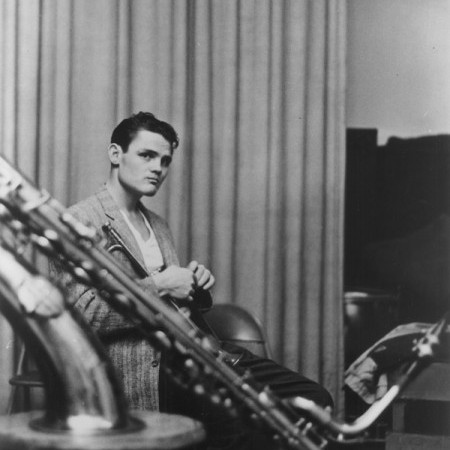

Chet Baker (1929–1988)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)“And later, in Paris (after I had been deported from England), although I had only been there a week, I was included in a bust of people that they had been watching for one month before I got there. Because I had come to town, they included me in the bust also, although they hadn’t seen me in any of the places they were watching or dealing with any of the people involved.

“I was there 24 hours, and everybody was getting sick—they give you a fix in the police stations until they get all the papers typed up and signed, sealed; they give you a fix every three hours—and I never asked for anything the whole time. So, I went up to one of the detectives and explained it to him. When he checked around, they let me go. But the judge who was handling this bust never did lighten up on me during my whole stay in Paris. He called me back every two weeks, had me examined by police doctors, found me clean, and still he didn’t lighten up on me until I went to Spain.”

In England, Baker was the recipient of a “gift” from a pharmacy clerk—narcotics he said he did not need—as he was registered with a doctor under the British system of treating narcotics users. He said he told the man the next day that he didn’t want to become involved, and, since drugs were so controlled in England, the clerk should be careful or Scotland Yard would be around.

The police did come around, and the clerk admitted stealing the drug.

“They told him,” Baker said, “‘You have no record. We’ll make it easy on you if you’ll tell us who you gave it to.’ So, he didn’t go to jail. I went to jail for 40 days and got kicked out of England.”

Now, finally back in the States, did Baker, pursued at every turn, justly or unjustly, feel that some organized force was against him? “Well, I might have had that feeling,” he answered quietly. “I really didn’t know.”

Yet his current playing displays optimism and a real desire to play, certainly not the marks of a defeated man, especially today, when so many musicians do not sound as if they even enjoy what they are playing.

“Well, that’s really the one thing they can’t touch,” he said, referring to his spirit. “I have a great deal of disrespect for the police department and the correctional people and the way they handle drug addiction, and I’ve suffered greatly at their hands. Not for very long, usually, but so many times that I made up my mind not to let it affect my playing in any way because, after all, that’s the only thing I know how to do.

“I’ve always been an optimist,” he said with a half-laugh. “It’s funny, but I’m kind of mixed up because, by nature, if I’m not playing, I’m depressed usually—melancholy, quiet—but if I’m playing, it seems to change. Now, I play very ‘hard.’”

When I went out to the Cork ’n’ Bib to hear Baker, shortly after his return to New York earlier this year, I commented on his fiercer attack and generally more virile style (DB, May 21). At the Cork ’n’ Bib, he was playing a borrowed trumpet, because his flugelhorn was in the shop. More recently, at a recording session, I heard him playing flugelhorn, and there was no diminution in Baker’s fire.

“Playing this flugelhorn,” he said and paused, “It’s so hard to play, you wouldn’t believe it. Nobody would, unless it was somebody who plays one. The mouthpiece is deeper and wider, and it takes so much air to fill out this horn. You were there at the date. If I had been playing steadily, right up to the time of the date, I could have gone through that eight or 10 times without getting tired ... . Playing that tune—and it only goes up to high C—if you’re not playing steadily, you can’t make it. After a couple of times, you’re finished.”

Baker began playing flugelhorn a couple of months after his deportation from England and return to Paris. His trumpet had been stolen from the Chat Qui Peche, and a friend gave him a flugelhorn. Baker has been playing it nearly a year-and-a-half now and says he has given up trumpet.

But how did Baker acquire the new strength in his work? How did his conception change?

“I can’t really say how it happened,” he mused. “I did a lot of thinking—I had my horn during the time I was in prison in Italy—17 months—and a lot of playing, a lot of thinking about music during that time.”

Baker trailed off for a moment and then continued: “I wish you could have heard the band in Philadelphia one night, one set or two sets on one night. The band stretched out so far; we were playing some advanced melodic and rhythmic things.”

