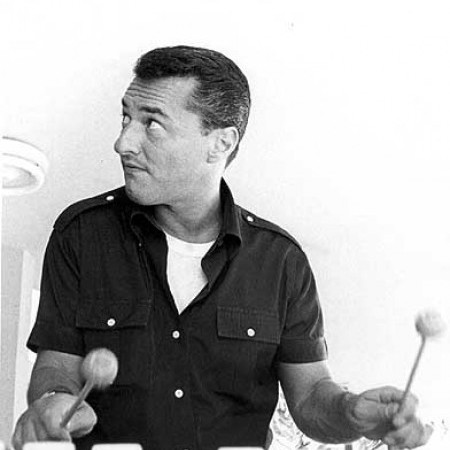

Terry Gibbs

Can recordings alone make a successful band?

Almost any self-styled sage in the music business will assure you that this is virtually impossible because a band, in order to be a growing concern, i.e., a consistently paying business, must work on the road, must hit the one-nighter grind most of the year in order to get the public exposure that can build a national reputation.

The sages may be right, and certainly the success on records of such leaders as Hank Mancini has nothing to do with a permanent Mancini orchestra of the one-nighter variety. But in a more limited way the Terry Gibbs big band is a recording success, too, and so far as the vibist is concerned, his albums keep the spirit of the band alive.

Spirit is the key word here. It has to do with the roaring jazz produced by Gibbs and 16 others when they assemble on a bandstand for an occasional club engagement or concert.

It is certain that jazz spirit, captured in the Gibbs albums, thundered out of the grooves so dynamically it compelled the voters in DownBeat’s 10th annual International Jazz Critics Poll to elect the band to first place in the new-star category this year. What is remarkable is that the majority of the critics who voted for Gibbs’ band did so without ever hearing the band in person. All they had to go on were three LP albums—Launching A New Band, Swing Is Here and The Exciting Terry Gibbs Big Band. The few critics who did hear the band in person dug it on its own stomping ground, Hollywood, or perhaps at the 1961 Monterey Jazz Festival.

Pickings are lean in Hollywood for a big band. Thus has it been, of course, since the early 1950s. As has been pointed out on many occasions in the past, a big band cannot expect to remain of the West Coast and make it. This is particularly true of a big jazz band. So the miracle of the Gibbs band’s endurance is only partially touched by economic considerations; the real secret is wrapped up in the words spirit and loyalty—to the idea of this big band.

In the beginning there was a seemingly prosaic domestic decision: Terry Gibbs and his wife, Donna, decided to settle down in California. He bought a suburban home with a swimming pool in the San Fernando Valley and from time to time sallied forth with his quartet for engagements in the East.

It had been Gibbs’ practice, under his recording contract, to record one big-band album a year. These sessions were made with studio musicians, and the arrangements generally were the first-class work of such as Al Cohn and Manny Albam. It was a nice musical arrangement for Gibbs; he could record and work night-club and concert jobs with his quartet, commanding top money, and then, for kicks, he could cut loose and indulge his real love for big-band jazz.

If the quartet led to the big studio band on record, it led also to the formation of the presently existing aggregation, Gibbs recently recalled the origin.

“A movie columnist friend of mine, named Eve Starr,” he said, with his staccato, machinegun delivery, “called me one day in 1959. She told me about this club in Hollywood. Place called the Seville. She said the place was dying and the owner wanted to change the policy. He really didn’t know whether he wanted jazz; he wanted anything that would bring customers into the joint. Eve suggested I go talk to him. His name was Harry Schiller.”

Gibbs talked to Schiller and signed a contract to work the Seville with the quartet. At this time he was preparing his annual big-band album. He already had a dozen arrangements and planned to cut the LP in Hollywood with a top-notch personnel.

There was the problem of rehearsal. Musicians union rules prohibit unpaid rehearsals for recordings but permit a band to rehearse for a night-club job.

“I made Schiller a proposition,” Gibbs said. “I asked him if he’d let me take the big band into the club Tuesday night only for the same amount of money as the quartet was getting. Schiller said it was okay with him if the quartet did business. If the quartet brought in some customers, he said, he didn’t care if I brought in some customers, he said, he didn’t care if I brought in a band of apes on Tuesday. So we were set.”

The rehearsals began, and it was immediately evident that in the Hollywood musicians, Gibbs had a group unlike any of his previous studio big bands.

The weekend prior to the band’s Tuesday one-nighter, Gibbs did a guest appearance on the Sunday night Steve Allen Show. Allen gave him a hefty plug.

During the next two days an unprecedented telephone campaign added word-of-mouth publicity to the debut. The forthcoming event—for it had indeed become an event—was literally the musical talk of the town.

The band’s opening was a sensation. In the jammed Seville, scattered through the audience, was a remarkable celebrity turnout. Among those who attended were Fred MacMurray and June Haver, Johnny Mercer, Stuart Whitman, Ella Fitzgerald, Steve Allen, Dinah Shore and Louis Prima. The turnout of musicians was unparalleled.

By the end of the evening it was a foregone conclusion that the band would play the following Tuesday, too. In a week, those who had not heard the word in time for the debut were ready to come out and dig. The second Tuesday was as successful as the first. And so, for nine consecutive Tuesdays the new Terry Gibbs big band made West Coast jazz history.

The fact that the band began that first set with the knowledge that there were only 11 more numbers in the book didn’t matter to Gibbs and his men.

“We just kept an arrangement going for 10 or 20 minutes,” Gibbs grinned. “With long solos and different backgrounds made up by the guys in the sections, it was no problem.”

By the second week, Gibbs recalled, other arrangers, such as Bill Holman and Med Flory, had contributed arrangements to help expand what was probably the smallest big-band book in jazz history.

In retrospect, Gibbs noted the band could perhaps have continued indefinitely at the Seville on Tuesdays had he not received an offer to take it into the now-defunct Cloister on the Sunset Strip for three weeks. He accepted the offer and the owners’ proviso that the band must not play any other Los Angeles venues on their nights off.

The Cloister engagement was a mistake. For one thing, the room was too small. For another, the customers, who largely came to hear singer Andy Williams and laugh with comedian Frank Gorshin, who shared the bill with the Gibbs band, were not prepared for the shock of hearing the band at full throttle. From Gibbs’ point of view, the engagement was less than successful.

By now, Gibbs was obsessed with a desire to keep his band working and exposed to a growing following. Morale in the band was possibly unprecedented.

“The guys made a rule,” Gibbs said. “Nobody takes off for another job. If a guy did, he was out of the band. And this they did for $15 a night!”