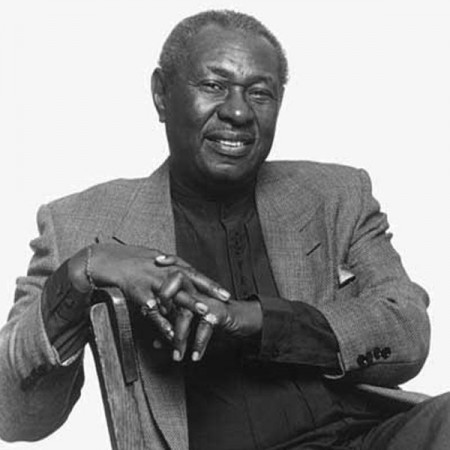

Freddy Cole (1931–2020)

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)Freddy Cole is a singer and a pianist. Outside of a couple of showpieces he was compelled to compose by way of acknowledging and freeing himself from the looming presence of his famous brother, Nat Cole (“I’m Not My Brother, I’m Me” and “He Was The King,” both on his Laserlight CD Live At Birdland West), he is neither a composer nor a lyricist. Cole specializes in bringing the work of other people to life.

This makes him something of an anachronism in a musical culture that for nearly 40 years has worshipped the notion of the “authentic voice” in its music—the idea that to be of value, true authenticity (as opposed to the illusions of show business) can only be achieved through a personal statement direct from performer to audience. For a singer alone to mouth another person’s words or music becomes an artifice of play acting, a facade concealing the great, business-driven music machine of Tin Pan Alley behind the curtain.

So where does this leave a performer like Cole? Sitting down with him recently in a Marriott bar in Schaumburg, Illinois, shortly before a sound check at the Schaumburg Prairie Center for the Arts, where was to perform that evening, I tried this little test. “Mr. Cole, can you name a single Top 40 song?”

Rolled eyes and laughter ensued. “Are you kidding?” Cole said, not the least big guilty, apologetic or embarrassed about his personal ignorance. “I wouldn’t be able to name a tune from the Top 100.”

“Well, don’t worry,” I told him. “Neither can anyone else over the age of consent.”

It wasn’t always that way, though, and Cole has been around long enough to remember when it was otherwise. When the Hit Parade, for instance, was a shared national commodity on radio and television, and everybody whistled more or less from the same page. And when network variety programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Perry Como Show and, yes, the fabled but brief Nat King Cole Show of 1956 routinely gave top singers with vast songbooks easy access to the entire nation. It’s not that there aren’t good new songs being written, Cole says. “I know a good song when I hear it. And if it’s good, I’m going to do it. The problem is that fewer are becoming standards.

“Everybody’s doing their own material. The singer-songwriters have pretty much been doing their thing for 30 or 40 years now. Nobody does anybody else’s songs, just their own. If a song can’t travel from one performer to another, it can’t travel from one audience to another, either. So they are confined. It’s hard for a tune to break out.”

Cole didn’t find jazz breaking out at last winter’s Grammy Awards, either, where he was nominated as Best Jazz Vocal Album for last year’s Telarc CD Merry Go Round. “It was my first experience,” he says like a man who had been abducted by aliens for three hours. “It made me so happy that I’m a jazz musician. It’s a 10-cent masquerade these days. You strike a match and everyone thinks they’re on stage. Women walking around half naked in designer dresses, for what? What does that have to do with music? But at least you have a chance when you’re competing in the jazz area because that’s about the music.”

Singer-songwriters and tacky music are not Cole’s problem, because he carries a formidable inventory of the real thing between his ears, which have been open and storing musical data for decades. They still are, and he knows where to look. His present Telarc CD, Rio De Janeiro Blue, is a case in point, a smart hybrid of Brazilian and American tunes in which the age of the tune, new or old, is just not an issue.

“I’m a Brazilian in my heart,” he says with some authority, having visited and played the country many times. One of his major successes was also in Brazil in 1977–’78, a record called I Loves You.

“I recorded it in Europe,” he says. “But it was featured on what is their equivalent of our soap operas, a novella. And this tune was on the biggest novella on Brazilian TV in the last 30 years, Dancing Days. It was used in the course of the story and as the theme as well. I even went to Brazil and performed on the show once. It was very exciting the first time I went there. I also had some mild success with another song called ‘For Once In My Life.’ I’ve been all over the country, not just Rio and São Paulo. I really love going there and have many friends there now. I love the language, and even sang one tune in Portuguese on the new CD.”

Then why not do an entire CD of Brazilian tunes?

“I’m at the point now where I’m receiving some notoriety for doing the things that I’ve been doing,” he explains. “And I didn’t think it would be appropriate to do the whole thing along that line, because I have other people who have been listening to me do a more standard book, and you don’t want to disappoint those people.

“I do a whole gamut of songs, and I never do a set program, unless it’s with a big orchestra. And even then I reserve the right to waive that and change directions. You never know how your audience is. Last week we were somewhere in Macon, Ga., and I saw what was happening by about my second or third song. I switched my whole repertoire into ‘Fascination,’ ‘Autumn Leaves,’ ‘Love Walked In’ and others. I went to Gershwin, Cole Porter, Kern, Ellington. You’ve got to know how to do these things. These were the songs they knew and these are people who spend a lot of money to come to a concert.”

I drop a 700-page book on the table called Reading Lyrics by Robert Gottlieb and Robert Kimball, a collection of more than 1,000 song lyrics spanning 1900–’75. Cole rises eagerly to the bait and leafs through the pages. The content seems as familiar to him as a personal diary, even though some of the titles he hasn’t done in years and perhaps never did. But that doesn’t mean he couldn’t.