Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

The 10-LP set The Atlantic Years explores how Ornette Coleman changed the shape of jazz.

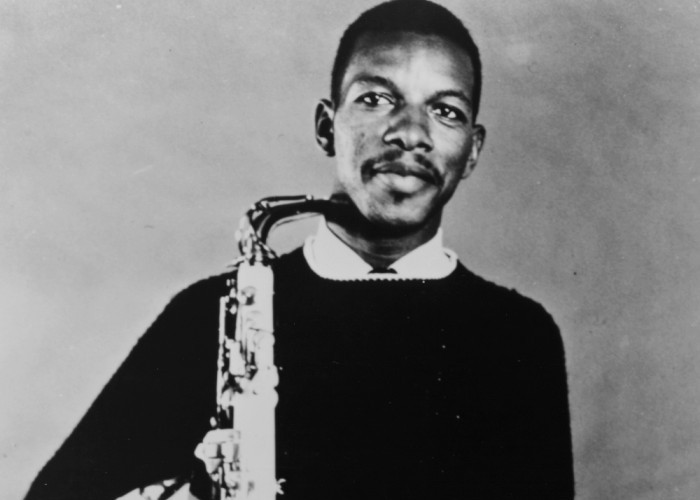

(Photo: Courtesy of Atlantic Records)There’s no question that Atlantic Records was keen to capitalize on Ornette Coleman’s reputation as a jazz revolutionary. Just look at the titles of his first four albums for the label: The Shape Of Jazz To Come, Change Of The Century, This Is Our Music, Free Jazz. Each seemed a calculated poke in the eye to fans who believed that jazz had rules. Ornette was out to erase them.

Yet if you sit down with them now, as component parts to the 10-LP set The Atlantic Years, it’s almost impossible to hear the world-changing power of those albums—ironically because of how completely the saxophonist changed the way we hear jazz. And not just jazz, either. Ben Ratliff suggests in the liner notes that “the plaintive crying rasp Bob Dylan used on tour in front of his electric band in 1966 could have come from lots of places, but something tells me it came from here.” There haven’t been many musical revolutions with that broad an impact.

Astonishingly, Coleman achieved all of this in a mere 22 months. His first recordings for Atlantic were made on May 22, 1959, not even two weeks after his final session for Contemporary, but the music seemed to come from another era entirely. There was no piano on the Atlantic recordings, and no session men, either. Where his earliest albums made a debt to Charlie Parker clearly audible, here he was boldly original, his tone bright and elastic, his lines blues-tinged and richly melodic. The music didn’t follow the rules of post-bop jazz, with regular chord changes and standard song structure, but neither did it leap headlong into anarchy and atonality. Instead, it offered an almost vocalized emotionality, from the wailing, cantorial phrases of “Lonely Woman,” which opened The Shape Of Jazz To Come, to the spare, almost abstracted melancholia of “Beauty Is A Rare Thing,” from This Is Our Music.

It wasn’t just the bandleader, though. The bright, chirpy attack of Don Cherry’s pocket trumpet offered brilliant counterpoint to Coleman’s alto, swapping the muscular virtuosity jazz trumpeters usually traded in for something more evocative and ethereal. Likewise, Billy Higgins’ drumming transformed the standard bop pulse into something lighter and more propulsive, not so much driving the soloists as running playfully alongside them. Ed Blackwell, who replaced Higgins in 1960, beginning with This Is Our Music, had a similar touch, but with a pronounced New Orleans accent.

Above all, there was the bass playing. Before these recordings, bassists provided the foundation and thus were locked into the harmonic and rhythmic structure of a tune. In Coleman’s conception, however, the bass provides counterpoint, and does so with stunning freedom and flexibility. Charlie Haden completely reinvented timekeeping in this band, using double-stops, pedal tones, strummed rhythms and keening arco interjections to provide bass lines that were every bit as compelling as the solos he accompanied. Later, Scott LaFaro added a degree of thumb-position virtuosity to that approach. And for Coleman’s final Atlantic sessions, in March 1961, it was Jimmy Garrison, foreshadowing the sort of aggressive interplay he would bring to John Coltrane’s band eight months later.

Where Beauty Is A Rare Thing, Rhino’s 1995 CD anthology, presented Coleman’s Atlantic recordings in session order, The Atlantic Years compiles the original albums in the order they were released. So, after the first four, there’s Ornette! and Ornette On Tenor, and then several collections of outtakes: The Art Of The Improvisers (1970), Twins (1971) and To Whom Who Keeps A Record (1975). There’s also The Ornette Coleman Legacy, which was never an album before; it contains the previously unreleased tracks that were on Beauty Is A Rare Thing, but omits “Abstraction” and “Variants On A Theme Of Thelonious Monk (Criss-Cross): Variant 1,” no doubt on the logic that those two were recorded not for a Coleman release but for John Lewis’ Gunther Shuller-composed album, Jazz Abstractions (1961). DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Larry Goldings’ versatility keeps him in high demand as a leader, collaborator and sideman.

Feb 21, 2024 10:45 AM

Are you having any fun? Larry Goldings certainly is. Consider just two recent examples:

Scene 1: “If anyone had…