Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

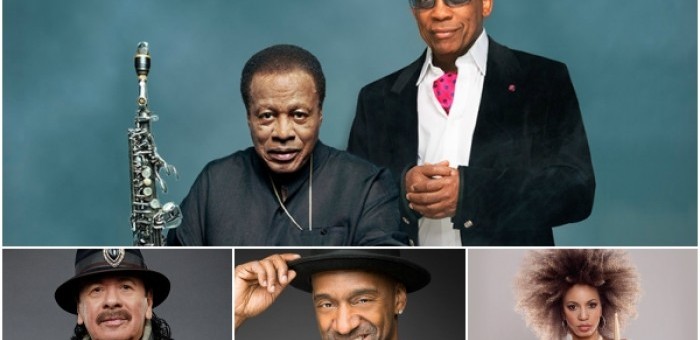

Top: Wayne Shorter (left) and Herbie Hancock. Bottom: Carlos Santana (left), Marcus Miller and Cindy Blackman Santana.

(Photo: Courtesy hollywoodbowl.com)Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter are regular visitors to the Hollywood Bowl, one of the world’s largest venues in which jazz appears on a periodic basis. Hancock and Shorter are, after all, the premier jazz legends calling Los Angeles home, and the commute to this space from their abodes just over the hill makes it almost like a neighborhood gig.

But this summer’s Hancock-Shorter encounter at the Bowl was something with a bigger, broader buzz of attraction: an all-star, mixed-genre bag with rock icon Carlos Santana drawing in an unusually epic crowd, nearly filling the 17,000-seat Bowl.

Grandly dubbed “Mega Nova”—a nod to the 1969 Shorter album Super Nova—the evening’s special ensemble also included heroic genre-crossing bassist Marcus Miller, the ever-flexible, powerhouse drummer Cindy Blackman Santana (Carlos’ wife and a fine bandleader in her own right), and the Santana group percussionist Karl Perazzo.

The concert opened the warm, retro-soul sounds of Booker T and his Stax Revue. Apart from the Booker T of the instrumentals “Green Onions” and “Soul-Limbo,” the band, fortified with fine horn players and a trio of vocalists, doled out favorites of the classic Stax repertoire—“Knock On Wood,” “Mr. Big Stuff,” “Try A Little Tenderness” and the lesser-known but nonetheless moving version of the Sam and Dave hit “When Something Is Wrong.”

If Booker T’s set was a crisp hit-parade of yesteryear, the “Mega Nova” experience was something else entirely: a sprawling panorama of fleeting references to songs from the artists onstage and beyond, a cubist account of 20th-century music—mostly jazz, but not exclusively.

Santana is obviously a great lover and supporter of jazz, but isn’t a jazz musician per se, and his solos were largely rooted in his fluent blues-based vocabulary and signature searing long tones.

At times during this rambling musical journey, one longed for more harmonic variations and chord changes, and for more expansive input from the sometimes-too circumspect Shorter, but this program steered toward a modal middle ground, perhaps to accommodate Santana’s harmonic comfort zone.

Operating as something of a benevolent, open-to-suggestion musical director, the guitarist signaled shifts of material of the melting medley sort—sometimes jarring, sometimes with the surprise of serendipitous delight.

Halfway through the set, the theme to Spartacus rang out in the roving musical mix of ghostly snippets, and later, the familiar four-note riff from “A Love Supreme” landed on the Bowl stage with Santana’s distorted power chords attached.

During the show, Santana also snuck in brief quotes from the wide world of music, from the opening theme of Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring in the first section of the concert to Carole King’s “I Feel The Earth Move” in the midst of the seminal Santana hit “Oye Como Va,” and a pinch of “My Favorite Things” in “Afro Blue.”

With this particular aggregate of musicians, the oeuvre of Miles Davis was easily—and validly—tapped into. Of course, Hancock and Shorter were key figures in the great mid-’60s acoustic Davis band, and Miller was a central creative ally—as producer, player, facilitator—in the final, ’80s chapter of Davis’ life.

Throughout the night, echoes of Davis’ multi-chaptered career appeared like a subplot. Shorter’s “Footprints” and “Freedom Jazz Dance” (with only Miller navigating the spidery Eddie Harris melody line)—from the 1967 album Miles Smiles, were flown into the set, as were riffs and passages from Jack Johnson, and the ’80s business of “Time After Time” (à la Cyndi Lauper, not Sinatra), with Shorter playing the melody from a Davis phase he wasn’t originally a part of, but easily fits into.

If Shorter’s presence was more minimal than some would have liked—in keeping with his retiring, cryptic nature in a group, especially a loud one—he made short statements count. Deeper into the set, Hancock embarked on a few memorable and inventive, harmonically rangy solos, on Rhodes and grand piano, giving us something more cerebral to chew on.

But this was the Bowl, where the party impulse is often brewing beneath any serious musical offerings. Capping off the 85-minute set, Santana and company eased into the easy-to-love, groove-lined terrain of Hancock’s “Watermelon Man” and Santana’s “Oye Como Va.” And then—what else?—the “Star Spangled Banner,” respectfully played, but ending in an abstract of sound, out of respect for Jimi Hendrix.

Hendrix, Francis Scott Key, the power trio at hand, Miles, Coltrane: These were but a few of the musical things flying around the dream continuum in Hollywood on this night.

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Larry Goldings’ versatility keeps him in high demand as a leader, collaborator and sideman.

Feb 21, 2024 10:45 AM

Are you having any fun? Larry Goldings certainly is. Consider just two recent examples:

Scene 1: “If anyone had…