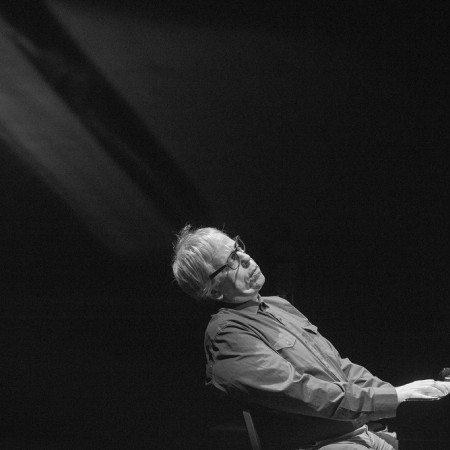

Kenny Werner

(Photo: Alessandra Freguja)On a warm June evening, a small crowd of clean-cut young adults stood in front of the Manhattan jazz club Iridium taking pictures. Dressed in identical red T-shirts that announced their affiliation to an out-of-town church choir group, the men and women took turns lining up in front of the modest marquee for a quick snapshot as a curious club employee looked on. A sidewalk sandwich board next to the front door announced that the Kenny Werner Trio with special guest Toots Thielemans would be performing two sets that night, and the tourists angled their cameras to ensure that all the information from this jazz tableau was included.

Sitting a few feet away from the club on a bench and watching the picture-taking drill with some amusement was the maestro himself, Werner. He walked past the visitors, entirely unrecognized, into a Chinese-Thai restaurant a few doors down from the club.

Few jazz aficionados would let Werner pass by without a quick greeting or a kind thank you for his artistry and illuminating insights on musicianship. Since making a name for himself at the piano in the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra in the mid-1980s, Werner has become one of the most important figures in the jazz world, acknowledged for his improvising and composing abilities. He has led several questing piano trios that have helped redraw the general map of the format’s range, and as an arranger/accompanist Werner’s work with vocalists, such as Betty Buckley, Joyce, Judy Niemack and Roseanna Vitro, has enlarged his reputation as a first-choice collaborator and tuneful pathfinder.

Music aside, Werner said that more often he is pegged and politely importuned as the author of Effortless Mastery: Liberating The Master Musician Within, his 1996 treatise on creative fulfillment and the role of the artist in the world. “It is unique in the realm of ‘how-to’ music books in that it doesn’t deal with scales and chord progressions,” said Matt Eve, president of Jamey Aebersold Jazz, which published Effortless Mastery. Eve notes that the book is tremendously popular, selling “tens of thousands” of copies over the years, “because it explores the reasons why musicians play, and why they have to play, while also showing how to shed hindrances and apprehensions.”

For the pianist, music exists primarily as a spiritual pursuit; he broadly addresses the themes that are extant in his life and art. “Whenever I play, I just want to get to the inner core,” he said. “We live in an increasingly culture-less society, in which art is not important, but I notice people do have an increasing need to know the meaning of their lives. A while back, I decided to focus on that hunger in myself, and let the notes flow from there, instead of worrying about art. When I started playing music, it wasn’t because I was thinking of becoming a jazz artist; it was because I loved to improvise. I didn’t grow up listening to records. I was too busy watching movies and television. But when I finally got hooked into jazz, it was because it seemed like a mystical path, not an art institution, and the greatest musicians of that day were philosophers and shamans—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock. They could alter your state, they had mystical properties that could take you beyond the mind.”

Werner emphasized that he develops his music from less of a technical angle, instead allowing deep creative impulses to guide his pursuits. “There’s this search for a force inside of you,” he said. “It’s part depression, and part questioning about the point of being an artist. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I began to wrestle with this, and I concluded that anything is cool if my mind is in a liberated state, and nothing is cool if my mind is caught up in a delusion. I began to focus on the spiritual passion of playing, made it an accentuated force and then was amazed to see the deep effect this playing had on audiences and listeners. On stage or in the studio, I’d be sitting in the middle of all this transformative energy and be so happy. I allowed myself to be in a state in which every note I played was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard. I was intoxicated.

“It is not about trying to give audiences more good art than bad art,” he continued. “For many years, I have been trying to satisfy a spiritual hunger, and that’s what is important, not the state of art. There is nothing worse than being an artist stuck in a single mind-set regarding how they should play.”

At Iridium, bassist Scott Colley and drummer Antonio Sánchez accompanied Werner. The trio warmed up with the standard “If I Should Lose You.” Werner’s wife, Lorraine, sat at a table in the back of the club. The couple lives in Upstate New York, near Kingston, and recently have dealt with the tragic death of their daughter and only child, Katheryn, in a 2006 car accident. In the trio’s set, right before Thielemans hit the stage, Werner introduced “Balloons,” which he told the audience was written in celebration of one of Katheryn’s birthdays. (One of Werner’s most famous compositions, “Uncovered Heart,” was written in honor of Katheryn’s birth in 1989.)

Thielemans, who has worked with Werner over the past dozen years, said that Werner offers him lessons on the bandstand every night. “He has his own style, and can play any music, with each song sounding great,” the harmonica player said. “His facility with harmony and his research in how we learn how to play music and derive enjoyment and emotion from playing have made a big impression on me. I love how he constructs different ideas while improvising.”

Werner is a born entertainer. “I wanted to sing as soon as I could walk and talk, then started dancing lessons at 3,” he said. The youngest of three sons, Werner said much of his musical ability is from his father, Jack, a produce wholesaler who played saxophone and had perfect pitch. The family moved from Brooklyn to Oceanside—out on Long Island—and at 7, Werner started playing piano, learning classical music and some show tunes. “I went to a friend’s birthday party, and his father started playing the piano and was immediately the center of attention,” he said. “That blew me away. My parents rented a piano for me, and I could play songs instantly by ear.”

Starting out at the Manhattan School of Music as a concert piano major, Werner left after a year and enrolled at the Berklee College of Music, where he fell in with the jazz musicians there, including Joe Lovano, Joey Baron and John Scofield. A turning point was an introduction to Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way, “which featured some of the greatest jazz soloists ever, and yet you aren’t conscious of their soloing on the record,” Werner said. This paradigm continues to be evident in Werner’s own quintet/sextet recordings, like Uncovered Heart and Paintings, the 2006 live date Democracy (Half Note) and last year’s Lawn Chair Society (Blue Note).