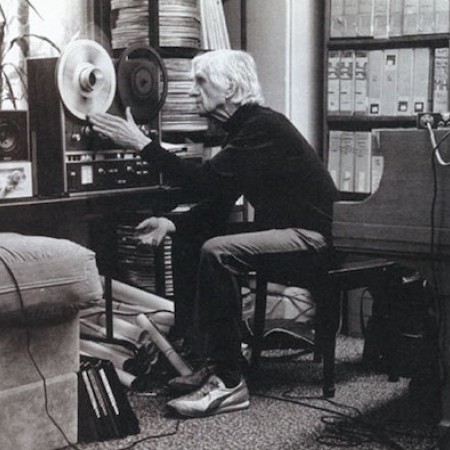

Gil Evans (1912–1988)

(Photo: Carol Friedman/gilevans.com)Among jazzmen, particularly player-writers, Gil Evans is uniquely admired.

“For my taste,” Miles Davis says, “he’s the best. I haven’t heard anything that knocks me out as consistently as he does since I first heard Charlie Parker.”

Coincident with Miles’ recent tribute, Capitol released a few weeks ago the first complete collection of those 1949–’50 Davis combo sides which were to influence deeply one important direction of modern chamber jazz—Birth Of The Cool.

Evans was perhaps the primary background factor in making these sessions happen, and he wrote the arrangements for “Moon Dreams” and “Boplicity.”

“Boplicity” is listed as the work of “Cleo Henry,” a nom-de-date for Davis, who wrote the melody after which Evans scored the written ensembles. “‘Boplicity,’” declares André Hodeir in Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence, “is enough to make Gil Evans qualify as one of jazz’s greatest arranger-composers.”

Despite these and other endorsements from impressive jazz figures, Evans is just a name to most jazz listeners. In the past few years, he has written comparatively little in the jazz field; but his influence on modern jazz writing through the effect of his work for the Claude Thornhill band of the forties and the Davis sides has remained persistent.

“Not many people really heard Gil,” Gerry Mulligan explains. “Those who did, those who came up through the Thornhill band, were tremendously affected, and they in turn affected others.”

Gil has now decided to return to more active jazz participation and is writing all arrangements for a Davis big band Columbia LP to be recorded at the end of April. He’s also become more interested in creating original material, an area he’s largely avoided up to now.

Evans once again is at a crossing point of his career.

He was born Ian Gilmore Green in Toronto, Canada, on May 13, 1912, and took his stepfather’s name. Gil is self-taught and says, “I’ve always learned through practical work. I didn’t learn any theory except through the practical use of it; and in fact, I started in music with a little band that could play the music as soon as I’d write it.”

Evans first learned about music through jazz and popular records and radio broadcasts of bands. Since he had no traditional European background either in studying or listening, he built his style entirely on his pragmatic approach to jazz and pop material.

Sound itself was his first motivation. “Before I ever attached sound to notes in my mind, sound attracted me,” he says. “When I was a kid, I could tell what kind of car was coming with my back turned.”

Later, “it was the sound of Louis’ horn, the people in Red Nichols’ units, like Jack Teagarden and Benny Goodman, Duke’s band, the McKinney Cotton Pickers, Don Redman. Redman’s Brunswick records ought to be reissued. The band swung, but the voicings also gave the band a compact sound. I also was interested in popular bands. Like the Casa Loma approach to ballads. Gene Gifford broke up the instrumentation more imaginatively than was usual at the time.”