Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

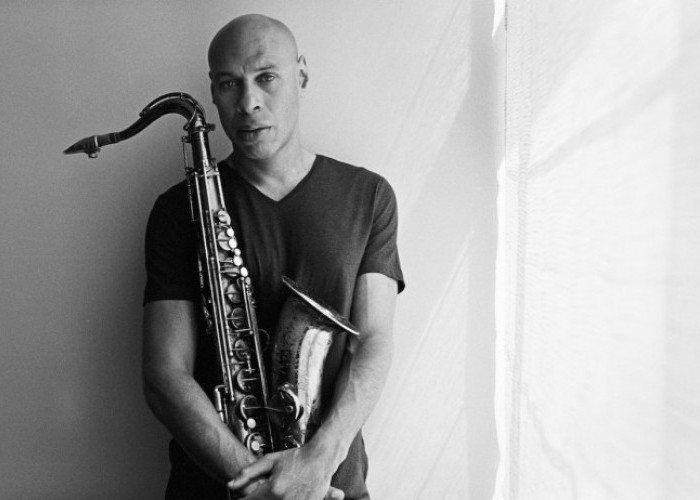

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

Joshua Redman’s current quartet first convened in 1998.

(Photo: Michael Wilson)What’s really weird for me is what constitutes canon these days. For a long time, people came up to you ... and referred to recordings that you made. And you had some sort of sense of “I released that,” or “I had some involvement in someone else’s record.”

But now, it might be some random, janky bootleg that’s up on YouTube taken at any gig by anyone with a cell phone. Or it might be from some TV show in Poland or Germany that someone just captured and threw up there. Those are now sometimes the source material more than the [official] recordings themselves.

I really get that a lot when I meet musicians under the age of, say, 25. I’ll be in a situation where someone will ask me a question about one of those performances or videos that I have no recollection of. And they’re astounded that I don’t remember it. Because for them, that’s the one that got passed around and shared. Or it’s the one that reached the top of the algorithm, and it’s got all the views.

It’s the new reality, and I’ve accepted it. But it was a little disconcerting at first. And maybe it’s presumptuous for us, as artists, to ever think that we could or should have some sort of control over what people get to hear—or what’s most heard, you know?

I remember hearing that when you were on tour back in the ’90s, you would survive on just a couple of hours of sleep per night.

That was a real active time, and I was in my twenties. And there were a lot of gigs. I remember one year, I think it was ’95 or maybe ’96. I was living in New York, and I never spent a full week, a full seven days, at home. I probably did 300 gigs that year.

I didn’t enjoy getting two or three hours of sleep a night. But I could handle it in a way, maybe, that I can’t handle now. You’re just more resilient when you’re young, and I had less responsibility in life. I didn’t have a family.

That was a very different time. There were more activities going around, more stuff to do outside of the gig. We used to do in-store performances. That was a big thing.

And there was a time when I was willing to say “yes” to a lot of things. I mean, I’m happy to do this interview. But generally, these days, I’m just, like, “Man, I don’t have anything to say!” [laughs] Back then, maybe, I did have something to say with my mouth, but didn’t have that much to say with my horn. Now, I feel like I’ve got something to say with my horn, and that’s about all I have to say.

But I was lucky, in a way, to be around back then: It helped create a career for me. And it’s very different now.

When I heard that Roy Hargrove had died, you were one of the first artists I thought about. Was he one of the first of your peers to pass away?

That was shocking for all of us. It really hit home on that kind of personal, generational level. He was 49, and I was still 49.

And when you say “peer,” I’m not saying that I’m at his level. It’s more that we were age peers. I consider myself a late bloomer, because when I came to New York I was, like, “Roy Hargrove! Christian McBride! Greg Hutchinson! Brad Mehldau!” These were some of my idols, because I’d just come from college. And they were already on the scene, doing it.

I got to play with Roy early on. I got to do some guest appearances with his band. And probably the first time I played with Greg Hutchinson was in Roy Hargrove’s band.

Roy was one of my favorite musicians. He was so inspiring. The word “natural” is bandied about a lot, but he was just a true natural. He worked really hard, though, and was very serious about music. He had a deep, deep understanding and really owned his craft.

The soulfulness and spirit and just his gift for melody and rhythm and the feeling in his playing was so righteous, so raw and so, so true. He was one of those musicians where I would hear him and be like, “Well, I’ll never have that. But I want to get as close to that as possible.”

As far as musicians from our generation, [bassist] Dwayne Burno [1970–2013], he’s the other one that comes to mind. I actually knew Dwayne fairly well, because I played with him a lot when I was in Boston. There probably have been a few others that aren’t coming to mind.

They were both so shockingly young. But you get to this part of life, middle age, where you start to lose friends and loved ones. And none of us know what’s next. So, we just have to make the best music we can and live the best life we can and come what may. DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Larry Goldings’ versatility keeps him in high demand as a leader, collaborator and sideman.

Feb 21, 2024 10:45 AM

Are you having any fun? Larry Goldings certainly is. Consider just two recent examples:

Scene 1: “If anyone had…