“I heard Lou Donaldson for the first time, and that down-home feeling of his was a gas,” said Bunky Green about one of his early influences.

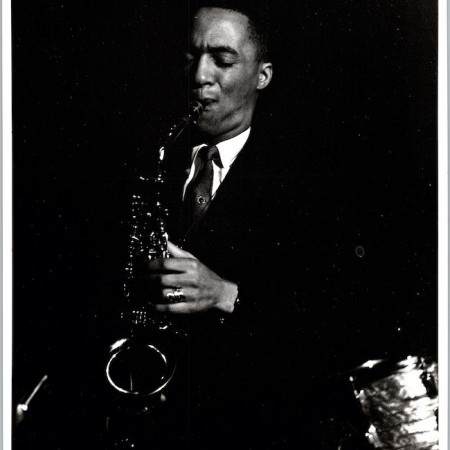

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)“Keep up the intensity, keep up the intensity!” urged the diminutive alto saxophonist. He was talking to his new group in the midst of a recording session, but he could just as well have been talking aloud to himself. For most of his life, 30-year-old Bunky Green has been keeping up the intensity of the one thing with which he is most familiar — making music.

Watching the dapper altoist at work brought to mind a statement he had made, though at the time he said it, he had shied a little at the possibly corny overtones: “I think many times while I’m playing that it might be my last moment on earth, and I want to feel that my passing through has meant something to somebody. At one point or another, I feel like I’m in an attitude of prayer.”

Music, Green said, was a way to affirm his existence, adding, “No musician plays for himself alone. You play, not just for self-satisfaction, but so that people will recognize your ability. We all exist through others; without people to recognize your ability — the crowd that says, ‘You’re making it’ — you wouldn’t have a reason to do any of it.”

“I’ve heard many musicians say that they wipe out the people when they play, but basically they’re playing for someone else all the time. Subconsciously they build a shield around themselves to keep from being hurt. They say, ‘I don’t care whether you dig my playing or not — this is where it is!’ And maybe it is where it is, but all of that talking is just like that toothpaste ad, an invisible shield.”

Green is as avid a communicant verbally as he is musically. While discussing his career, he injected notes of comedy or drama as freely as he does on his horn.

When Green was a junior high school student in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he had a friend who played alto saxophone. After petitioning his father, Green as well became the owner of an alto — nickel plated. He took lessons at school, along with “a thousand other guys in the same room,” and began listening to the latest waxed word from the jazz heroes of the day.

He soon found that the attention of musicians and listeners alike was focused on tenor saxophone players, not altoists. Dexter Gordon, Wardel Gray and Lester Young were the vanguard for those who influenced Green’s thinking in those days. He decided that tenor was to be his instrument, and he traded in his practically new alto for the larger horn.

Then, as fate would have it, he began hearing talk of a sensational altoist named Charlie Parker. Green listened but initially felt that he was hearing “too much being played at once” — he didn’t like it. The local hipsters’ acclaim for Parker’s innovations persisted, however, stimulating Green’s curiosity, and the more he listened the more he liked. Shortly, Green, now a high school freshman, was back at the music store, trading his tenor in on another alto.

During his high school years, Green played local gigs with schoolmates. After graduation, he decided to go to New York City, where he had been told that musicians abounded and that there were many even younger than he who would fall in clubs with their instruments and blow the walls down.

He found that he had been put on about the youngsters, but what he’d heard about the grown men was right.

“I heard Lou Donaldson for the first time, and that down-home feeling of his was a gas,” Green said. “I saw and heard much more — but Lou was enough to send me back home to tighten up my thing.”

After playing and practicing around Milwaukee a while longer, the young altoist returned, in 1958, to the big city. This time things began to happen for him. Another Milwaukeean, pianist Billy Wallace, told Donaldson about his gifted homeboy, and, sound unheard, Donaldson referred Green to a bass player friend who was looking hard for a reed man to augment his group.

“I got this phone call from Charlie Mingus,” Green said. “He told me to be at his house within the hour because he was taking the group to West Virginia that night.”

If it hadn’t been for his Milwaukee friend, Green reflected, he would have stayed home that night. But he went — and he worked out. From there it was back to New York, then Philadelphia and out to the West Coast. The year was 1958 and California bristled with various musical influences.

“A funny thing happened to me out there,” Green recalled. “Some guy came up to me after one of the sets and asked me if I’d ever thought of ‘playing free.’ Of course, I didn’t understand what he meant. He explained that he was talking about dropping any reliance on chord structures, wiping out the bar lines, letting the emphasis be on structure. Well, it left a big question mark in my mind at the time, and about a year later I found out who the cat was and what he was talking about: everyone was saying Ornette Coleman, Ornette Coleman.”

Green felt his store of musical knowledge growing as he continued to play with Mingus. One night at the hungry i in San Francisco, a young music student, carrying an alto, asked to sit in with the group.

“Mingus liked this cat, and I thought he sounded great,” Green said. “Little did I know that this cat, John Handy, was soon to replace me with Mingus.”

