun Ra would revive them all 50 years later. Hawkins’ free way with tricky harmony and his authoritative, voluptuous sound ripened in tandem. The lightly chugging mid-’30s Henderson beat was a locomotive heard in the distance, with Hawkins leaping over the tops of the box cars, moving ever forward.

Then come the expatriate years the anthology skips over, though they get their due in Loren Schoenberg’s epic annotations, which pinpoint specific aspects of Hawkins’ style that inspired select followers. “Body And Soul” announced his homecoming, but its assurance and carefully modulated escalations in pitch, dynamics and intensity suggest what Europe did for him. He was now even more self-reliant, more capable of lifting the whole bandstand, more confident as an artist. Even surrounded by so much good and great Hawkins, “Body And Soul” remains disarming.

Later, when producers asked for another ballad like it, he’d reply, “I’ve made hundreds of them.” We hear more than a few from the years that follow, where other horns fall in softly behind him, the rhythm section padding along in 4/4.

A 1943 “Sweet Lorraine” shows his uncanny ability to suggest a melody he largely avoids. “Lover Come Back to Me” from the week before confirmed Hawkins’ appetite for tasting every passing chord, even as his tone became more gorgeous. On that session—with Roach on drums and bassist Oscar Pettiford thinking like a horn player, gasping for breath between phrases—Hawkins plays a masterful “Blues Changes” where he keeps changing keys between choruses. (His blues are relatively few, and generally underrated.)

Hawkins’ early ’40s big band was a short-lived fiasco, but in a way that decade was his time. “Hawk’s Variations” circa 1945, first of several recorded opuses for solo tenor, looks to the postmodern future, even as its overtone-rich opulence echoes his early cello training. A stiff band had never held him back, but now he hired young boppers whose offbeat accents goosed his rhythms, and who could follow his altered chords and harmonic abstractions.

The ’40s settings also take in various Esquire and Metronome all-star dates, one with vocals by a very tasteful Frank Sinatra, June Christy and Nat Cole. Hawkins as ever is in the thick of it, talking on all comers. DB