Eddie Palmieri is a dynamo at the piano: digging deep into a solo, rolling out the complex pattern of a montuno, and leaping from his keyboard to urge on his jazz-hot Afro-Caribbean orchestra as it tears through hip harmonic motifs set in rock-steady claves to thrill smart listeners and swirling dancers alike. As he has since the ’60s with such bands as La Perfecta and Harlem River Drive — and with successive generations of jazz players from vibist Cal Tjader to the final alumni of Art Blakey’s college of musical knowledge — Palmieri rejects anything even slightly corny in Latin dance music to enliven Afro-Caribbean traditions with a fervor for the here, the now, and an envisioned future.

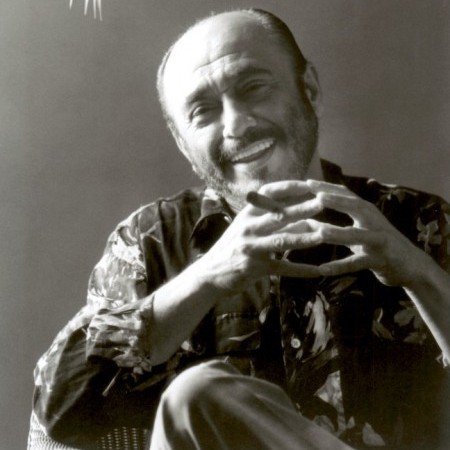

Trim and neatly bearded in the prime of middle age, Palmieri doesn’t call himself a jazz man (“I don’t belong up there with Mr. McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett”), much less a pianist (“I was classically trained by a great teacher, but not having pursued that training; I’m a piano player, maybe an Afro-Caribbean jazz piano player, with aspirations to develop my technique”).

Yet he’s created a double-edged sound by drawing on the talents of Hiram Bullock, Ron Carter, Bobby Colomby, Ronnie Cuber, Cornell Dupree, Jon Faddis, Steve Gadd, Steve Khan, Lou Marini, and Jeremy Steig as well as Chocolate Armenteros, Alfredo De La Fe, Andy and Jerry Gonzalez, Israel “Cachao” Lopez, Nick Marrero, Mario Rivera, Vintin Paz, and Barry Rogers.

In Palmas (Elektra Nonesuch), Palmieri’s first U.S. release in five years, the three-time Grammy winner features trumpeter Brian Lynch, saxist (mostly alto) Donald Harrison, and trombonist Conrad Herwig in charts anchored by superb rhythm players: bongo and bata player Anthony Carrillo, congero Richie Flores, percussionist Milton Cardona, timbales player Jose Claussell, traps drummer Robbie Ameen, and bassists Johnny Torres and Johnny Benitez.

“The quality of my music comes from the musicians who are on my records,” Palmieri explains in a flood of talk as cross-referential and urgent as his music. “But from the first album I recorded, the rhythmic structures have been there. You see, I don’t guess I’m going to excite you; I know I’m going to excite you. It’s because of structures that I sacredly maintain which are Afro-Cuban.

That structure” — he’s speaking of the drums’ organization and repertoire of syncopations drawn from religious ceremonies that came from Africa to the New World via Cuba centuries ago — “will deliver tension and resistance leading to the climax in every composition.

“I knew it intuitively in my early years,” says the enfant terrible of New York City’s Palladium, Merengue Ed of the Catskills, the man also known as “the Sun of Latin Music.” “As a student of Afro-Cuban music I found that all the different structures follow the same pattern, which always delivers that climax. No matter if I have a charanga [flute and violin] band or a big [swing era-size] orchestra like Beny More’s or a [brass-heavy] conjunto like Arsenio Rodriguez’s (he’s the one who started this movement), I keep those structures sacred. For the last 10 years, during which I’ve orchestrated and arranged myself, I’ve never changed. I’ve just looked to extend it more.

“How can you extend on it? Through the world of jazz harmony. I was fortunate to be introduced to jazz harmonies and the Schillinger method by my teacher, the late Mr. Bob Bianco — Barry Rogers took me to him in 1965. Since then I’ve had the most incredible personnel on every album I’ve recorded.”

Palmieri’s justifiably proud of recent bandmembers, including trumpeter Charlie Sepulveda, tenor saxophonist David Sanchez, and bongo-ist Giovanni Hidalgo — but he’s fanatical about his current guys.

