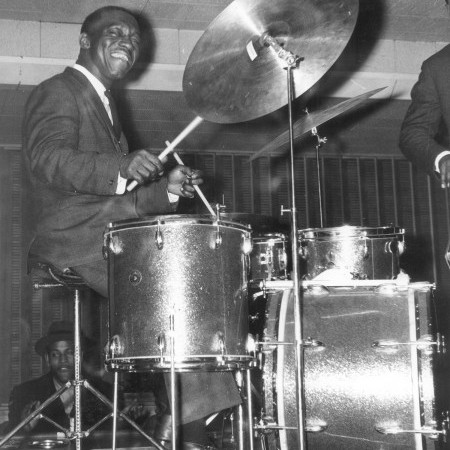

Art Blakey

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/R. Howard)Art Blakey sat on the edge of the bed in a Detroit hotel room. Dressed only in a T-shirt and shorts, his powerful arms stabbed the air with a cigarette as he talked. “Talked” is perhaps too mild of a term—Blakey seldom just ”talks.” You could almost feel his excitement and enthusiasm.

“We’ve played a lot of countries,” he said, “but never has the whole band been in tears when we left. My wife cried all the way to Hawaii.”

What had prompted the tears and Blakey’s enthusiasm was the Jazz Messenger tour of Japan earlier this year. He said that it was the first time he and the members of the group (Lee Morgan, Wayne Shorter, Bobby Timmons and Jaymie Merritt) felt really appreciated. “It was the first time I experienced real freedom, too,” he added.

The appreciation, or more correctly, adulation, began when the Messengers alighted from their plane at a Tokyo airport. Other passengers included film stars Edward G. Robinson and Shirley MacLaine, but the thousands who had waited at the airport until the early morning were as eager to greet the jazzmen as they were the Hollywood personalities. The group’s records blared forth from the airport loudspeakers. The Japanese fans buried Blakey and his men in flowers.

“It was like a florist’s shop,” the drummer said. “They wanted to make a speech, but I couldn’t. I just cried.”

But they were showered with more than flowers; Blakey said the band members shipped back $5,000 worth of presents. One restaurateur presented the musicians with a set of expensive sport jackets. Blakey’s wife received a costly Kimona. At the tour’s end, a ceremony was held to give Blakey a copy of a 60-minute sound film made during the band’s tour.

“Monte Kay (Blakey’s manager) offered to pay for it,” Blakey said, “but the people were very insulted. It was a gift. They didn’t want money for it. None of the things they did for us was a gimmick. No gimmicks, just love.”

Art Friends Association, the only cultural exchange group recognized by the Japanese government, according to Blakey, was responsible for the Jazz Messengers’ touring Japan. The organization took a survey of Japanese jazz fans, and Blakey’s group proved most popular. The Messengers’ records consistently head the lists of the most popular jazz albums in the Far Eastern country.

The tour included concerts in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. In most of the cities, Blakey said, the stage lighting was extraordinary. “They had studied our records and knew what we would do,” he said. “Then they improvised lighting effects to fit the mood of the music.“

At one of the concerts, the members of the group were in their dressing rooms when music filled the air. “Who put on of our records?” asked trumpeter Morgan. The music duplicated one of the Messengers records. “That’s no record,” answered Timmons. “That’s the band what goes on before us.”

“The Japanese musicians are good,” Blakey said, lighting another cigarette. “They can copy anything. They’re a wonderful people. We came to one town, and a boy watched me set up my drums. He made some sketches of how I had things arranged. I never had to set up myself again; he had everything just like I had it.”

Seemingly as impressed with the Japanese as the Japanese were with the group, Blakey expressed amazement at the vigor of the people.

“Everybody’s busy,” he said. “You don’t see any bums hanging around poolrooms. It’s a great industrial nation—always trying to improve this and that. Their TV is terrific. They’re very advanced in color TV. We did an hour program, and the cameraman had to know everything we were going to do so they could chart what camera angles and colors to use. During the telecast, they never looked at the band, only their charts. It was amazing.”

Blakey and his men found that they learned more than most tourists do in Japan. “We didn’t go there to teach them anything,” he said. “We ate their food, stayed in their houses. We spent most of our time with the people, talking. They showed us things that other people don’t get to see. I listened to their music, but I can’t say I understand it. It’s a different scale than the one we use. But it has a story and meaning of its own.”

