Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

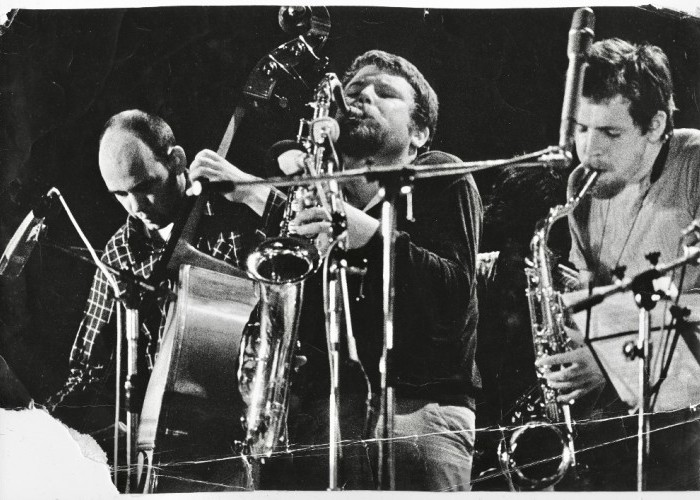

Bassist Buschi Niebergall (left), saxophonist Peter Brötzmann and saxophonist Willem Breuker, shown here in 1970, perform on Machine Gun, which hits its 50th anniversary this year.

(Photo: Keira Brötzmann)The marathon, lung-bursting howl of Peter Brötzmann’s Machine Gun, which the saxophonist self-released on his BRÖ imprint 50 years ago, captured the anxiety of a generation grappling with the Vietnam War and civil unrest. The emotional and political complexity it was born from still resonates today.

Before he entered the world of music, Brötzmann was studying to be a painter in Western Germany and was associated with Fluxus, a radical art movement influenced by John Cage and informed by an anti-commercial sentiment.

“[With Fluxus], I was involved with various creative people—playwrights, actors, dancers and so forth,” he recalled. “All we talked about was how to get rid of the old structures.”

A perennial jazz fan, the stage provided Brötzmann with a more suitable home for his artistic vision than a pristine canvas. From the outset, as captured on his 1967 debut For Adolphe Sax, Brötzmann’s violent and experimental approach was fully on display.

“On the continent, it was hard-bop time. Art Blakey was always touring Europe. But so were Charles Mingus and Eric Dolphy. That was something for our ears,” Brötzmann said.

After gigging for years, two landmark performances with his trio at the Frankfurt Jazz Festival landed Brötzmann the opportunity to put a bigger band together. Alongside the drummer and bassist from his original trio, he brought together players already firmly established within the German and Dutch avant-garde, including Han Bennink and Willem Breuker, of the Instant Composers Pool. Brötzmann also recruited rising British reedist Evan Parker.

It’s easy to explain the album’s singular energy as Brötzmann and company harness the era’s ambition of plotting a new path forward. But in the bandleader’s mind, “There is no contradiction between creation and destruction. I never thought music was a healing force of the universe. I didn’t agree with Mr. [Albert] Ayler. But we wanted to change things; we needed a new start. In Germany, we all grew up with the same thing: ‘Never again.’ But in the government, all the same old Nazis were still there. We were angry. We wanted to do something.”

Machine Gun, its name derived in part from Don Cherry’s description of Brötzmann’s distinctive sound, found a new start by returning to the very roots of jazz. Despite the album’s iconoclastic reputation, Brötzmann conceived a relatively simple framework for it.

“I got some paper and wrote and drew some things. It’s a very conventional, simply structured piece,” said the saxophonist, who has a handful of August tour dates set in California with avant-guitarist Keiji Haino. “It’s a Charles Ives thing: solo, solo background, solo.”

The assembled group’s lack of familiarity with one another necessitated the approach.

“We were all quite new to each other. Evan Parker could play ‘Giant Steps,’ which was very impressive. But he heard what I was playing and was surprised by the sound I could make,” Brötzmann said. “I had to find a way to organize the most freedom possible, but to give some structure to hold onto.”

Machine Gun’s 45-second intro forms one of jazz’s most distinctive mission statements. Parker weaves around the horn section’s staccato blasts, before Bennink’s drums blast a nervy military march alongside Peter Kowald’s wildly rumbling bass. The brutality of the album’s remaining 36 minutes exceeds the number of commonly recognized synonyms for “violent.”

In part, the octet achieved its sound by marshaling the expressive possibilities represented by the blues. While Cage and the European avant-garde made Machine Gun possible, its content owes more to the hot jazz of Louis Armstrong than the obscure theory emanating from academia at the time. Ultimately, Machine Gun is the blues for a continent ravaged by a century of internecine warfare, unfathomable crimes against humanity and an uncertain future.

Like its predecessors in that tradition, the album, which is being reissued by the Trost imprint, sought to reform a broken system by expressing profound and intangible truths while living within it.

“We can make changes to the system. We can reach single souls. We can open up their horizons,” Brötzmann said his hopes for what Machine Gun could do. “But the vision was bigger than the reality. Reality and capitalism are stronger than anything.”

Machine Gun’s legacy continues not just as a result of its considerable accomplishments, but because of the volatile period it reflects and refracts, a time when people waited impatiently for an artistic gesture powerful enough to change everything and prevent history from repeating itself. DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Larry Goldings’ versatility keeps him in high demand as a leader, collaborator and sideman.

Feb 21, 2024 10:45 AM

Are you having any fun? Larry Goldings certainly is. Consider just two recent examples:

Scene 1: “If anyone had…