Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

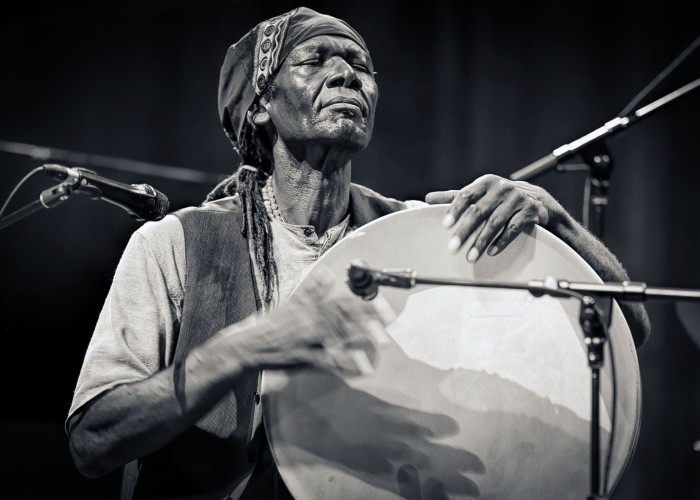

Hamid Drake takes to the frame drum at Chicago’s Logan Center during this year’s Hyde Park Jazz Festival.

(Photo: Michael Jackson)In May, Hyde Park Jazz Festival Executive and Artistic Director Kate Dumbleton learned she’d lost a $30,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was one of nearly 560 grants canceled, leading to a $27 million evisceration of funding to hundreds of arts organizations nationwide. This only multiplied Dumbleton’s determination to forge ahead with a much beloved community event that has already parried the ravages of the pandemic and other funding cuts. Not to be dissuaded by recent characterizations of Chicago as some kind of all-out war zone, people came out in droves to promenade along the leafy expanse of the Midway Plaisance on the city’s South Side. Public donations increased to over $40,000, 30% up from 2024. Powers-that-be may not be invested in the edification of America, but its populace clearly are.

Festival headliner Jason Moran, who performed a solo recital at the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, was compelled to resign as artistic director of Jazz in July, a position he’d held at the Kennedy Center for 14 years. He’d been responsible for curating and developing one of the largest jazz programs in the U.S. Moran’s rendition of Duke Ellington’s “Single Petal Of A Rose” ended his set (before encores) at the filled-to-capacity gothic revival chapel. His encore of “Come Sunday” was a tad premature given that the 10 p.m. start time for the final act of the festival’s principal day had been brought forward an hour to attract attendees who’d started to moderately decline for the late show, post pandemic. Dumbleton added a Sunday show and an extra booking at the Logan Penthouse so there was no shrinking of the 34-program event, which drew record attendance.

Moran’s concert was in some ways a cross section of what the Hyde Park Jazz Festival does very effectively: alternating challenging material with crowd-pleasing fare. As with the festival, he defied expectation. Thus, during his Ellington program, “I Got It Bad” became blithely insouciant and “It Don’t Mean A Thing” a willful refutation of cliché. Such could be regarded as contrarian, but a stunning interlude occurred when Moran brokered a phantasmagoric departure from “Black And Tan Fantasy.” Using protracted, rumbling, clustered intervals in the lower octave with sustain pedal, he conjured ominous reverberations that “offered glimpses into a mind that sought to connect earthly sound with divine vibration,” as was said of Russian Symbolist composer/pianist Alexander Scriabin. Moran, a visual artist, too, also made connections with Gordon Parks’ photographs of Billy Strayhorn and Ellington at work (or rather, not at work, but recumbent on a couch with ice cream, as in the case of the latter).

Another outstanding pianist and composer performed earlier in the day in a similarly hallowed space, The Hyde Park Union Church. Ryan Cohan has been a regular at the festival, always presenting ambitious, scrupulously conceived projects. But this time he insisted there was less of an overarching agenda and declared, “Let the music do the talking.” Despite his own feisty improvising and the virtuosity of his sidemen (multi-reedist John Wojciechowski blew intensely on three saxophones and flute), Cohan’s poised but gear-shift writing, with its classical impressionism, world music and down-the-line jazz confluent streams, is always the guiding principle. It helped that his vision was realized by an executive rhythm section, including drummer George Fludas and bassist Lorin Cohen. There were moments and smiles all round when the KAIA String Quartet (Victoria Moreira, Naomi Culp, James Kang and Hope Decelle) hit a downbeat (or an offbeat accent) in dramatic sync with Cohan’s jazz quartet, since Cohan’s music can be metrically demanding. The first movement of his four-piece Prism, “Radiant Angles,” modulates from a 12/8 feel in 4/4 to a straight-eighth 3/4 over the coda and ending vamp. “The returning groove in the last movement, ‘Resilience,’ is in 4+4+6,” said Cohan when asked to deconstruct the energizing bounce built into his scores. “The groove feels like a duple meter but the string pizzicato and piano figure feels like it’s playing groups of 5 within it.” The combination of superb ensemble craft and poignant, well-balanced strategy make Cohan’s music impressive but not pretentious or overwhelming.

Immediately after that classy debacle, percussionist Hamid Drake celebrated his 70th birthday at The Logan Center Performance Hall in the company of the stellar Chicago quartet that has convened at his biannual solstice communions with fellow percussionist Michael Zerang. This trio, with the addition of the distilled soul of saxophonist Ari Brown, was specifically requested by Dumbleton and Dave Rempis, the festival’s director of operations and finance.

“We’ve had this group together, with Josh Abrams, Jason Adasiewicz and Ari called Indigenous Mind for a while,” said Drake, already back on the road in Europe, shortly after the festival. At the Logan, Drake introduced the band, mentioning that he wished he could match the virtuosity of vibraphonist Adasiewicz on the drums. The way Adasiewicz assails his instrument, to be sure, is something to behold. Customary shaggy mallets, smashed down on aluminum bars from a height still elicited a resonant pellucid sound, then Adasiewicz deployed the stick and hair of a bow. Meantime, Drake’s rhythms were always varied, often betraying awareness of reggae and ska breakbeats.

What sets Drake’s performances apart beyond originality and dynamism is his spirituality. He took to the frame drum at Logan Center and chanted, “Suratul Fatiha,” which means “The Opening,” the first chapter of the Quran. He also sang a seven-line song in Tibetan that is key to Vajrayanna Buddhism.

“So, are you polytheist?” DownBeat asked Drake.

“Before I chose to make music my profession, I was planning on pursuing degrees in comparative religions,” Drake responded. “I still study sacred traditions, not just through books but with the living representatives of those traditions: great women and men I became close to who have caused me to learn many wondrous things which have helped me honor humanity and all life.”

Such a comment, evidenced captivatingly onstage, might be a key takeaway for the record crowd in attendance at the 19th Hyde Park Jazz Festival. Folk of all color, creed and persuasion intermingled in the sunshine on the picturesque Midway Pleasance at this open-border, fence-free, free-admission festival. The egalitarian, culture-supportive attitude exuded by attendees created a weekend oasis of sanity and sanctity in a troubled world. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…