Woody Shaw: The Complete Muse Sessions

(7 CDs)

If you are familiar with Mosaic, you know about our passion for jazz. Our bred-in-the-bones need to “get it right.” Our devotion to perfection in every detail. And when we are able, our conviction to expose the injustice of greatness overlooked through our limited edition box sets.

We are delighted to have a second opportunity to print the name “Woody Shaw” across a Mosaic collection, this time for his Muse jazz recordings spanning nearly his entire creative life. (Our box set #142 — his Complete Columbia Studio recordings which chronologically came in-between the Muse dates from the seventies and eighties — sold out long ago.)

Included in the new collection are the mid- to late-1970s recordings that established his musical identity, and saw him break through as an inspiring and influential musician and bandleader. Also included are the Muse sets from his return to the label from 1983 through 1987, where as a mature musician he displayed his range on the instrument and his appreciation for music of many jazz disciplines. The “Complete Muse” concept allows us also to present Woody’s very first set from 1965 when he was just 20 years old. Originally recorded for Blue Note but returned to Woody by Alfred Lion when the record company founder experienced remorse over selling his label, it became a Muse set years later.

Nine individual Muse albums are represented on our seven-CD limited edition box set. The collection includes many rare photographs from the time. The set was co-produced by Woody Shaw III, who has devoted his life to preserving the legacy of his father and that of his stepfather, Dexter Gordon. He also contributed the essay and track-by-track notes. As with all the Mosaic limited edition jazz collections whose masters we license, it will be available only for a short time and then never again in this form.

REVIEW

DownBeat / November 2013

★★★★

Trumpet’s Iron Man

by Kevin Whitehead

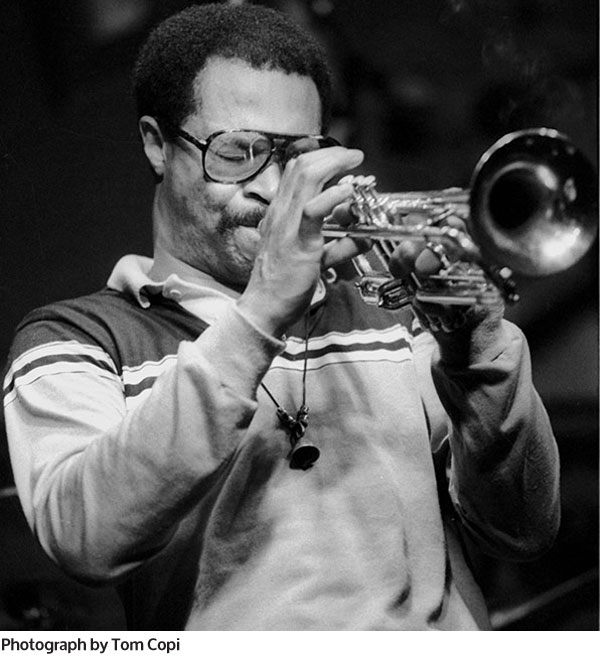

Woody Shaw started playing horn the month Clifford Brown died, and he wore seriously the mantle of “Next Trumpet Hero.” By the mid-’70s, this ferociously accomplished player with a surprisingly dark tone felt he’d earned it. Some blazing trumpeters blind you with the flame; Shaw’s sound was lightning deep in a thundercloud. His concept was partly shaped by early employers Eric Dolphy, with his dramatic wide intervals, and Larry Young, who schooled him on the versatility of pentatonics.

Leaping fourths were in vogue in the mid-’60s, and Shaw leapt in; the wider intervals he loved call for superhuman lip slurs. His December 1965 debut sessions as leader, with Joe Henderson on tenor and Joe Chambers on drums, show how quickly Woody caught on to what Miles Davis’ new quintet was up to, even as he cleared his own path. (You’d never mistake Shaw’s check-me-out chops for Davis.) One rhythm section has Young on piano and Ron Carter, showing how indispensable that bassist was to the modern Davis feel. The other date with the mighty Paul Chambers takes things back a step, even with Herbie Hancock on piano.

The Complete Muse Sessions (Mosaic MD7-255; 58:39/43:52/58:19/51:24/63:10/65:04/53:47 HHHH Four stars) is Shaw’s life in three acts: that belatedly issued 1965 session, five mid-’70s albums with more original tunes and three ’80s standards dates where the playing is impeccable but the conceptual fire has died down. Of the middle group, Little Red’s Fantasy for quintet and Love Dance for four horns and five rhythm have the crackle and fire typical of ’70s modal hard-bop—vital music written out of jazz history for a while, to make the arrival of ’80s Young Lions more compelling. (Shaw was Columbia’s great trumpet hope before Wynton Marsalis.)

Shaw liked a rich palette. A septet recorded live in 1976 spotlights billowing four-horn heads, and soft-edged harmonies over driving ostinatos and Louis Hayes’s explosive drums; the festival setting heightens excitement. The trumpeter floats on pianist Ronnie Mathews’ “Jean Marie,” his slowly building solo full of odd turns and topspin rhythms, climbing fourths and cascading descents, and a uniformly strong tone. Quick repeated notes are clearly articulated; cracked notes are rare enough to be shocking. He also had great taste in swinging sidefolk—like pianists Cedar Walton, Kenny Barron and Mulgrew Miller, drummers Eddie Moore, Victor Jones and Carl Allen and saxophonists Frank Foster, Billy Harper and Rene McLean.

His acclaimed Iron Man paid tribute to Dolphy, reviving two tunes they’d recorded together in 1963, including Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz.” It teamed him with new stars of the new music, Muhal Richard Abrams on piano (a rare sideman appearance), Arthur Blythe and/or Anthony Braxton on reeds. (Rare Mosaic credits gaffe: Braxton plays sopranino on “Song Of Songs,” not soprano.) The shifting terrain and jittery partners inspire Shaw’s daring as improviser and melodist. He sounded most striking in settings that amplified his individuality.

In the ’80s, Shaw went into fitful decline, owing to failing eyesight and drug-related woes, and an industry chasing younger talent. His confidence shaken, and with fewer recording opportunities (he told interviewer Marc Chenard), he stopped composing much, focusing on standards in his last years before his death in 1989 at the age of 44. But even when his life was erratic, he could still deliver when tape rolled, notably on Setting Standards for quartet, where he’s most exposed, and gets to the heart of the potentially glib “All The Way.” It’s no criticism of the sterling players involved to say the other soloists don’t grab you as Shaw does. The effect is diluted when he’s joined by other horns, fine as they are: The companion quintet sessions feature newcomer Kenny Garrett on alto, in audible thrall to Jackie McLean, and frequent trombone sidekick Steve Turre, whose own dark tone and iron chops make him a fine match.

Woody Shaw III’s notes are affectionate and informative; you can forgive him for not dwelling on his father’s tragic side, but he doesn’t ignore it. Braxton’s story of how Shaw put him at ease at the Iron Man session is heartwarming—a word rarely invoked, recalling Shaw’s too-short life. DB