“On Palmas I have three great contemporary jazz players. Brian Lynch is the most incredible first trumpet player I’ve ever shared a bandstand with. Donald ‘Duck’ Harrison has just the most beautiful alto sound, the extension of Cannonball Adderley with that New Orleans thing. Conrad Herwig is the most incredible trombonist I have ever met — if I can’t get him for an engagement I’d rather not have a trombonist, because most of them aren’t prepared for the high range I write in, utilizing three-part harmony for the density I need.

“There are charts we follow, sure, but in their solos they’re on their own, free to go on the ride. And the difference in my opinion” — between what Palmieri’s done with his flexible, fiery front line and what he considers lesser efforts — “is that in what’s been called Latin jazz, we’ve often liquified our rhythm section. Which is totally absurd.

“When Latin or Afro-Caribbean rhythms have been added to a jazz album, we’ve had a great jazz trio or quartet with a conga drummer. Nothing wrong with that, it’s been done well — but that conga player is usually in a secondary or tertiary position throughout the album. Depending on who he is, he may get a solo. That is not what I have in Palmas. I’ve got three jazz musicians and five of my own, my exciting dance rhythm section. What I’ve done is an augmentation of what one percussionist, Chano Pozo, did in the ’40s, when Mario Bauza introduced him to Dizzy Gillespie.

“You remember the power of that one percussionist — a tumbero major, singer, dancer, player — to influence a jazz orchestra?Dizzy’s band was not restricted. On the contrary, it had a structure through which to complement the incredible patterns that Chano Pozo offered it.

“He sang those patterns to them. He couldn’t explain it musically, but these great musicians absorbed it. Geniuses like Dizzy were intrigued.

“For Palmas I didn’t say we’re going to do an Afro-Caribbean jazz record, the bongo player won’t come, I’ll only use the timbales player sometimes, but the conga player gets to meet the jazz drummer — that would have been totally out. No, Palmas sets a precedent for how to extend jazz into the most incredible rhythmic patterns, the most exciting in the world, 40,000 years old! From the continent of Africa, picked up by a culture that’s two-to-one African, because the Spanish were influenced by the Moors, mixed with them, took their hand drums, and had a marriage of cultures for a thousand years.”

Throughout Palmas, Palmieri’s jazz horns don’t merely fit into guaranteed structures — they’re stirred to improvisational heights by those ancient rhythms. Says Harrison, whose Creed Taylor production is riding the sales and airplay charts, whose acoustic combo plays adaptations of Mardi Gras Indian themes, and who’s learning how to work with a vocalist by gigging with Lena Horne, “Brian Lynch introduced me to Eddie while we were doing a tribute-to-Blakey tour in Japan. I’d seen him previously, I’d heard his music, and Brian said they were looking for a sax player, so I went to a rehearsal. It really struck me: I wanted to be a part of the rhythms his band was playing, because it’s different than just hanging out and listening to that music. I wanted to learn it.

“I’ve had brief experiences with Latin music before, and I think the rhythms sort of lay easy for me, coming as I do from New Orleans, because the rhythms there are African-based, same as Eddie’s. I’ve had to change my inflections to fit the Afro-Caribbean or Cuban rhythmic aspects that assert themselves everywhere in Eddie’s music. But it’s broadened my whole approach. When you deal with the clave enough, it becomes natural, same as if you’re swinging — you know where the hi-hat is, and you can go as far as you can go from it.

“I listen to all the rhythms Eddie’s got going — bongo, conga, the bassist, the piano — they’re all important. So many rhythms coming at the same time opens you right up. The patterns are based on eighth notes and triplets, which is like what Charlie Parker was doing — Bird being one of the first guys to include both eighth notes and triplets in one line.

“Eddie’s given me records with Cuban flutists and trumpeters and told me to concentrate on them. But I concentrate on everybody, including the singers. I’m trying to bring all of it into the situation. I haven’t really got it under the microscope, but I’ve got the concept. I’m starting to fly around and make some turns.

“One thing I love about Eddie is his free spirit. He goes for the music and listens to the musicians, the same way Art Blakey did, and of course, Duke Ellington, too. That’s the concept of jazz, to discover the sound that’s developing naturally. You have freedom on the bandstand working in Eddie’s band. Why not use it?”

