Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

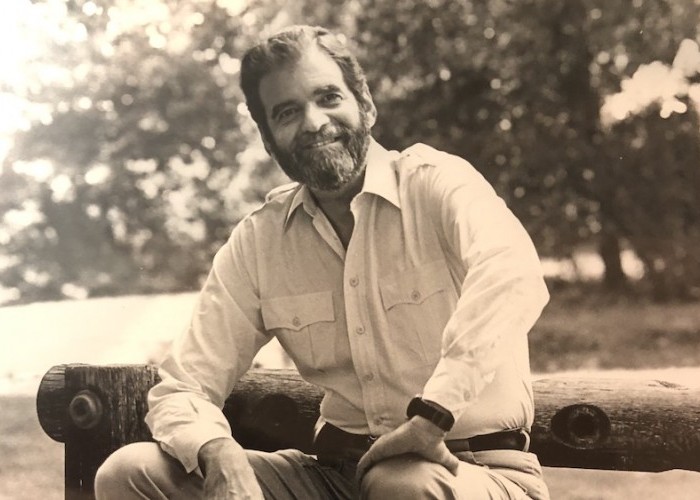

Don Gold, circa 1980s

(Photo: Hedy Weiss)Back in 1956, DownBeat was in a trench of transition but only vaguely aware of where it might lead. The age of big swing bands, which had been the magazine’s milk and honey since its founding in 1934, was over. Waiting for big bands to “come back” or throwing in with rock ’n’ roll were not long-term editorial options. That September, the magazine welcomed Don Gold to its staff. Within 18 months, he would become DownBeat’s managing editor and help map its future covering a rapidly evolving music scene.

On May 2, Gold died after four days in hospice care following complications from a fractured femur incurred on March 2. He was 90.

Born March 13, 1931, Gold grew up in Chicago and came of age musically during the swing years just before and during World War II. After graduating from Northwestern University’s journalism program in 1953, he joined the Army in the waning days of the Korean War. He was assigned to Army intelligence in Heidelberg, Germany, where he lived with his wife and daughter, Tracy, born in 1955. Shortly before leaving the Army and returning home, he applied for a position at DownBeat, where his close friend Jack Tracy (after whom his daughter was named) was editor. He joined the magazine in September 1956.

Tracy, Gold, Dom Cerulli (in New York) and John Tynan (in California) wrote most of the magazine then, with contributions from Ralph Gleason, George Hoefer, Leonard Feather and Nat Hentoff. Gold developed a rather kooky column called “Cross Section,” a kind of free-association interview that invited noted subjects to riff spontaneously on a procession of arbitrary, often unexpected, subjects. Among the topics Gold tossed out were “grilled cheese sandwiches,” “Anita Ekberg,” “Castro” and “dogs,” to which Anita O’Day answered in 1958, “My kind of people.”

Not all readers appreciated Gold’s sense of frivolity and irreverence. “What is Don Gold trying to prove?” wrote one perplexed writer, “that Dizzy Gillespie’s love of dill pickles … helps us understand the man and his music?”

As record critic from 1957, Gold penned early impressions on many now-legendary artists whose reputations were then still under early construction. On John Coltrane in January 1958, he wrote, “Coltrane … makes his debut as leader on this LP. His tone is hard; his conception bluntly surging. There is little subtlety in his playing, but strength and confidence.” He gave Sonny Rollins’ Tour de Force LP four stars, calling him a “a vital individualist … desperately needed in contemporary music.” And on Miles Davis’ Relaxin’ for Prestige, Gold wrote, “After all that walkin’ and cookin’ [referring to his earlier Prestige releases] it’s time for Miles to relax. … He plays with his customary delicate, intricate impact … an attractive set.”

In 1956 DownBeat faced a problem — how to handle the Elvis Presley phenomenon. “Jack Tracy and I realized it couldn’t be avoided,” Gold told me in 1994. “He was establishing a new mainstream and we had to acknowledge it, though we never thought of him becoming the voice of rock ’n’ roll.” Neither did DownBeat readers. “How can intelligent people possibly buy records such as ‘Teddy Bear’?” wrote one jazz lover. “A weird bunch, these rock ’n’ roll fans.” Neither Presley nor rock ’n’ roll would loom in DownBeat’s future. Instead, Tracy, Gold and publisher Chuck Suber focused on a nascent movement for jazz performance at the high school and college levels.

Tracy left the magazine, and Gold became editor in March 1958. He would help guide DownBeat toward a leadership position in a new movement for jazz education, which soon attracted the support of music educators, working jazz musicians and interested advertisers. It was a strategy for the future that revitalized DownBeat’s place in the evolving jazz world.

Gold also enlivened the magazine’s commonplace covers, replacing publicity photos of Liberace and Jerry Lewis with often abstract illustrations by leading artists. He approached David Stone Martin to do a series of covers. Fresh editorial voices came to the magazine under his reign as well. “Don was my first editor at DownBeat in 1959,” recalls jazz writer and archivist Dan Morgenstern. “He asked me to do Milt Jackson, which made me swallow hard as I had no ‘in’ with Bags. His rep said we could meet after a record date at Atlantic, which turned out to be the Bean Bags LP with Coleman Hawkins. Milt was very reserved at first. Then Hawk saved the day by giving me a big hug and saying, ‘He’s OK.’”

In March 1959 Gold resigned from DownBeat for a plum position at Playboy, but he was not finished with jazz. He partnered with Hugh Heffner to create the Playboy jazz poll and the first Playboy Jazz Festival that year at Chicago’s Soldier Field. Gold would remain at Playboy until 1962, when, according to his daughter Tracy, “We moved to New York, where he was book and fiction editor for the Saturday Evening Post, assistant managing editor of Ladies Home Journal and managing editor of Holiday Magazine. He became head of the literary department at the William Morris Agency, which made him a big offer he could not refuse.”

After working for Travel & Leisure in the late ’70s, he returned to Chicago in 1980, this time as managing editor of Playboy until 1984, and finally as editor of Chicago Magazine. After a distinguished 30-year career and the publication of eight books of fiction and non-fiction, Gold joined the faculty of Columbia College in 1989, where he taught magazine journalism until 1996.

His years at DownBeat were the formative ones, however, and possibly the most fun and valued. In his apartment, when he died, was a complete run of DownBeats from 1956 through 1959. According to daughter Tracy, Gold’s ties to those times continued. “Years after DownBeat,” she says, “Dad would keep in touch with Dom Cerulli and the great music historian Jim Maher — such a sweet guy. When I lived in New York, twice a year I would join Dom and Jim for lunch, although they were always frustrated with me because I was of the Dylan and Rolling Stones generation and I never liked jazz. But they were like family.”

Family to DownBeat, too. DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…