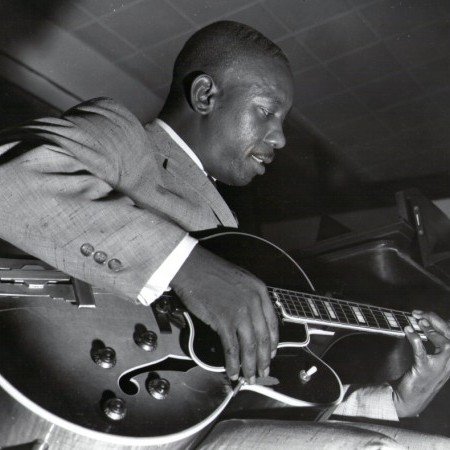

Wes Montgomery plays at the Essex House Hotel in Indianapolis in 1959.

(Photo: ©Duncan Schiedt/Courtesy of Resonance Records)In that 1968 DownBeat interview, Montgomery credited Adderley for raving about him to Riverside Records founders Bill Grauer and Orrin Keepnews — leading to the prominent record deal that would take him out of Indianapolis a decade earlier. That was when the guitarist was holding court at the Missile Room on Indiana Avenue. In the liner notes to The Wes Montgomery Trio, Keepnews claimed, “I first heard about Wes in no uncertain terms and twice on the same day: to be precise, on September 17, 1959.” He went on to add that the same day Adderley “charged into the Riverside office” urging him to sign the guitarist, Keepnews read Schuller’s article, “Indiana Renaissance,” published in the September 1959 issue of The Jazz Review.

Schuller was effusive in discussing Montgomery’s playing, describing techniques that have since become familiar to every jazz guitarist. As Montgomery performed without a pick, his solos would move from introducing a single-line melody to using octaves as a way of playing in different registers simultaneously and then concluding with block chords — all of which were tied together with a perfect sense of form and executed relatively quietly. Varying accounts mention that Montgomery’s subdued volume derived from his not wanting to disturb either his wife, or his neighbors, while practicing.

Schuller wrote, “In its totality, it is playing that combines the perfect choice of notes — i.e. purity of creative ideas — with a technical prowess that the jazz of yesteryear, the jazz of the jam sessions and cutting contests had, but that, I’m afraid, the jazz of today has almost completely lost.”

What’s striking is that Keepnews and Riverside worked quickly enough to sign Montgomery and bring him, along with pianist Rhyne and drummer Parker, into the studio in only three weeks to record The Wes Montgomery Trio (aka A Dynamic New Sound) in October 1959. Considering how disciplined and industrious the guitarist was, he must have prepared himself for this transition onto a larger jazz playing field. That’s where the recordings that make up Echoes Of Indiana Avenue come in.

Producer Michael Cuscuna, who would play a significant role in finding and helping release the recordings decades later, believes that the tapes were made as audition reels for Montgomery. It’s likely, then, that they would have been circulating the following year.

“They were [recorded] live, but done professionally live,” Cuscuna explained. “It wasn’t a small reel-to-reel at a table in the back of a club. So they were done for Wes, his manager, or whoever. They sound like they were made with the idea of getting Wes a record deal.”

The performances on Echoes Of Indiana Avenue illustrate what Schuller described in that 1959 article, though it doesn’t take too deep a listen to discern the congeniality that Indianapolis veterans remember. On a terrific interpretation of “‘Round Midnight,” Montgomery builds up from a deliberate pace alongside Rhyne’s organ lines, and their blend continually stops and starts in unexpected moments, yet the constant surprises conclude with a perfect sense of resolution. At other times, like on “Take The ‘A’ Train,” Montgomery delivers his uncanny technique at a tempo that remains startling. Echoes concludes with “After Hours Blues,” an apparently spontaneous jam in front of a club audience where Montgomery revels in strong chords and distorted effects. Whoever is in the audience clearly loves it all.

And then the tapes vanished for 50 years.

ConnectIcut, California and Cyberspace, 2008–’09

As a producer for Mosaic Records, and instigator of many historical releases, Cuscuna has seen not just his share of important albums, but also numerous projects that never moved past the idea stage. In 2008, someone told him that guitarist Jim Greeninger had put up early tapes of Montgomery for sale in an eBay auction. The tapes went unsold, but Cuscuna was excited about what he heard, particularly because unreleased Montgomery tapes are such a rarity.

“What was evident was that without any identifying mannerism, here was a guy who could just burn,” Cuscuna said. “He was harmonic and melodic and swung like hell. What comes through here is a musician who is a full- throttle improviser, who is accomplished on his instrument, and has a great range.”

Cuscuna bought the tapes from Greeninger with the intention of passing them on to Blue Note for release. But his timing was not ideal.

The private equity company Terra Firma had bought Blue Note’s parent company, EMI. “Everything there slipped into complete dysfunction,” Cuscuna said.

“Terra Firma disconnected catalog from each of the labels and tore the labels apart,” he added. “We’d go to meetings and people would discuss it or forget to discuss it, and the layers of bureaucracy were just getting worse.”

So, Cuscuna offered the tapes to George Klabin and Zev Feldman at Los Angeles-based Resonance Records. All of them worked to nail down the details of the sessions. They called in additional experts, like Baker, who helped point out the other musicians.

“We had good luck identifying the players simply because there was a limited number of people who were playing at Wes’ level at that time,” Baker said. “Part of it is simply knowing their associates, knowing who they normally play with and knowing the idiosyncrasies of the players themselves. I recognized Sonny Johnson on drums, and Mingo would have been more likely to play something more advanced than swing, more repeated notes from time to time.”

Montgomery’s estate was eager to get on board with the project. Buddy Montgomery’s widow, Ann Montgomery, has expressed that she’s glad this release provides another example of all three brothers’ musical accomplishment.

Cuscuna contends that in the future, independent labels like Resonance will have more flexibility than the majors in terms of clearing all the legal hurdles required to issue such previously unavailable recordings.

The surviving participants on Echoes Of Indiana Avenue are just excited that it is out there and presents the personality that they always will remember.

“Wes was a person who never stopped,” Jones said. “He played for everybody, and he loved everybody. He would always have a smile and was always there for you.” DB