Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

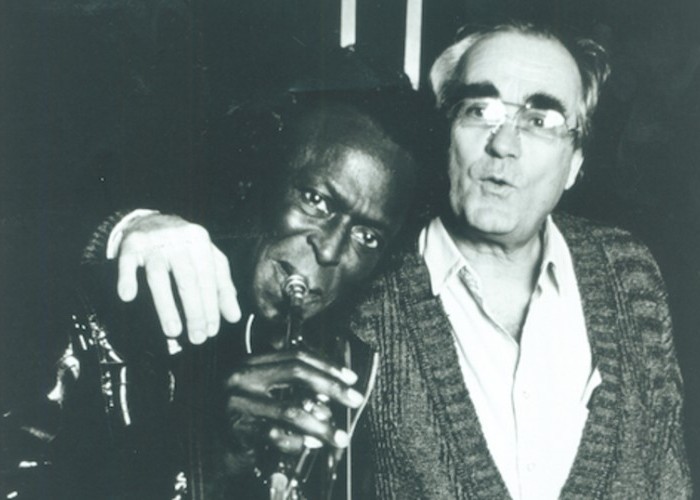

Miles Davis (left) and Michel Legrand in a publicity photo for the soundtrack to the 1991 film Dingo

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)“The first jazz album I made was with Miles, and the last album he made was with me,” said Michel Legrand during a recent interview. The acclaimed composer/pianist/singer was referring to his 1958 album Legrand Jazz, and Miles Davis’ 1991 album, Dingo, the soundtrack he and the trumpeter made for the film of the same name shortly before Davis died on Sept. 28 of that year.

Legrand was in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in May to receive an honorary doctorate from Western Michigan University as part of his first visit to the Irving S. Gilmore International Keyboard Festival.

The honor from WMU is the latest is a long list of accolades. Among Legrand’s five Grammy victories are wins in 1971–’72 in the category Best Instrumental Composition for writing the themes to the TV movie Brian’s Song and the film Summer of ’42. He took home Academy Awards for the music he composed for the films The Thomas Crown Affair, Summer of ’42 and Yentl.

DownBeat caught up with Legrand in Kalamazoo.

What was the origin of Legrand Jazz?

The Americans, they wanted me to do an album about Paris, with all the orchestration. They asked, “Would you be interested?” Unfortunately, there was no money, no royalties. Two hundred dollars, and that’s it. I said, “Fine, I don’t care.” It would be a good try for me. So I made the album [I Love Paris, 1954], and it sold eight million copies.

In a year or two, they have a big party, and Columbia says to me, “We would like to give you a present. Tell us [the kind of] album you want to make, and we’ll pay for it, and you’ll do it.” So I said, “I want to do a jazz album—with Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and I named all the jazz musicians on the album. And they said, “Let’s do it.”

So, in 1958, I went to New York with my orchestration, Ben Webster, Herbie Mann, Jimmy Cleveland and all the others [including Ernie Royal, Phil Woods and Hank Jones].

So what happened next?

Miles wanted to talk to me before the session. He says, “Can you play for me?” So I played the orchestration on piano and he said, “Fine, OK, good.” All the musicians in New York had said [things like], “Be careful with Miles, because he’s such a character.” “He arrives at the session 15 minutes late, on purpose.” “Miles will open the door to the studio, and stand at the door and listen to the orchestra. If he likes it, he comes in, sits down, he has his trumpet. If he does not like it, he gets out of the studio, closes the door, and you never hear from him anymore.” And I thought, “Oh, my gosh!” I was 26 years old.

And that’s exactly what happened at the first session, with Miles and his group with John [Coltrane], Paul Chambers and Bill Evans. Miles opens the door, about 15 minutes late. He’s still at the door, and then, he gets in, closes the door, settles down, opens his case, and starts to play. And after that first session, Miles came to me, and he said [imitating Davis’ raspy voice], “Michel, do you like the way I play?” I said, “Miles! I would never tell you how you play. I’m so happy you’re on my first jazz album. You’re a genius, and if there’s anything … you know, “Open the skies … .”

Tell us about making Dingo in 1981.

Miles could call me anytime, day or night. Miles calls me: “Michel, you need to bring your fucking ass to Los Angeles.” I said, “Miles, don’t worry. You want me, the next day I’ll take the train to Los Angeles.” He said, “Michel, there’s a film, and I want to do it with you.”

So, on the first day, I’m in the area. On the second day, we talk a lot. We go swimming. We drank a lot. It was a Saturday, and we were supposed to record the following Wednesday. So I said, “Miles, we’re supposed to compose it together. We should start to work.” He said, “Work! I don’t want to. Who gives a shit about the film?”

I told him, “If you don’t want to do it, OK. It’s good to relax—to really enjoy, talk about the music, have a beautiful vacation.”

But there was a phone conversation with someone from the studio; they were going to start shooting soon, and they need the playback to help [them] make the film.

I tell Miles, “We said we were going to do it. This isn’t about you, or your Grammys.” He said, “Fuck off! Who gives a shit about this, man?” I recall [a musician had] said, “The way Miles works is this: He goes into the studio with his musicians and—Miles is the laziest man on earth—comes afterwards and puts his trumpet up and overdubs.”

So, I see he’s expecting me to do the same. So, I said, “Miles, I have an idea. I’ll go to my hotel now. I will write everything, the complete orchestration. I will record on Wednesday, all the charts. Come Thursday to the studio and take your trumpet and play.” He said, “Michel, I knew you were a genius.” I record all day Wednesday, and then the next day, Miles comes. I loved that man. So generous, so strong and very open at the same time.

Can we talk some more about 1958 and Legrand Jazz?

OK. When we finished the album in New York, Miles said, “I’m playing at the Newport Jazz Festival. Come with me.” I said, “Great, fine.” I remember I had a 16-millimeter camera. While we’re having dinner at the festival, in comes [festival founder/director] George Wein. He says, “Hey Miles, don’t forget that tomorrow, it’s a tribute to Duke Ellington.” And Miles says, “Forget it. I hate Duke’s music. I will never play his music.”

So then Wein said, “You have to play. It’s in your contract. If you don’t play, I’ll shoot you … And Miles said, “Screw you, George.”

[The next day] they all go up on stage, and they start to play. Miles, his trumpet is in his hand; he stands near the piano. He never blows his trumpet once, but he was on stage. The musicians play, but he never puts his trumpet to his lips.

So, Miles was very important in my life. Extremely important. DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…