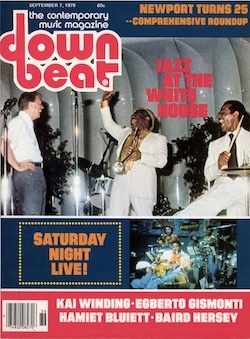

The cover image of DownBeat’s Sept. 7, 1978, issue, which featured in-depth coverage of President Jimmy Carter’s jazz picnic party on the White House’s South Lawn. The historic gathering honored and was honored by a history of jazz that embraced everything from ragtime through the avant garde.

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)The following speech by President Jimmy Carter kicked off the jazz festivities he and the First Lady hosted on the South Lawn of the White House on June 18:

“You are welcome to the first White House jazz festival. I hope we have some more in the future. This is an honor for me — to walk through this crowd and meet famous jazz musicians and the families of those who are no longer with us, but whose work and whose spirit and whose beautiful music will live forever in our country.

“If there ever was an indigenous art form, one that is special and peculiar to the United States and represents what we are as a country, I would say that it’s jazz. Starting late in the last century, there was a unique combination of two characteristics that have made America what it is: individuality and a free expression of one’s inner spirit. In an almost unconstrained way, vivid, alive, aggressive, innovative on the one hand, and the severest form of self discipline on the other. Never compromising quality as the human spirit bursts forward in an expression of song.

“At first this jazz form was not well accepted in respectable circles. I think there was an element of racism perhaps at the beginning, because most of the famous early performers were black. And particularly in the South to have black and white musicians playing together was not a normal thing. And I believe that this particular of music — of art — has done as much as anything to break down those barriers and to let us live and work and play and make beautiful music together.

“And the other thing that kind of separated jazz musicians from the upper levels of society was the reputation jazz musicians had. Some people thought they stayed up late at night, drank a lot and did a lot of carousing around. And it took a few years for society to come together. I don’t know. I’m not going to say, as President, whether the jazz musicians became better behaved or the rest of society caught up with them in drinking, carousing around and staying up late at night. But the fact is that over a period of years the quality of jazz could not be constrained. It could not be unrecognized. And it swept not only our country, but is perhaps the favorite export product of the United States to Europe and in other parts of the world.

“I began listening to jazz when I was quite young — on the radio, listening to performances broadcast from New Orleans. And later when I was a young officer in the Navy in the early ’40s, I would goto Greenwich Village to listen to the jazz performers who came there. And with my wife later on we’d go down to New Orleans and listen to individual performances on Sunday afternoon on RoyalStreet, sit in on the jam sessions that lasted for hours and hours. And then later, of course, we began to learn the individual performers through phonograph records and also on the radio itself.

“This has had a very beneficial effect on my life. And I’m very grateful for what all these remarkable performers have done. 25 years ago the first Newport Jazz Festival was held. So this is a celebration of an anniversary and a recognition of what it meant to bring together such a wide diversity of performers and different elements of jazz in its broader definition that collectively is even a much more profound accomplishment than the superb musicians and the individual types of jazz standing alone.

“And it’s with a great deal of pleasure that I, as President of the United States, welcome tonight superb representatives of this music form. Having performers here who represent the history of music throughout this century, some quite old in years, still young at heart, others newcomers to jazz who have brought an increasing dynamism to it, and a constantly evolving, striving for perfection as the new elements of jazz are explored. George Wein has put together this program, and I’d like to welcome him now and thank him and all the superb performers whom I met individually earlier today. And I know that we all have in store for us a wonderful treat as some of the best musicians in our country — in the world — show us what it means to be an American and to join in the pride that we feel for those who’ve made jazz such a wonderful part of our lives.”

Black music has chased the golden calf of respectability almost from the beginning. First there was Paul Whiteman’s Pygmalion approach to the music, which had relatively little to do with real jazz. Then in the late ’30s true jazz came to Carnegie Hall. There was the famous Benny Goodman concert and then the celebrated Spirituals To Swing programs that brought Goodman, Basie, Lester Young, Charlie Christian, Sidney Bechet and Big Bill Broonzy together in one concert. Many others would play Carnegie from then on.

The symbolic importance of Carnegie Hall brought artistic recognition to jazz. A measure of official public recognition came in the mid ’50s when first Louis Armstrong, then Benny Goodman and Dizzy Gillespie made State Department tours to friendly nations overseas. Then there was Goodman’s famous mission to Moscow in 1962. Finally the White House itself began to embrace jazz, first in the Kennedy days and then Nixon in 1969. For Nixon the occasion was Duke Ellington’s 70th birthday. It was the most popular thing he ever did in a public career spanning 30 years. But Nixon was honoring a man, not an art.