Because of personal commitments in Milwaukee, Green had to return home. He had been with Mingus for eight highly instructive months, met many musicians, heard and played much music, and acquired healthy new perspectives regarding the way jazz was being played around the country.

“I thought when I left Mingus,” Green said, “that I’d clear up my business in a short time and return to the group, but, as it turned out, I was never able to get back.”

Instead, Green set about reconsolidating his forces in a rather uncharacteristic way for a former Mingus sideman: “I picked up a job in Milwaukee fronting a group in a strip show — and I doubled as emcee. We’d play tunes like ‘Fever,’ ‘Tequila’ and ‘Night Train’ — the kind of thing the girls could bump and grind to.”

But the gig paid money, some of which Green was able to save with the intention of going back on the jazz circuit. Meanwhile, Chicago jazz entrepreneur Joe Segal had heard about the altoist, and he sent word that he’d like Green to come to town for one of his sessions. Green arrived at the old Gate of Horn and found himself in the company of tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin and a host of other well-known jazz lights, such as the late tenorist Nicky Hill.

Inspired anew, Green returned to Milwaukee, determined to resettle in Chicago at his earliest opportunity. When it came, he found himself welcomed on the scene and was soon playing around the Midwest with trumpeter Paul Serrano. It was with Serrano that he cut his first record, Blues Holiday, which was supervised by Cannonball Adderley for the Riverside label.

Then, Green recalled, he had a rather sobering experience in the record business.

“I cut some ‘free’ things with Vee Jay records — rather like what some people call avant-garde today. The company shelved them at the time. There were some great musicians on those sides, too, like bassist Donald Garrett and pianist Willie Pickens. One of the albums, My Babe, with [pianist] Wynton Kelly, [trumpeter] Donald Byrd, [bassist] Larry Ridley, [tenorist] Jimmy Heath and [drummer] Jimmy Cobb, was just released a few months ago on the Exodus label. I wonder what the influence on my career would have been if those things had been heard then, five years ago.”

Reflecting further on this point, Green says that the time has passed when he can concentrate solely on experimentation, even though he would like to.

“I can’t afford to satisfy my ego to that extent any more; I have a wife and kids dependent on me now,” he said. “If I played exactly what I feel all the time, I know I wouldn’t get my message across to more than a handful of people around the country — and that’s not enough to make it.”

Though conscious of his responsibilities, Green still has his inner drive. In the next breath he was talking about the requisites of greatness: “I don’t just mean playing jazz, you know. I mean Einstein, Napoleon. … They all had to be selfish to be great — it’s an occupational hazard. I even yelled at my wife this morning when she interrupted my practicing. ... I was apologizing later, of course.”

A clause in Green’s 1960 contract with Vee Jay required that he play weekends at a Chicago jazz club called the Bird House, in which a Vee Jay official held a financial interest. Things went well there for a time, but the ill-fated aviary had to close its doors, as did many other clubs at this point, for lack of audiences, leaving Green nearly broke.

Faced with having to look outside his customary arena for employment, he was on the verge of hiring out to the first bidder. Then he heard that the big-band business was the most profitable thing going on in Chicago, especially the band headed by drummer Red Saunders, which was the house band at the Regal Theater on the South Side. Hastily, Green sharpened his reading, packed his alto and headed for Saunders’ house, auditioned successfully, and remained with Saunders for nearly 18 months.

But the cost of living was rising and salaries paid sidemen were not keeping pace; so Green was in search of more lucrative employment once again. He found it — and a new love — with the Latin band of Manny Garcia.

“Outside of pure jazz,” Green said, “I love Latin best because the rhythm is so strong I can play anything from bop to ‘free’ — anything I want. When I first joined Manny, I asked him what kind of things he wanted me to play, and he said, ‘Play anything, man — we’ve got a beat for it.’ On top of this, I began learning Spanish.”

In the fall of 1963, Green enrolled in Wright Junior College, majoring in sociology. Jumping into things there musically, he became a fast friend of the school’s band director, John DeRoule. One spring afternoon, DeRoule told him the band was going to Notre Dame University the next day to play, and he wanted the altoist to come along.

That night Green packed his toothbrush, expecting nothing extraordinary. Only after finding a large audience in front of him, he said, did he realize that something special was in the offing.

As it turned out, Green was judged the best saxophonist at the 1964 Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival. Seated in the audience were representatives of the U.S. State Department. They teamed Green with a group from the West Virginia State College for a summer tour of North Africa. Later, Green said, he had to endure good-natured ribbing from the Chicago jazz fraternity for “taking advantage of those kids.”

But Green, no older than some of “those kids,” was as eligible to participate as any of them — and hadn’t even known it was a contest beforehand.

While in North Africa, sightseer Green wandered into the Algerian Casbah. Along one of the narrow streets he saw a group of musicians seated in a circle, playing strange instruments, one of them a curious bagpipe.

“The instrument had only one pipe,” Green recalled, “and the guy kept squeezing the bag under his armpit, filling it with air. It was the first time I had heard this music played in person, and I was intrigued by the way he played so many figures around a single tonal center.

“As soon as I left there I damned near got lost, wandering down Casbah streets I know I shouldn’t have been on, trying in vain to find one of those bagpipes.”

