Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

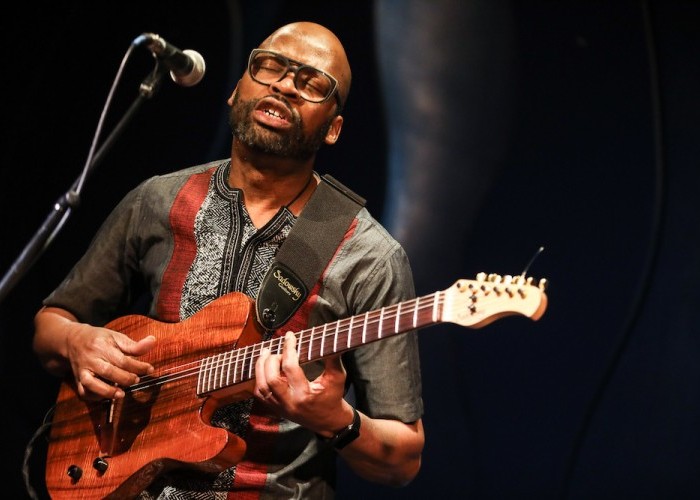

Lionel Loueke incorporates styles and sounds from other instruments into his guitar playing.

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)Loueke ascribes some of that rhythmic facility to his preference for playing fingerstyle. “I don’t play with a pick,” he explained. “My approach is closer to the classical guitar technique, so on my right hand I deal with four fingers. That gives me more freedom to combine different lines and play polyrhythms. I want to get something close to the [sound of a] piano, but not exactly, because I want to have the freedom of doing whatever I’m hearing—if I can.”

Loueke appreciates Sadin’s ear for additional color, as well as his ability to bring classical instrumental technique to the arrangements—something the guitarist describes as “Bob Sadin’s magic touch.”

One example is the oboe-like introduction to “Gbêdtemin,” which is based on a phrase from Debussy’s Gigues. Sadin had come up with that on one of his keyboards, and played it for Loueke. “Some of the songs—‘Gbêdtemin,’ ‘Vi Gnin,’ ‘Hope’—those three have some classical movement, harmonically speaking,” the guitarist said. “So, when he proposed that to me, I was like, ‘Yes, please. Can we use that?’”

Sadin also brought in classical clarinetist Patrick Messina and cellist Vincent Ségal to flesh out the chamber-style orchestration of “Hope.” But not all the string playing came from the classical realm. Violinist Mark Feldman had played with Loueke for a few concerts in Savannah, Georgia. And when Sadin was trying to come up with the right voices to flesh out the song “Kába,” Feldman came to mind.

“But I needed to get Mark—who’s so wonderful—really into Lionel’s world,” Sadin said. Rather than merely have the violinist add an overdub, he decided to have Feldman and Loueke sit down and play together awhile in the studio. It was an idea Loueke heartily endorsed.

“We don’t have many violin players who can improvise,” Loueke said. “Most of the time, when you hear a violin in jazz, it’s Stéphane Grappelli or someone like that. But Mark is a different cat. That song he played on, ‘Kába,’ it was just the two of us in the studio, and we played the same song for—I don’t know, an hour or 45 minutes. We told the engineer, ‘Let it roll,’ and we just played. That, for me, is where the real magic happens, because the whole thing bypasses cognition. You’re just following some great tone. It’s magical.”

Sadin was so pleased with what the two had played that he almost didn’t bother asking Feldman to have a go at the version of “Kába” Loueke previously had laid down. “I thought, ‘You know, I don’t even think I need him on the basic track.’ And Lionel says, ‘Well, let’s let Mark do it once, anyway.’ I’m not going to say no,” Sadin recalled. “So, he’s playing the version which had Lionel already playing parts underneath, but now he knew Lionel’s moves so well that in one take there was nothing to say. Done.”

“Kába” is the Fon word for “sky,” and the lyrics Loueke sings describe being energized and uplifted by gazing at the vastness of the sky. There’s an apt spaciousness to the music, which slowly builds in intensity as the different voices join in. In addition to Feldman’s violin and Loueke’s voice, there’s Palladino’s lean, melodic bass line, which locks nicely with the gently thrumming percussion of Christi Joza Orisha and Cyro Baptista. Dramane Dembélé adds breathy interjections on a Malian peul flute, and Sadin’s soundscapes add textures via synthesized oboe and string voices.

But the most striking aspect, instrumentally, about the track is the bright, brittle guitar lines Loueke sprinkles throughout, adding a sound that’s closer to the West African kora than to any standard guitar sound. “That’s something I’ve been working on for years,” Loueke said. “I’m from Benin, where we don’t have any history of the kora as an instrument. But I grew up listening to a lot of kora players, and I always wanted to play the kora. But it’s like the violin: It’s not the type of instrument you start to play when you’re old. You start when you’re young, and then you grow up with it.

“I’ve been working a lot on zooming in on different African instruments—doing transcribing, checking the tuning—to see how I can bring that back to the guitar. I made an application called GuitAfrica, which involves different African instruments on the guitar.”

GuitAfrica is an iOS app that features pieces (written and played by Loueke) that typify a quintessential musical style from 22 different countries. Each style is identified, with a page offering notes on the music’s style and origins, typical instruments and a short list of significant performers of the style. Loueke also includes notation—not just the overall score, but individual guitar parts with tablature. To make it easier for users to play along, the interface allows for looping, changing the playback speed, changing the pitch and isolating audio tracks. Overall, the app provides a practical, accessible education in African music.

“I just composed music for each of those countries, using the strongest rhythm,” Loueke said. “By doing that, I learned so much about different instruments—the kora, the guimbri. All that work, it comes out when I play today, because it’s somewhere there with me.”

So, how did he get his guitar to sound so much like a kora? “I play a lot with the harmonics on the instrument,” he said. “Also, I have a mute technique which is, I think, a typical African approach. Where I grew up, many people mute their strings when they play.”

On some songs, he put paper on the strings to get a sort of resonant muting. “It’s a simple way to have a sound close to a kalimba, a vibrating sound,” he said. “When it comes to the [guitar] sound, I’ve been working a lot on what I’m hearing and what I’m trying to make on the guitar.”

“Dark Lightning” contains the most jaw-dropping bit of electric playing on the album. The track was recorded with only Loueke’s voice and guitar, but it features a sonic wave that resembles an entire orchestra of electric guitars. All the layered growls and whines were not the result of overdubbing, but of Loueke’s mastery of digital delay and, particularly, the Kemper Profiler digital guitar amp.

“That was one take,” Sadin said of the guitar track. “There weren’t overdubs on that. Lionel has a very evolved relationship with his digital processor, so this is coming all at once. All those colors, all those guitar pads, that’s all from this one device.”

Since finishing the album, Loueke has played some shows in support of his own work, but his versatility makes him an in-demand collaborator. In 2017, he toured as a member of The Chick Corea & Steve Gadd Band. He recently did a European tour with Dave Holland’s Aziza, and in January he’ll perform with Jeff Ballard in Germany. In October, Loueke played with Herbie Hancock’s band in Kuwait, and he’ll go back on the road with the keyboardist this year.

“I’m lucky, because I’ve got lots of offers to do different things,” Loueke said. “My approach to music is open, so I’m not locking myself to one style. I can go [perform] with Angélique Kidjo, play something, record something, and then Kenny Barron or Kenny Werner. I like to jump from one project to another, because I learn more doing that. The most important thing for me is to bring something to help the music. And to be myself.

“Wherever good music is taking me, I’m going.” DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…