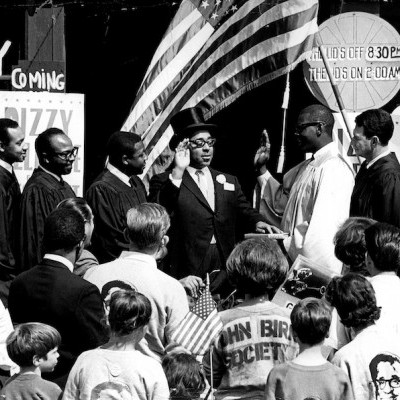

The candidate and his crew, from left, Kenny Barron, James Moody, Rudy Collins, Dizzy Gillespie, Chris White and Shelly Manne.

(Photo: Robert Skeetz)As the hustle on the hustings continues up to election day, with Democrat and Republican decrying one another’s policies and impugning one another’s honor and worse, John Birks (Dizzy) Gillespie plows his own political way in his race for the Presidency of the United States.

The 47-year-old trumpeter from Cheraw, North Carolina, is pursuing his political campaign, offering several solid planks: intelligence and humor about the whole business of running for office, sincere dedication to the principles of Negro rights and the fight to win them fully and lots of the best jazz there is.

Following are excerpts from a recent press conference held in Los Angeles:

Q: In your campaign, do you have any specific criticisms of the platforms of the two major parties? If so, what are they?

A: First things come first. First, civil rights. I think that some of the major civil rights groups are on the wrong track. The real issue of civil rights is not the idea of discrimination in itself but the system that led to the discrimination, such as the schools — the teaching in the schools. They don’t teach the kids about the dignity of all men everywhere. They say that there should be education. Okay. I say education, yes; but the white people are the ones who should be educated into how to treat every man. And the system of discrimination started during slavery time — with the slaves — it’s an economic thing. Of course, we don’t have that slave system at the moment, but we do have something in its place, such as discrimination against people economically.

Economics is the key to the whole thing. For example, if all of my followers said that we weren’t going to buy one single product for three days, think of what would happen to the stock on that one product on the stock market in one day. If it would drop drastically — boom! They would hurry up to protect the investors; they would hurry up to rectify a gross injustice.

Q: How many people do you think would be involved in this, in terms of purchasing power — 20 million … 30 million?

A: There are millions and millions of right-thinking people in this country.

Q: Not just Negro people?

A: Not just Negro people. No, no.

Q: Then you’d probably get 60 million to go along with you?

A: I’d like to see that ... 60 million people wouldn’t buy a product for three days. … There would be bedlam on the stock market. And they would hurry up and do something about this ... thing [discrimination].

The other thing is about the income tax situation. There are certain elements in our society that have better breaks on the income tax situation than others. I say we should make “numbers” legal. A national lottery for the whole country. And everybody — little grocery stores, gasoline stations — would sell books of tickets. All that money would go to the government. Do you realize that millions and millions of dollars a day are taken in “numbers” [which is illegal]. Everybody is a gambler. When you come here on earth, you gamble whether you want to live to see tomorrow. So they should channel those virtues in the right direction.

Q: What about accusations that “numbers” bleed the poor and that only the rich people can back the “numbers”?

A: That’s who’s [the rich] getting all the loot, that’s who’s getting all the money now. But the government would get that money.

Q: Wouldn’t you lose a lot of supporters from the church and from churchgoing people?

A: I notice in some of the churches, they have bingo nights. People go to bingo night better than they would come to see me in a club where they have whisky. Of course, you would have to get the clergy behind you. And then if you hit the “numbers,” if you hit for a dollar, you get $600.

Q: We’ve been hearing so much for the last six months or so about the so-called white backlash. Do you have any comment on that?

A: Yes. In the first place, the people who are affected by the white backlash, we haven’t had them anyway. See? If we are going to judge how to treat a human being by a bunch of hoodlums’ riots in certain places, well, we don’t need them anyway. I have that much confidence in the integrity of the American people that we have enough people to really do something about the situation. So the ones who are affected by the backlash — shame on ’em. We never had ’em anyway.

