Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

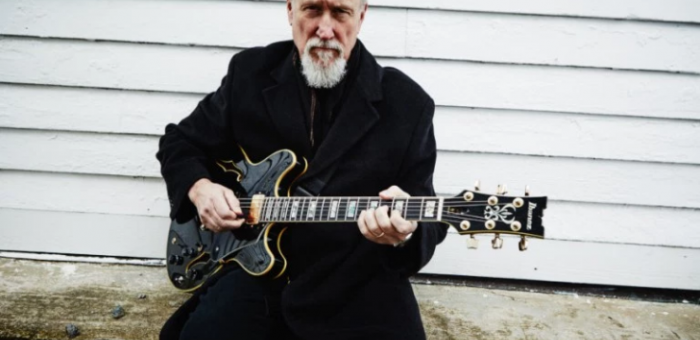

On John Scofield’s new album, Country For Old Men, the guitarist interprets classic country music tunes.

(Photo: Courtesy johnscofield.com)John Scofield is known for pushing genre boundaries with his guitar, and his most recent foray into musical hybridity is Country For Old Men (Impulse!/Verve), an album on which the six-string veteran wrangles classic country tunes.

The 12-track program reaches back to legends like Hank Williams (“I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”), George Jones (“Mr. Fool”) and Merle Haggard (“Mama Tried”). But don’t worry: While Scofield puts a little twang in his trusty Ibanez ax, he never loses his jazz identity.

The band—featuring pianist Larry Goldings, bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Bill Stewart—honors the vintage country winsomeness of these songs while refusing to be limited by it. Their hard-swinging jams allow Sco’s angular disposition to emerge vividly.

DownBeat spoke with Scofield as he and the band prepared for a weeklong appearance at The Blue Note in New York City.

So what prompted an album of country covers?

For a long time, I’ve thought it would be great to do a whole country album, and I had toyed with the idea of going to Nashville and playing with country guys. But then I thought, “You know, there’s a way to do what we did on this album, which is really blending jazz and country more, and to do it with some of the guys I play with, who are sympathetic to country music.”

I’ve had a trio with Bill Stewart and Steve Swallow for years, and Larry Goldings played in my band for a few years in the ’90s, so I really know how those guys play and I knew we could make jazz out of these songs.

You seem to have adopted the idiomatic twang of these country classics into your own sound. How did you get yourself and your band into a country state of mind for this album?

I just listened to country music, and listened specifically to songs I knew we wanted to play and I learned them. I knew them anyway, but just sat down and played the melodies on my guitar and really thought about performing them as single-note melodies.

And for the other guys, I sent them a little four-track demo that I made of my arrangements of the songs, where I had a drum track going and played bass and rhythm guitar. And I also sent them links to the original tunes so they could hear those, too. But I’m not sure how much of that they listened to [laughs]. Then we got together and recorded.

The band really captures the original authenticity of these melodies before departing into some burning jazz, yet the transition never seems forced or awkward.

I picked tunes where I could have them turn into jazz, so we could blow and swing on them, and I maybe changed the chords a little bit to make each song a real blowing vehicle. That was really important because I didn’t want to do just folk-country. I wanted to be able to make jazz out of it.

You’ve talked about coming up in the ’60s in the suburbs of New York, during the heyday of electric blues and folk. But when did country first catch your ear?

I listened to the radio all the time, so I was aware of all the country music hits, since childhood, really. “Ring Of Fire,” “Jolene” and “Mama Tried”—you just heard them on the radio. Country music was big.

Even though I wasn’t a country music freak, I appreciated the guitar work, and I’ve always loved Appalachian music and bluegrass and that deep country sound of George Jones and Hank Williams. I’m a fan of that, along with being a fan of a lot of different music.

I never tried to play country music before and never hung out with many country musicians, so I’m certainly not qualified to be a country player. But I wasn’t trying to do that on this album.

On the last track, you play this ultra-catchy vignette of Johnny Mercer’s “I’m An Old Cowhand” on ukulele. How did that happen?

I was in Honolulu, playing at a jazz club there, and they gave me that ukulele, and I’d never really played one before. But the first thing I played when I picked it up was “I’m An Old Cowhand” because I was still learning songs for this record. And I liked the way it came out on the ukulele, so I used that. It’s a four-string ukulele with My Dog Has Fleas [G-C-E-A] tuning.

Did recording these songs your own way, with your own arrangements, enhance your connection to them?

Well, I’ve played these melodies on tour now and I feel a real connection to the songs, and of course I love the artists who sang them. They sang these melodies that I’m interpreting on the guitar, which makes it somehow different, and that’s why I wanted to do it.

When we were recording, I felt an emotional bond with the music that was very strong, and I remember feeling surprised about that. And then when we’d take them into jazz, it didn’t feel fake; it just felt right.

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…