Green says that his experience with the tonally centered music he heard in Algeria led to the introduction he played on “Green Dolphin Street” on a subsequent album, Testifying Time.

While Green was in Algiers, Eric Dolphy died in Europe. But the altoist, who had known and played with Dolphy on many occasions since his days with Mingus, did not hear of the tragedy until he reached Paris, on his way back to the United States.

“Buttercup [Bud Powell’s wife] told me about Eric,” he said. “I had met her some years back when I was playing with Mingus in Philadelphia on a bill with Bud, Lester Young, Wade Legge and a bunch of other great cats. It was kind of a sad scene because we talked about Eric’s death and Bud and all the changes he was going through.

“Then I saw Bud, and heard him play, and I knew he wasn’t himself anymore.”

When he returned to Chicago, Green searched for new outlets for his music. Though he had been recorded with the Serrano group, he had never headed his own date, and bassist Connie Milano felt that this oversight should be corrected immediately. Milano pounded the pavement for Green’s cause until he reached A&R man Esmond Edwards. Thanks to Milano and Edwards, Green said, he began a series of dates with Cadet Records that has so far produced three albums.

Then Green joined the Latin group with which he is currently associated, that of singer-percussionist Vitin Santiago. I’m really knocked out playing with these guys,” he said. “I speak some Spanish and the other guys speak some English, but I wouldn’t have been able to convey the finer points of the musical ideas without Vitin — he’s my translator. Besides, this cat has a photographic memory — if you can call it that — for music. All I’ve got to do is ask him how such and such a tune goes, and he can riff a little bit of it; he remembers them all!

“Another thing, for a jazz musician like me, there is a tendency to get involved with waltzes and all kinds of different harmonies. In spite of everything, I was still getting wrapped up in complex theme structures, and I found that with a Latin group this doesn’t always have the impact that it has in straight jazz. Now, with Vitin, all the heads are simplified; the focus is on the solos, and I can really put Bunky in it.”

Green has just recorded his first album with the Latin group for Cadet, and, in addition, the soon-tobe-released album features the altoist on the new electronic saxophone. One of the first to record on the instrument, Green said that, though the device is, in his estimation, not quite perfected, it has merit for some players.

“We had trouble recording it, and the alto needs more work done on it,” he said. “But it’s going to get better as it goes along. It’s a boon to a person who doesn’t have a strong, dynamic tone.

“The biggest feature is the double octave, but when I blew forcefully into the horn, the sub-bass line was lost. I would recommend using a different amplifier for the alto than the one used for the tenor, since I’ve heard that the tenor works better than the alto.”

Until recently, in addition to other commitments, Green worked the Monday night sessions at Mother Blues in Chicago’s Old Town, and many of the musicians who came were avant-gardists. Though grounded in the canons of harmonic structure, Green is receptive to influences taken from the divergent concepts of big band men, boppers, and “free” and Latin players; he found the new musicians a welcome addition to proceedings.

At the Mother Blues sessions, however, many patrons would leave in a huff, having heard sounds past their understanding. This sometimes caused more than a little confusion in the club.

“What Chicago, and a lot of other cities, need,” Green said, “are a few more places to play and a few tolerant listeners. Sometimes at Blues I would just have to step out front and say, ‘Come on and blow, man,’ because I remember how I felt when I was tryin’ to get together with the bop thing.

“Some of the new musicians in Chicago have a good thing going. Richard Abrams, in particular, has a deep insight and a well-thought-out process. Other cats are not so well schooled, but they seem to have a natural talent for the new thing.

“People are going to have to try and understand the new music, as they try to understand the times. The new music is so connected to the times; there is an urgency in cats, because we all realize that we don’t have 10 more years to study. We all have to say what we have to say, now.”

Green says that one of the first signs of old age, particularly for a musician, is the rejection of new things.

“When you start canceling things out simply because you don’t understand them, or they’re something other than what everybody else is playing,” he said, “then chalk up a mark against yourself because you’ve begun to get slow — you might have let something of value slip by you.”

Green referred to Sonny Stitt as a model of the ecumenical spirit: “I look at cats like Stitt, blending the Bird things with things that came before and after. Yet, when you hear Stitt — even though he is a blend of many styles — he doesn’t sound like Bird or anybody else but Stitt! I try to do as Sonny does, because I love the good — what I think is good — in all of it, and I try to syphon off the best.”

Things appear to be brighter than ever for Green, and it shows in everything he says and does. He talks with little regret about past adversities and much enthusiasm about the future: “I’m going to Europe again this coming spring. If I have some bookings arranged before I leave, fine; but I’m mainly going to hear what’s being played over there . . . mainly to relax and absorb the atmosphere. I’d like to get down to Algiers again and deepen my insight on that scene; I’m really interested in hearing more of that tonally centered music.

“When I return to this country, I intend to start a program of study, spend time working the jazz circuit across the country, and — most of all — to keep an open mind, to keep on digging. The thing with me is to get knowledge together, because with knowledge comes freedom.”

That’s Bunky Green: sincere and intense, so much so that he may sound square to the jaded. But the odd thing is that he means it. DB