Q: In the interim period — while the school system is being settled and minority groups are getting equal opportunities — what do you suggest to raise the economic level of Negroes and other minority groups until they have the opportunity to have the same education and, therefore, get the same types of jobs as whites?

A: I would suggest that when an applicant for any employment ... when an applicant comes in to take his ... to decide on his qualifications for a job, it should be behind a screen. This system of discrimination against us is so strong that the moment a black face walks in, we know that we’re going to have to do a little more than the white person to get the job. But when an applicant comes in, and he’s behind a screen, his aptitudes for a job are on paper and you ask him questions or something, and you won’t know what you’ve hired until he has either flunked it or made it.

Q: Could we have your comments on the two candidates of the major parties and their programs? First, Sen. Barry Goldwater.

A: I think his program stinks. I think the senator’s program is ultraconservative. I think that Sen. Goldwater wants to take us back to the horse-and-buggy days when we are in the space age. And we are looking forward, not backward. President Johnson? He’s done a magnificent job.

Q: In what area?

A: In the area of civil rights — for what he has done and with the backing he has. But I’m sure that if I don’t get to be President — which I hope I shall — then I think that President Johnson would make a much, much, much better President than Mr. Goldwater.

Q: We’re in an era in which we are told only a millionaire can be President. Are you a millionaire? [Laughter]

A: Not by any stretch of your imagination. I remember some years ago when I was in Paris, I saw a headline on one of the tabloids — the New York Mirror — which is presently defunct, and it said in the headline: BEBOP MILLIONAIRE IN TROUBLE. There are certain spheres of our media of communication, there are certain newspapers that I don’t believe anything I read in them. This one was preposterous because at that time I didn’t know one bebop musician who had two quarters to rub up against one another.

Q: Seriously, how important do you consider a lot of money is in political campaigning?

A: I understand Gov. Rockefeller … there will be a moment of silence when I mention that name. I understand that he spent in the primaries alone almost $2 million or something like that.

But I look at it this way: Suppose I were a millionaire. That’s a very far-fetched idea. And suppose there was a guy in trouble someplace, and I say, “Here’s $10,000” — with the television camera on me, and the radio — $10,000 clear. [Then] if I were a poor man, say, making $75 a week, and I see a guy who’s ragged and doesn’t have any shoes on and his clothes are in tatters, and I walk up to him and I say, “Come here.” And I go to a secondhand store and buy him $6.79 worth of clothes. My idea of that is, I’ve done more by giving this guy this little gift. I call it having a respect for, and having a big heart for, the little guy.

Q: What do you think of Hubert Humphrey?

A: When we toured for the State Department the first time, in 1956, we were invited to play for the White House correspondents’ ball. I had the good fortune to meet Sen. Humphrey. I walked up to Sen. Humphrey without an introduction. I said, “Do you know one thing? I don’t particularly care for politicians.” He looked at me. I said, “But you are my favorite politician.” He came right back and said, “If you ever come to Minneapolis, I want you to look me up.” So maybe I might get some backing from Sen. Humphrey.

Q: What about the residue from the New Frontier, the men who surrounded President Kennedy and are still in Washington?

A: I can’t say that I blame President Johnson about that because when he repudiated all the men that surrounded the late President Kennedy. … You see, President Johnson has a problem. We loved the late President Kennedy, as did most Americans; we were madly in love with him. My wife cried for weeks and weeks and weeks after his death. But you see Johnson had to do that because in history he wants to be judged by what he did, not for what President Kennedy started. He wants to identify himself with his ideas about social problems that have to be faced. He wants to live and die with his philosophy. I’ll go along with that.

Q: If you were to pick a vice-presidential running mate, who would it be? Or have you done so already?

A: I was thinking of asking Phyllis Diller. She seems to have that sua-a-a-a-ve manner; she looks far into the future. She’s looking into the future. So I’m a future man, I said to her.