On June 18, seven days before the start of the 25th annual Newport Jazz Festival, President Carter corrected that oversight. He and the First Lady hosted an unprecedented picnic party on the South Lawn facing Constitution Avenue that honored and was honored by a history of jazz that embraced everything from ragtime through avant garde. The President honored jazz, Newport founder George Wein honored the musicians, and the musicians honored each other in a concert of extraordinary quality and integrity considering the brevity that necessity imposed on all concerned.

Before the concert began, Wein went about impressing everyone with the “serious time problem we have.” Eubie Blake was limited to a strict five minutes. “Well, I’m no stage hog,” Eubie said in mock seriousness. Wein reminded him that he’d probably go on for 90 minutes if nobody told him not to. And he might have. The 95-year-old pianist and composer had had a red letter weekend. His new show, Eubie, opened in a Philadelphia tryout the night before to unanimous rave notices.

The idea began, appropriately enough, not with the President but with George Wein himself and a New York enthusiast called Les Lieber. Wein first contacted Rhode Island Congressman Fernand St. Germain on the idea of a White House occasion marking the Newport Festival’s 25th anniversary. St. Germain agreed and encouraged Wein to suggest it to White House Social Secretary Gretchen Poston. This he did, and the planning promptly began.

Wein assembled a list of 35 musicians with a view toward including all who have “played a vital role in the history and evolution of jazz.” All would come at their own expense, according to the Newport office. This is what the list looked like: Eubie Blake, Kathrine Handy Lewis, Dick Hyman, Doc Cheatham, Mary Lou Williams, Teddy Wilson, Jo Jones, Milt Hinton, Roy Eldridge, Clark Terry, Illinois Jacquet, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, McCoy Tyner, Max Roach, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, George Benson, Tony Williams, Dizzy Gillespie, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Lionel Hampton, Chick Corea, Louie Bellson, Ray Brown, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Benny Carter, Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, Billy Taylor, John Lewis, Sam Rivers, George Russell and Joe Newman.

As you can count, the list spilled over the imposed limit of 35. So several assumed the role of “musicians in attendance” and limited their activities to introducing other musicians. These included Sam Rivers, John Lewis, Gerry Mulligan and others. But in some cases the music beckoned too strongly. During “How High The Moon,” MuIligan borrowed a clarinet from a member of the Tuxedo band and joined in. In addition to the players, Wein’s list reached out to include other members of the jazz world. John Hammond was there with his wife, Esme. So was Jerry Wexler, Bruce Lundvall, Clive Davis, Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun, George T. Simon, Stanley Dance, Leonard Feather, Dan Morgenstern and Elaine Lorrilard, who, with husband, Louis, underwrote the first Festival at Newport in 1954.

Other invitees (some of whom did not attend) included Buddy Rich, Gregg Allman, Herb Albert, Harold Arlen, Lucille Armstrong, Dave Baker, James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte, Dick Cavett, Lena Horne, Quincy Jones, Boz Scaggs, Flip Wilson and Andrew Young. The invitations went out early in May with requests that recipients remain quiet about the approaching event until the official announcement came from the White House June 1. Of course, word got out before. John S. Wilson broke the story in the New York Times weeks before.

The weather could hardly have been better as musicians arrived early in the middle of the afternoon, June 18. Groupings were arranged and tunes tentatively selected, although no rehearsals were attempted. President Carter appeared, greeted everyone, and posed for photos with each musician individually.

“These guys were never prouder to be jazz musicians,” Wein said later. “It wiped me out.”

It was only one of the many moving moments, however.

Eubie Blake, whose career is older than jazz itself, opened the program with “Boogie Woogie Beguine” and his own classic “Memories Of You.” He then jumped up, took a deep bow and bounded off stage to rejoin his wife, Marion, in the audience. His sheer presence was moving by itself.

Another link to the beginnings of jazz was provided by Kathrine Handy Lewis, daughter of composer W. C. Handy, who sang her father’s “St. Louis Blues” as if she were casting a mystical spell out over the crowd. Doc Cheatham and Dick Hyman made the performance even more haunting with their accompaniments. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Mrs. Lewis’ performance was its breadth. She sang choruses of lyrics rarely heard and probably unfamiliar to even the most sophisticated listener. It was a revealing performance by an artist who has recorded relatively little over the years. Collectors will recall her as the vocalist on the Fletcher Henderson record of “Underneath The Harlem Moon” from 1933. It was a song producer John Hammond desperately tried to dissuade Henderson from recording because of the embarrassing Jim Crow lyrics.