The band Baker refers to is one he formed soon after his return. It consisted of tenor saxophonist Phil Urso, an old associate of Baker’s from an earlier quintet who had been living in Denver, Colorado, for a while, and, more recently, had been gigging around the Midwest with Claude Thornhill; pianist Kenny Lowe; bassist Jymie Merritt (formerly with Art Blakey); and drummer Charlie Rice. With the exception of Lowe, this is the group with which Baker recorded and has been touring together ever since. The regular pianist is Hal Galper, who used to play in Boston with Herb Pomeroy’s big band.

“I think this band is going to have a lot to say,” Baker said, “because Hal writes some nice tunes.”

I hadn’t heard any of Galper’s compositions, but judging from the repertoire I did hear, I wouldn’t imagine this to be a far-out group when judged in light of some experiments that have taken place since 1959, the year Baker left for Europe.

“I haven’t heard Ornette Coleman, and I’ve only heard Coltrane on records,” he said. “The people I’ve heard since I’ve been back have been Charlie Mingus at the Five Spot—I went down there and wasn’t impressed at all by what was happening. On the ensembles, the things were ragged. Maybe it was because of the constant changing of men in the group. And Mingus was continually saying things and screaming at different personnel in the band. I went down to Birdland and listened to Gerry Mulligan’s Concert Band, and that didn’t kill me, either—Gerry stopping the band in the middle of a tune and starting them over again ... kind of a rehearsal, audience participation and so forth. Maybe it was because there weren’t too many people there, and he felt he might as well rehearse or something. ... And I went down to hear Zoot Sims and Al Cohn at the Half Note. I think Al Cohn is marvelous. I like Zoot, and I have a lot of respect for Zoot, but hearing him play alongside Al Cohn, it just seemed to be in a different class. Zoot can play, too, but Al is so much stronger, so much more definite. He knows where he’s going, and it comes out so natural.”

Although he has not heard Coltrane in person, Baker decried the marathon solo: “Forty-five minutes is a long time to be blowing; a lot of people get bugged. He gets hung up playing a little rhythmic figure, keeps on playing the same thing, just breaks up the time differently. I’d rather listen to Stan Getz or Al Cohn, myself. But I have heard him play some things that are really beautiful.”

“I think there’s still a lot to be said within the framework of the standard tunes and standard progressions,” Baker continued. “I don’t say you shouldn’t blow in those modal veins—they’re interesting too—but I don’t think you should do it hour after hour, every night.”

As a recent repatriate, how did Baker feel about the increase in the influx of U.S. jazzmen into Europe?

“If I were a colored musician,” he answered, “with a halfway decent name, any name at all, that’s where I’d go to live, to get out of this mess over here, because you certainly don’t run into it over there.”

What was his reaction when he encountered the European philosophy that says only Negroes can play jazz really well?

“I never ran into that, myself, but I know that does exist. But I’m back, and I’m glad to be back, because all those people who say and feel that jazz is for the colored man only—I’m not going for that. And I’m going to do everything in my power to show them that that’s not right. There are many white musicians who can play. I’ll put them up against any colored musicians. The styles may be different—maybe it’s just a mater of taste—they certainly have got as much to say.”

When Baker arrived in New York, his plans were to live on a friend’s farm in Tonka Bay, Minnesota, and eventually play in a Minneapolis club that the friend was to open. It never happened because the terms of the contract were too one-sided, he claimed, adding: “He wasn’t promising me anything; I was promising him everything. He was just acting as a collection agency for all my money.”

Through composer Tadd Dameron, Baker became affiliated with Richard Carpenter, who used to manage Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, and soon he was on the jazz-club circuit. An engagement at the Village Vanguard fell through when a New York City cabaret card was granted Baker, but then quickly canceled.

However, Baker, the optimist, looks to the future with hope.

Of his early successes in the ’50s, he said, “I never really believed in that, and I never really believed that I deserved it. I felt that it was as though during that period people had been more or less just waiting for something new, and when it came about, they gave it more than it had due. I don’t believe at that time I deserved to win the DownBeat or the Metronome polls as the best trumpet player. I know I’m playing 10 times better now—and I’m not even mentioned in the polls.”

Whether or not he was the best trumpet player then, Baker’s playing had an emotional quality that went right to many listeners’ hearts. He still has that emotion in his work, those lyric qualities, and his self-expression has never been more assertive. If his music continues to be such a strong force within him, it won’t be long before his name is again on the poll lists. This, by itself, is never a complete measure, but it will be another reminder that Chet Baker has come back. DB