Q: Have you approached her?

A: I sent one of my emissaries. I sent one of my emissaries to sound her on that. I understand that she is for it. She was going to vote for me, anyway, so she’d just as well get in there and work.

Q: What about your cabinet? Who would you select for cabinet officers?

A: In the first place, I want to eliminate secretaries.

Q: Why?

A: In French that would be feminine gender, and we don’t want anyone effeminate in our form of government. I’m going to make all ministers.

Minister of foreign affairs: Duke Ellington.

Minister of peace: Charlie Mingus. Anybody have any objections to that? I think it would get through the Senate. Right through.

Minister of agriculture: Louis Armstrong.

Q: Why?

A: Well, you know he’s from New Orleans; he knows all about growing things.

Ministress of labor: Peggy Lee. She’s very nice to her musicians, so … labor-management harmony. It’s harmony between labor and management.

Minister of justice: Malcolm X. Who would be more adept at meting out justice to people who flouted it than Malcolm? Can you give me another name? Whenever I mention this name, people say, “Hawo-O-O-O.” But I am sure that if we were to channel his genius — he’s a genius — in the right direction, such as minister of justice, we would have some peaceful times here. Understand?

Ministress of finance: Jeannie Gleason. Ralph Gleason’s wife. When she can put the salary of a newspaperman — you know it’s not too great, you have to pinch here and there — when she can keep that money together, she’s a genius. So I’m sure that she would be able to run our fiscal policy.

My executive assistant would be Ramona Swettschurt Crowell, the one who makes my sweatshirts.

Minister of defense: Max Roach. Head of the CIA: Miles Davis.

Q: Why?

A: O-o-oh, honey, you know his schtick. He’s ready for that position. He’d know just what to do in that position.

All my ambassadors: Jazz musicians. The cream.

Gov. George C. Wallace: Chief information officer in The Congo … under Tshombe.

We would resume relations with Communist Cuba.

Q: Why?

A: Well, I’ve been reading the newspapermen who were invited to Cuba to look at the revolution there. … It seems Premier Castro wants to talk about reparations. But he wants to talk about it on a diplomatic level, which means respect. I am a man to respect, to respect a country, Cuba, regardless of their political affiliations; they are there, and there’s no doubt about it.

And I was reading in the articles that they’ll be there a while. So I would recognize that we send an ambassador, in an exchange of ambassadors, to Cuba to see if we can work out this problem of indemnity for the factories and things that they have expropriated. I think that any government has that privilege of nationalizing their wealth. It’s theirs; it’s just theirs. So if they want to pay for it. ... Of course, we built it up, we were out there; it wasn’t our country in the first place. But since they built it up and Mr. Castro wants to pay you for it, I think we should accept the money with grace.

Q: What about Communist China?

A: I think we should recognize them.

Q: Why?

A: Can you imagine us thinking that 700 million people are no people? How much percent is that of the world’s population? I think we should recognize them. Besides, we need that business. We’re about to run out of markets, you know. All of a sudden you wake up and there’s 700 million more people to sell something to. And jazz festivals. Can you imagine: We could go to China with a jazz festival and spend 10 years there at jazz festivals. We’d forget all about you over here. We’d send back records.

Q: We’re very deeply involved in Viet Nam; what would be your policy on this situation?

A: We’re not deeply involved enough in Viet Nam. I think we should either recognize the fight or take a chance on World War — is it three? There’s been so many. Either do it, or get out of there. Because every day American soldiers are walking around and — boom! — out, finished, kaput. They’re being killed, and they don’t even know hardly that they’re even at war. We haven’t declared war. So I think we should really either straighten it out — and we have the means to do that — or get out of there. I think we should do it or don’t do it. But if I were President, I’d get out of there. I’d say, “Look, y’all got it, baby. Yeah, good luck.” I’d get American soldiers out of there.