Perhaps John recalled that as he listened on this sunny afternoon on the South Lawn. Certainly the most emotional moment of the concert involved no music at all, only the memory of music. George Wein looked down toward the front row to a man slumped in a wheel chair. He called for a round of applause “like you’ve never given before in your life.” It was for bassist Charlie Mingus, victim of a stroke as well as a serious disease of the nervous system that has left him virtually paralyzed. A companion of Mingus’ lifted his limp arm from his lap to acknowledge what was by now a standing ovation. Mingus smiled and made a remark that could not be heard. Then President Carter came over, greeted him, put his arm on his shoulder and stood with him for a moment. Mingus was overcome with emotion. Tears poured down his face as he wept uncontrollably. For those in the audience who knew Mingus and felt his legendary and often violent fits of anger and emotion rage in times past, the present scene, though sad, was thoroughly in keeping with this intensely emotional man whose great contribution to music has rested so much on his ability to harness his emotions to his music.

The entire program was broadcast by National Public Radio (NPR), and doesn’t need to be reviewed here. Presumably tape recordings abound among jazz fans everywhere. The sound of George Benson and Herbie Hancock playing real jazz will make them rare treasures.

President Carter remained for the entire program. Frequently he would leap up after a set, walk over to an artist and greet him. During a powerful performance by Cecil Taylor, the President looked on with a slightly bewildered fascination, somewhat perplexed at the meaning of it all but stunned at the overwhelming craftsmanship of the work. Under a magnolia tree off stage right afterwards Carter went over and told Taylor he’d never heard anything like it.

The final official set of the evening began as Lionel Hampton beat out “How High The Moon” and then (after “Georgia On My Mind”) launched into “Flying Home,” calling it “The Jimmy Carter Jam.” Illinois Jacquet bit into a familiar tenor solo with fierce power. Then when it was all over, Carter jumped up on stage.

“This is the first time anything like this has happened at the White House, and I can’t understand why. Because it’s obvious that this is as much a part of America’s greatness as the White House or the Capitol. You can leave if you want, but I’m going to stay and listen to some more music.”

At this point Pearl Bailey, who was seated near the front with Attorney General Griffin Bell and his wife, surprised everyone by jumping up on stage for a spontaneous number. Hampton, without his glasses, didn’t recognize her. He thought she was an amateur and tried to shoo her away. What’s more, he confessed, “She looked white to me.” “I look white to a lot of people,” she snapped back before taking everyone into a version of “In The Good Old Summertime,” an odd number to draw upon for a jam session. But as it turned out, it was an effective one. When it was over, Lionel decided he wanted to switch to drums, but Pearl literally chased him away, saying husband Louie Bellson was the only one she could play with. Hampton, looking none too pleased, returned to his vibes. A short “St. Louis Blues” ended the evening.

As the crowd relaxed and began to leave and musicians started packing their instruments, Carter approached Dizzy Gillespie behind the stage. They chatted for a moment and then Carter made a request. “Why don’t you do that number you did at the White House a few months ago?” Dizzy said the concert was over; it was too late. “Oh, come on,” Carter urged. “Do it by yourself.” Dizzy then said that he’d love to but there’s one other piece he would like to have him hear too. “Great,” the President said. So Gillespie grabbed Max Roach, who was standing nearby, and told him to get a hi-hat cymbal. Wein went to the stage again and said Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach have had a request from the President.

After a trumpet-cymbals duo featuring a long solo by Roach, Gillespie said he would now play the presidential request. But there were certain diplomatic strings attached, to wit that the President would perform the vocal. Thus did the classic “Salt Peanuts” enter the realm of American political history. The election of 1980 may see the first bebop campaign song.

Although the idea for the occasion began with George Wein and was basically conceived as a promotion for the Festival, it’s a tribute to all concerned, especially Wein, that it never once became self serving.

A decade ago, such a celebration would have been impossible. The avant garde was fuming with anger. Much of jazz music was fired by the spirit of revolution. Even older musicians were estranged. Max Roach, responding to the bankruptcy of American political leadership then, flirted with communist ideology. Jazz itself was in a state of civil war unmatched since the early days of bebop.

There was also Viet Nam, Lyndon Johnson, civil rights and the emergence of a youth counter culture. America seemed to be breaking apart. How reconciled and tolerant everyone behaved toward one another last June! All the old wounds from the old battles seemed healed.

Some guests who might have been there were busy honoring other commitments: Count Basie, Buddy Rich, Benny Goodman. But there were no boycotts, no demonstrations. Only the enigmatic Miles Davis stands by his curious and now rather dated pose of isolation. The rebelliousness that characterized jazz for so many years is perhaps spent — for the time being at least.

President Carter seemed an unlikely patron and benefactor of jazz, and no one really was sure what to expect. “Carter thinks the king of swing is Wayne Hayes” was one of the better lines going around. When he opened the concert at 6:30 he said, “I hope we will have more in the future.” When it all came to an end and the results were in, no one doubted it. Especially President Carter. DB