Trombonist Herwig, a veteran of big bands led by Toshiko Akiyoshi, Mario Bauza, Buddy Rich, Clark Terry, and lately Paquito D’Rivera, first toured with Palmieri’s 11-piece traditional salsa dance orchestra in ’86. Now he makes about 75 Palmieri gigs a year.

“Eddie’s always used jazz soloing in the traditional format,” Herwig says. “But with Brian in the band, and by eliminating the singers, we’ve got into more of a jazz context. The horns have moved up front, playing the melodies where the singers would be. And while the trumpet or sax plays a part, the other two of us play backgrounds. Then we switch up. There’s a lot of freedom and interplay. In Salt Lake City recently, with half the audience jazz listeners and half on the dance floor, the scene was like with the Basie or Ellington bands that had people dancing.

“Eddie wants the music to be totally inclusive. His piano is out of the classic Latin style, but the way he plays it is not so strict. I hear Monk in the way he’s able to comp, more freely, even while the music retains its overall structure. The bass holds the timbao rhythm, so he won’t lose the dancers the way bebop did.

“You have to have respect for the genre,” Herwig says of working in any Latin heritage band. “It’s a powerful, forceful music, and you have to have control of your air so you don’t destroy your embouchure. It’s tempting to float over the top of those rhythms, but to be true to the form you have to dip in and explore the rhythm patterns, which takes discipline. Floating over the top doesn’t give you the strength you need to make something happen. The truth is that in Latin music everybody’s a drummer, including the horn soloist.”

Brian Lynch, who worked with Art Blakey as well as Palmieri from the end of 1988 until the Main Messenger’s passing in October ’90, had some gigs with Eddie where he was the lone horn amid a full Latin rhythm section. “We went from playing Eddie’s songs with five horns to me trying to play all the parts I could remember myself,” he says with an audible shudder.“But Eddie’s instrumental ensemble is the hippest jazz group I’ve ever played with, the hippest blowing gig. And I think his Afro-Caribbean jazz term is a cogent one. His format is the same as in any traditional Latin band, with the soloist blowing on the montuno pattern rather than on changes. All the chord changes in jazz sometimes get in the way of the Latin rhythmic format, and when there’s conflict you often get watered-down jazz and watered-down Latin.

“So he’s developed a way to keep all the elements at full tilt. Everything has a phrasing and rhythm; the solo construction becomes more apparent given the limited cyclical framework. People dance to our band, but you can play anything you want over it.

“I try to take things I derive from Eddie’s concept of phrasing and apply them elsewhere, because it’s got universal applications. His horn sections swing like a breezy way of playing straightahead.

“It might be that my most significant dimension is being informed by these experiences,” Lynch suggests. “My composing has certainly been influenced by this relationship, and I have a feeling that in 10 yearsAfro-Caribbean jazz is going to become the mainstream. There are lots of rhythmic resources that haven’t been exploited in jazz so far, and this is a format to do so. Many people don’t know it, but there are lots of players in the Latin world who’ve assimilated jazz and can put something extra into playing straightahead, too.”

Is that what Palmieri’s after? Though his efforts have resulted in the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) instituting a Latin Jazz category for next year’s Grammys, that doesn’t seem his sole aim.

“The last 10 years have been a disaster for our dance form,” he contends, “with a lot of conventional Latin orchestras disregarding the structures I’m talking about. You can die of boredom dancing to them. There’s no excitement, the whole focus is on the singer, the music’s anti-climactic—and to me that’s the worst sin, because the essence of a dance orchestra is to bring happiness to those who brought the rhythms and the scales out of their historic sorrows.

“You know, in a way the dancer is the enemy, the real enemy. That’s how it was when the music started in Cuba, when the music imitated the dance of the rooster and the chicken. When I started playing at the tail end of the Palladium era, after Tito Rodriguez, Tito Puente, Machito, Joe Cuba, my brother Charlie Palmieri with his Orchestra Charanga, and Johnny Pacheco and all that, we were one-on-one with dancers who were so well-versed they were our challenge.

“It was between them and you. You wanted to get them to sweat so they would say at the end of an evening, ‘Oh, Eddie, that was terrific, you knocked me out!’ When I heard that, I knew I’d satisfied the dancing part of the listening audience. When I hear that, because of music we play — ah, then my soul is elated!” DB