Q: As one of our most prominent musicians, you are aware that automation has played the devil with musicians’ livelihoods. What would your policy be on automation?

A: Automation will never replace the musician himself. We would have to set up some kind of a thing to protect the musician from that. There’s a bill in Congress now — oh, it’s been up for a long time; I get letters from ASCAP and my Society for the Protection of Songwriters; writing letters to senators to get them to vote for this bill — to make them give us part of that money that’s going into jukeboxes. As soon as the jukebox operators find out that you have to pay some money out there, a nice little taste of money, they’ll start hiring live musicians again, I think. Instead of having the jukeboxes there, they’d hire some musicians.

Q: What do you think the role of the musicians’ union should be in this regard?

A: Aw, the musicians’ union! Why did you bring that up? Is this for publication? It is? Ah, the role of the musicians’ union — it has been very lax in this space age. They have wallowed in the age of the horse-and-buggy and the cotton gin. I don’t think they’re doing a very good job.

All they’re doing is taking the money.

Q: In a recent interview, Duke Ellington said that from his personal standpoint he didn’t agree with subsidies for his music. What should your attitude as President be toward federal subsidies for the arts, particularly music?

A: We need subsidies for the arts. I’m a firm believer in that. Since jazz is our prime art, that should be the first thing we should subsidize.

Q: How would you go about that?

A: I’d have to work it out with someone who is familiar with it.

Q: How about a civil-service night club?

A: Now, that’s a good idea. A civil service night club. That’d be nice. I’ve been speaking to Max Roach about an organization composed of jazz musicians to perpetuate our own music. This year at Newport we had a jazz festival. Also they had a folk festival, which was marvelous. I mean, it just got down at the bottom of everything.

Y’see, jazz musicians — they’re so busy being jealous of one another that they can’t get together, so they need some rallying point. Max told me, “You’re the only one that could do it. You should call a summit meeting and have all the guys. Send them a letter; say, ‘Be there!’ And they would be there.” So we were speaking about this. So we’re probably going to get together. ...

But musicians should be on the production end of jazz. Like Shelly Manne is here in Hollywood. He’s a musician who’s on the production end of it, and I’m sure that the atmosphere in his club is different from any club in the country because he thinks like a musician. Just think of an organization of musicians who would dictate the policies of clubs where you play: “Say, look, you’ve got to have a piano that’s in tune — that’s 440 — and lights and maybe little stairs going here and going there.”

Musicians got some ideas. I imagine if you’d turn them loose on ideas of what kind of people they should have in the clubs and how best they could present that music to people, then all of us would benefit by it because all of us would be doing it.

So the musician, with his fantastic ideas about music, if you could channel them into the production end of music, how best we could serve the public — which we are in it to do — I imagine there would be a big rejuvenation of jazz. We could put on four mammoth concerts in one year — one in New York, one in L.A., one in Chicago and one in the Midwest.

They would be in the biggest ball parks, and we’d have people who love jazz, such as Frank Sinatra, Nat Cole (a jazz musician himself), Marlon Brando, Phyllis Diller, Harry Belafonte, all of those people have been helped by jazz. All of them have been helped by it, and I’m sure they would go all out to put a little thing into it. So they would help us with these things.

And we would get an administrator to run it — and pay him, pay him to run it. And let it be run on a businesslike basis, like U.S. Steel is run. We’d have an executive board, a chairman of the board, directors, president and all that jive.

Q: On a personal level, what is your own opinion of Cassius Clay, or Mohammed Ali, as he is now known?

A: My personal opinion of him? I don’t know him that well to pass a personal opinion of him. I would have to know a person very well before I would pass an opinion. … I’m a firm believer in: If you can’t say something good about somebody, don’t say anything at all.

Q: If your opponents in the presidential race start any mud-slinging ... ?

A: Oh, that’s different. A political campaign is something altogether different. And then, afterward, you kiss and make up.

Q: Goldwater, too?

A: I don’t think we would be on too good terms, not on kissing terms, anyway. DB