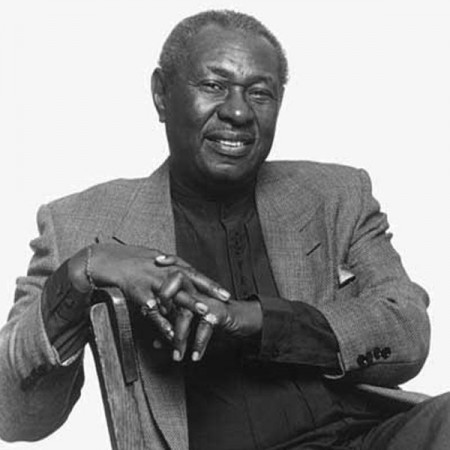

Freddy Cole (1931–2020)

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)“Here’s one,” he says. “‘Love Nest.’ You can swing it, too.” And he proceeds to do it, barely glancing at the words on the page as he does. But then he grew up with it as the theme song of George Burns and Gracie Allen. “Here’s another, ‘Give My Regards To Broadway,’ ‘If I Could Be With You,’ ‘After You’ve Gone,’ ‘Along Came Bill.’ This is a good book. Wow.”

He puts it aside for a moment and reflects on what he looks for in the music he performs and listens to. “I like to preach the theory of ‘What’s Wrong With The Melody?’” he says. “I tell students this all the time. I can tell them about phrasing and other nuances of performance, but unless they hear it they can’t know. I can tell them to listen to Gene Ammons or Johnny Hodges. Everyone wants to play like John Coltrane, but they can’t play a melody in a convincing way. John Coltrane could play a melody. John Coltrane knew the whole thing inside out before he got to do what he did. Students have to go listen to these other things. The trouble is, they want to start where Coltrane ended. But they don’t realize that Coltrane came from the melody. That’s true of all the great instrumentalists—Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Dizzy—they knew the song. The root to artistry is through the melody. Why do you think a composer spends all the time writing the song a certain way if he didn’t want it played that way?”

This is all very easy for Cole to say, of course, because he grew up with melodies in the air. They are second nature for him. He was born Lionel Fredrick Cole in Chicago on Oct. 15, 1931, the fifth of five children, three of them brothers. The oldest, as all the world knows, was Nat Cole, born 14 years earlier in 1917. (Freddy’s brother Ike, also a much admired singer-pianist, died in Sun Lake, Ariz., on April 22.)

His earliest memories are of the Cole Chicago home at 41st and Prairie, the piano that everyone learned to play, and Felson school around the corner, where he attended grammar school. Neither the home nor the school is still standing, and he rarely goes back to the old neighborhood during his frequent visits to Chicago. Around 4th grade, he says, the family moved 40 miles north to Waukegan, where he would spend his adolescence. As the post-war world was taking shape in 1946–’47, he became a star football player while about the same time his brother Nat was becoming a major star in popular music, with breakthrough hits such as “The Christmas Song” and “Nature Boy.”

“I was 16 in 1947,” Cole says, “and I can’t say I didn’t receive some accolades about having a famous brother. But most of my friends knew me as a good football and basketball player and being on the neighborhood teams. That Nat was getting famous really didn’t matter one iota. I saw my future in football. That was what I wanted to do. I was All-State football and basketball and had about 19 sports scholarships. Nat would come home and be real excited about my sports reputation.”

Had a sports career worked out, Cole’s life might have been very different. The color barriers in pro football were beginning to fall. Cole’s favorite team was the Cleveland Browns, which had Marion Motley and Otto Graham, whose father was Cole’s band teacher when he was in school in Waukegan. But it didn’t work out the way he expected.

“I never attended any university that had a football program,” he says. “I never got that far. I got a serious hand injury. The fingers on my left hand got hurt in some play, and the bone got infected. I was in the hospital a year and 11 months after my senior year in high school. That was it for me.

“But I could still play the piano. I’d played since I was 4 or 5 years old. And that was what amazed the doctors. I couldn’t even make a fist with the injured hand, but I had enough movement to play the piano. The diagnosis was tuberculosis arthritis, and I had several operations. But I never considered it a handicap.”

One reason Cole’s limitation never frustrated him was that, like his brother at that point, the piano functioned in equal partnership with his singing. He only had to take it so far. By age 15 he was playing his first small professional jobs around Waukegan and Chicago about the same time his brother was becoming a national figure. After his football injury, he turned totally to music, studied at Roosevelt University in Chicago and The Juilliard School in New York, and finally earned a master’s degree from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1956. Precisely when did his piano technique reach the point where it did what he needed it to do?

“Actually, that’s hard to say,” he muses. “You go along for so long and I’ve done so many facets in the business. I guess you wake up one day, and it’s like what Tiger Woods said recently. He was out on the driving range one day practicing. And all of the sudden he picked up his cell phone and called his coach to say, ‘I got it.’ A similar feeling came over me, but I don’t know exactly when. It was when I began to feel very comfortable with my peers and when the total acceptance was here from some of the name people in New York. People like Hank Jones or Tommy Flanagan would come to see me.”

Cole emphasizes that technique is very much wrapped up in one’s self-confidence. “Technically I know I can’t approach any of those pianists,” he goes on. “But what I can do is what I do best, and I know how to present it right.”

Not that he didn’t try, of course. In his teens Teddy Wilson still ruled over the stately basics of swing piano. Cole even studied with him briefly at Juilliard. Roland Hanna was another model.