Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

Ahmad Jamal will release a new album, Marseille, on July 7.

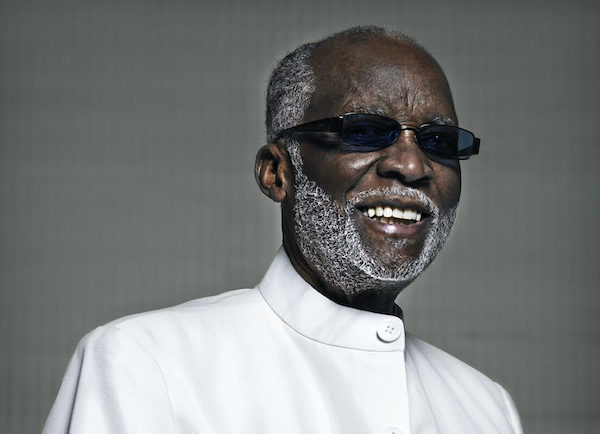

(Photo: J-M. Lubrano)For nearly seven decades, Ahmad Jamal has influenced generations of pianists, from Red Garland to Aaron Diehl. His profound piano style is an amalgam of Art Tatum’s improvisation prowess, Erroll Garner’s ebullient flourishes and Franz Liszt’s prodigious technique. His 1958 hit LP, But Not For Me: Live At The Pershing, spent 108 weeks on the Billboard charts.

For the last few years, Jamal, 86, was rumored to be retired. But now he is back with a new album, Marseille (Jazz Village/PIAS). Supported by drummer Herlin Riley’s Crescent City cadences, Manolo Badrena’s atmospheric percussion and James Cammack’s rock-steady bass lines, the album, due out July 7, features Jamal’s trademarked use of dynamics and spatial discipline, ranging from a rocking rendition of the traditional “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child” and the maze-like “Baalbeck” to the title track, performed as an instrumental with lyrics delivered by French rapper Abd Al-Malik and chanteuse Mina Agossi.

DownBeat spoke to Jamal by phone from his Massachusetts home about his time off, his return to the studio, his legacy and his love of France.

Let’s talk about your retirement.

Well, I never actually said that I retired (laughs). In 2014, at a concert in Prague, I disclosed to my men that I wasn’t going to accept any more engagements. That’s why I never came out with a blanket statement saying I retired.

By the way, I was semi-retired from 1969 to 1972. I founded a record company on 57th Street in New York City. I was producing records and managing. I’ve been touring since I was 17 years old (laughs). I left home as a kid. That’s much too young. Instead of going to Juilliard, I jumped on the road, and I’ve been on the road ever since.

The musicians you work with have been an integral part of your career, on the road and in the studio. Talk about the musicians in your current quartet, starting with James Cammack.

James has been with me for 35 years. He came to me from the Army Band at West Point, where he played bass and trumpet. James is one of my great line of bassists, including Johnny Pate, who did the score to Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack to Superfly; Richard Davis; Wyatt Ruther, who ended his career with Erroll Garner; and Eddie Calhoun, who also played with Errol Garner. And there’s Reginald Veal, who alternates with James Cammack.

The prototype for all of the bassists you’ve worked with was Israel Crosby, who was part of the historic Live At The Pershing recording.

Israel Crosby wrote “Blues For Israel” when he was 16 years old, working for Gene Krupa! And he was one the first African American studio musicians in New York City. [And early in my career] I was his pianist in his group!

And then there’s Herlin Riley, who worked with Wynton Marsalis, and first appeared on your 1985 recording, Digital Works.

When I was in New Orleans, I needed a drummer. And a wonderful trumpet player said I’ll find someone for you, and found me Herlin. That was around 1982–’83.

Riley is the latest in a long line of New Orleans drummers you’ve employed, starting with the impeccable Vernel Fournier, whose second-line syncopations pulsed your biggest hit, “Poinciana.”

There’s James Johnson. He’s from Pittsburgh, but he was born in New Orleans. And of course, there’s Idris Muhammad. But the first one was Vernel Fournier. I found him in Chicago. He was one of the most sought after drummers there. It took some time for me to him to join my group because he was so busy. He was one of the most emulated drummers in the world. People are still trying to figure out how he played “Poinciana” on Live At The Pershing, because he sounded like two drummers.

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Larry Goldings’ versatility keeps him in high demand as a leader, collaborator and sideman.

Feb 21, 2024 10:45 AM

Are you having any fun? Larry Goldings certainly is. Consider just two recent examples:

Scene 1: “If anyone had…