Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

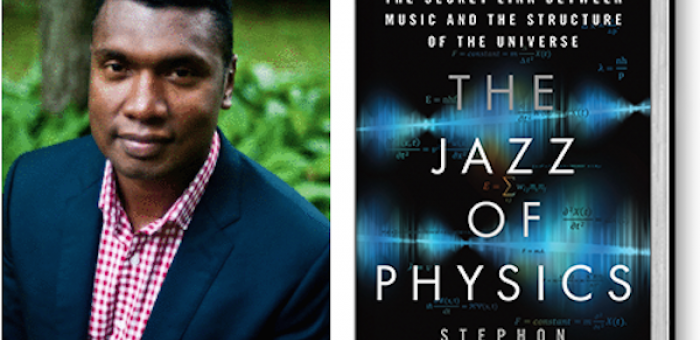

Stephon Alexander is the author of The Jazz of Physics: The Secret Link Between Music and the Structure of the Universe.

(Photo: Courtesy of the author)The idea of a musical universe—The Music of the Spheres—goes back a long way, from Pythagoras and the ancient Greeks to Newton, Kepler and Einstein.

In his groundbreaking book The Jazz of Physics: The Secret Link Between Music and the Structure of the Universe (Basic Books), the Trinidad-born, Bronx-raised theoretical physicist/tenor saxophonist Stephon Alexander—who recorded his first CD, Here Comes Now in 2014—shows how the improvisational nature of jazz is connected with cosmology and modern physics. He illustrates his points with colorful examples, ranging from the Big Bang to the eye of a galactic hurricane.

DownBeat spoke to Dr. Alexander from his home in Rhode Island, where he teaches at Brown University.

DownBeat: You’ve said that John Coltrane provided the eureka moment—the spark—that led you to write this book. How did that come about?

Stephon Alexander: The eureka moment for me was the first time I heard Giant Steps, which was in high school. Aside from it sounding really hip, I suspected that there was a hidden code … the same way a nuclear physics problem has a code. It sounded like it had a hidden code that would be amenable to the analysis of a physicist. Coltrane [sounded like he] knew the hidden laws of nature.

Sort of like Einstein.

Coltrane read everything about Einstein he could get his hands on. He told composer David Amram that he wanted to do with music the same thing Einstein did with physics, which was to find some sort of universal principle that basically brought all of the different branches of music together.

Like a unified theory of music?

Yes, absolutely!

In the book, you refer to a mandala [a type of symbol] that Coltrane made for Yusef Lateef that linked musical notes from different cultures in a unifying circle. What does that signify for you?

I argue that Coltrane’s diagram represented a unified theory of music. I made the case for why Coltrane’s mandala does reflect the same principles that Einstein talked about in his theory of space-time relativity. In that mandala, Coltrane shows the relationship and the connection between different, important scales in the Western musical system.

When scientists and philosophers point to an analogous relationship between music and physics and the cosmos, they often do so by referencing classical music. So how do jazz and jazz musicians provide an equally analogous connection to physics?

The jazz musician epitomizes the notion of creating spontaneously in real time on a given structure. Those structures can vary, and there are different forms in jazz that we have to improvise on. And in physics research, those skill sets are called upon when we’re working with each other, and when we’re talking about a new theory or a new idea, which also requires a kind of improvisational thinking. What jazz musicians do, physicists do the same thing.

And math is the unifying method that both scientists and musicians use.

Yes. In physics, the language we use is mathematics. But, because we still don’t completely understand all of the laws of physics, we have to extend those laws to cover the unknown. Likewise, Monk [with his harmonic structures] figured out ways of bending those rules—temporarily and harmonically.

Along with Monk and Coltrane, you highlight other musicians in the book, including Donald Harrison and Mark Turner, who you say improvise to uncover the unknown.

In jazz, there’s always been this debate about traditionalism versus non-traditionalism. But part of the tradition—which was outlined in the formation of bebop itself—was to transcend the tradition. And so Wayne Shorter, Thelonious Monk, Trane, Ornette and obviously Miles Davis epitomize that [spirit]. And that’s what physicists have to do: We learn in the classroom, but when we do research, we have to go beyond the textbook and expand the tradition to create a new physics. A big part of that process is very similar to what jazz musicians do.

In your book, you write about how growing up in the Bronx prepared you for your profession. You say that listening to urban philosophers and hip-hop was a major influence.

Even though we didn’t have [material] resources, we had the Five Percenters and [rapper] Rakim …. We were like the ancient Egyptians and the ancient Greeks thinking about the harmony of the universe. Those basic questions we asked about reality stayed with me, and were reinforced by my experiences growing up in the Bronx.

So you’re making the case that jazz improvisation and African-American culture can offer pedagogical breakthroughs in science education?

Yes. The book is designed and written to point to a new way of teaching physics and science. Physics shouldn’t be presented as some dead, rote material. It should be something the students improvise with. We should excite the students intellectually. They [should be encouraged to] speak out loud and make mistakes. And they’ll realize that the mistakes are the driving force behind learning.

And that’s exactly what happened with Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock: Herbie played the wrong chord. Miles didn’t judge it. He just played the note that made the wrong chord right.

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…