The Messengers found the language quite difficult to master (“We did learn to say, ‘Thank You.’”). But when they return to Japan at the end of the year or the first of next, they plan to be better prepared in the language. A Columbia university teacher is tutoring the band.

“Most of the people speak English,” Blakey said. “But they were confused about the word ‘funky.’ They had the idea that a funky musician was a Negro musician dressed in tattered clothes, with a don’t care attitude. When they saw our uniforms and how we bowed in appreciation of the applause, this surprised them. They’d taken the term non-musically.”

Blakey and his Messengers have a busy schedule ahead of them. Besides working clubs in his country, plans have been made for the group to travel to even more far-flung places than Japan. If all goes well, they will visit Europe this summer, India in September, Australia in October, and the USSR in November followed by the second tour of Japan.”

If the USSR tour comes about—and Blakey said he feels that it will—the Messengers will be the first jazz group to tour the country officially since World War II. (The Mitchell-Ruff Duo played in Russia in 1959, but they were ostensibly part of a college glee club touring the country.)

The possibility of the USSR tour stems directly from one of the group’s Japanese appearances. At a Tokyo concert, 17 ambassadors attended. With the USSR ambassador was that country’s minister of culture. He was so impressed with the group that he wrote his government suggesting that the Messengers tour Russia. Negotiations are still in progress.

“We’ll get through to those people if they’ll let us,” Blakey said about the USSR tour. “Even if they reject our records, I think a personal appearance will be successful.”

Although the concert the Russian minister of culture attended was successful and potentially fruitful, Blakey and the band members experienced a minor disappointment. The U.S. ambassador failed to show up at the performance, although he had received an invitation. He failed even to send a representative an invitation. He failed even to send a representative. At the end of the concert, each of the attending ambassadors was presented a large bouquet of flowers. The flowers intended for the U.S. ambassador were placed in his empty seat.

“At first,” Blakey said, a deep frown creasing his face, “we felt pretty bad about it. Here we were representing America, and nobody there from our own country. Regardless of how he felt about jazz, he should have come or sent somebody. But then we forgot about it, figured he had something more important to do.”

Despite his apparent delight at the prospect of touring foreign lands, Blakey nonetheless bemoaned the fact that he and his group must work outside the United States in order to receive the acceptance he feels they deserve.

“We also get more money,” he said. “You can’t get acceptance or money in this country, which is damned shame. If you want to keep a band together, they’ve got to get a good salary. Club owners here can’t afford it. Besides, the guys work too hard in the clubs, especially the horn men. They won’t last long in the clubs—they’ll wear themselves out.”

Blakey warmed to two of his favorite subjects, club owners and the acceptance of jazz and jazzmen:

“If the club owners would leave us alone and not run things on a conveyor belt, things would be better. Some of them look on musicians like they were machines—put in a quarter and out comes music. You don’t create just like that. You’re like meat in a butcher shop. They cut you up.

“Jazz has to be treated especially gentle,” he continued. “Surroundings have to be kept pleasant. Working clubs as they are now is a bore. Concerts are the best. God’s been good to us; we can go out of the country and get recognition. But we’ll keep knocking over here; someday they’ll let us in. A things are now, we can’t get to the people.

“Things are getting better, though. But they’re moving slow. Mass media is key. Until now, TV has been too commercial. We worked some shows, but the emcee had to get into the act, making fun of the clothes we wore or beating a drum when he didn’t know how. That stuff hasn’t got anything to do with the music.”

Blakey also had strong things to say about jazz festivals:

“They’re nothing more than vaudeville shows. There shouldn’t be more than two groups, one in the afternoon and one at night. Whoever heard of 10 groups in one program?”

He said he feels that there is a lack of confidence among club owners and promoters in this country. “If they just let the guys play, the people will enjoy it and be entertained. But they don’t believe it can be done better over here. But we’ll wait and see. It’ll happen.”

The small, muscular drummer’s confidence radiated in the dark room. He was still in his T-shirt and shorts, but he was clothed in a garment that can’t be bought—hope.

DB