Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

In Memoriam: Gordon Goodwin, 1954–2025

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

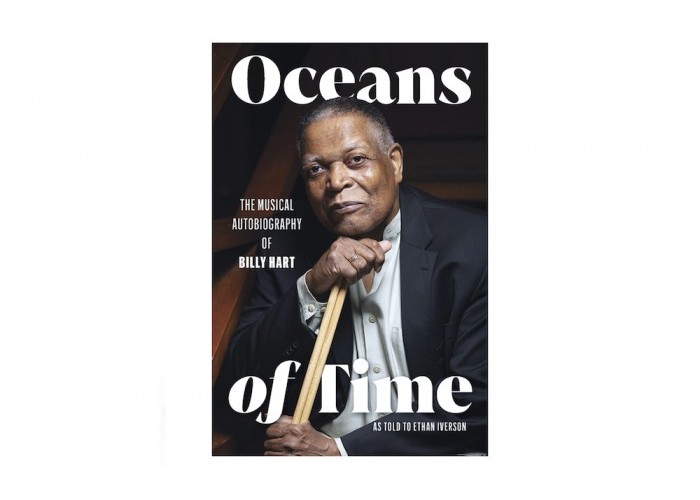

With over 600 recordings as a sideman and a dozen as a leader, Billy Hart offers his new autobiography.

(Photo: Courtesy Cymbal Press)The new memoir by master drummer and bandleader Billy Hart, who turns 85 later this month and is still busy touring and recording, is described as a “musical autobiography,” perhaps a signal to readers not to expect too many revelations about his personal life or spicy tales about his colleagues. It’s a promise that, happily, he doesn’t fully keep, even while he emphasizes the music, his famous collaborators and hard-won lessons learned on and off the bandstand.

Sometimes the stories in Oceans of Time (Cymbal Press) cross the line between the musical and the personal. Early on, Hart tells an anecdote about one of his most important mentors in his hometown of Washington, D.C., the peerless singer and pianist Shirley Horn, who taught the young drummer lessons in drama, patience, dynamics and the elasticity of time. In the book, he describes her as “somewhere between my first love and my grandmother.”

“After one set at a fancy supper club in Midtown with Shirley,” Hart recalls, “Sarah Vaughan and Betty Carter both told me I was playing too loud for a singer. So the next set, I pulled it back. Afterwards, Shirley came up to me and growled, ‘Billy, are you for me or against me?’

“Aw, Shirley,” he replied, “people have been telling me that I’ve been hitting too hard.”

“She looked me in the eyes and said, ‘Don’t tickle me.’ The implication was clear.”

The book was written with jazz pianist and writer Ethan Iverson, Hart’s musical partner since 2003. It’s based on dozens of interviews Iverson conducted with Hart over the years, including some previously published in Iverson’s award-winning jazz blog Do The Math.

Hart has recorded a dozen albums as a leader and performed as a sideman on over 600 recordings. One of the most versatile drummers in jazz history, it may be easier to list the major jazz figures of the last 65 years with whom Hart hasn’t played than those he has.

As a teenager growing up in Washington, D.C., his drumming, inspired by local drum heroes Harry “Stump” Saunders and Ben Dixon, was already good enough to accompany the R&B luminaries who came to town, including Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, The Isley Brothers, Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, Smokey Robinson and Aretha Franklin when she was still singing jazz. After playing with Horn, with whom he recorded the classic album Lazy Afternoon, he toured with Jimmy Smith, Wes Montgomery and Eddie Harris.

Major associations followed with more icons: Pharoah Sanders, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock and Stan Getz. His prolific work as a sideman included gigs with Miles Davis (that’s him on On The Corner and Big Fun), nine years on-and-off with Charles Lloyd and collaborations with Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Jones, Freddie Hubbard, Joe Henderson, Benny Golson, Art Farmer, Clark Terry and Oscar Peterson. He even played bossa nova with João Gilberto, who taught him how to play the partido alto and other Brazilian rhythms (recorded on two albums, The Best Of Two Worlds and Getz/Gilberto ’76).

Hart was a founding member of Hancock’s group Mwandishi (the source of his Swahili name, Jabali) and founded a working cooperative with Dave Liebman, Richie Beirach and Ron McClure called Quest. He still plays high-energy post-bop with The Cookers and his own quartet. He has taught at Oberlin Conservatory of Music, New England Conservatory of Music and Western Michigan University since the early 1990s.

Rich with anecdotes about some of the music’s greatest players, the book also serves as a thoughtful history of jazz drumming since the bebop revolution. It is also a chronicle of the ups and downs of Hart’s own career, a compendium of wisdom about jazz and life, and a book about how jazz works, from nuts and bolts to musings on the music’s history and deeper meanings. Beginning with an insightful essay on the meaning of swing, it includes a summary of Hart’s teachings about jazz, an annotated Hart discography and a collection of tributes to Hart from an impressive list of contemporary jazz drummers.

In an early chapter, Hart recounts the experience, shortly after arriving in New York City, of auditioning for Milt Jackson, the legendary vibraphonist from the Modern Jazz Quartet, that turned into a pivotal moment in the young musician’s development. He thought he knew Jackson because he had the MJQ records.

“How was I to know that (Jackson) often disagreed conceptually with John Lewis and the delicate aesthetic of MJQ? I tried to play like I would have played with the MJQ, and luckily word got back to me that Milt had said, ‘Billy Hart! I never heard such a drummer that didn’t play nothin’. I thought the motherfucker was dead.’” Hart’s conclusion: “It dawned on me that these great New York musicians wanted more from a drummer than subservience. They definitely wanted your opinion.”

During a joint video-chat from Hart’s home in Montclair, New Jersey, Iverson recalled first meeting Hart 30 years ago. “I was a fan. When I started collecting records, I really liked Billy’s playing, and I would buy a record just because his name was on it. There was a trombonist who called me for a gig, and one of the drummers ended up being Billy Hart. From the first moment I played with him, I thought, this is what I need. There’s a lot I don’t know, and I bet Billy can help me. So I started pursuing him.”

Iverson became a member of the Billy Hart Quartet, along with saxophonist Mark Turner and bassist Ben Street. He has spent years hearing, and eventually recording, Hart’s stories. The partners had intended to tour during Hart’s 80th birthday year, but their plans were dashed by the COVID pandemic. Instead, Iverson began a series of Zoom conversations with Hart that became the book project.

Hart’s career has been described as spanning the worlds of traditional, mainstream jazz and the avant-garde, but he shies away from claiming to be “influential” on the styles of other drummers. “There are a lot of people who are more influential than I am,” he demurs.

Iverson rejects that notion: “Let the record show that a lot of the drummers at the end of the book talk about how impressed they were by the way you could play with anybody in any situation. In fact, Allison Miller credits you with showing her that you could play any style and still work, because people advised that you should play just one style and that’s how you get a career. She watched you and (concluded), ‘I’ll just do whatever I want, because that’s what Billy Hart does.’”

In their work together in Hart’s quartet, Hart observes that the two sometimes argue about repertoire, and that when they do, Hart often wants to be more “creative,” and Iverson wants to swing more. Which leads one to wonder, is Iverson the more tradition-minded one and Hart the more experimental one?

Pondering this for a minute, Hart replies, Yoda-like, “I think, in certain ways, being traditional is experimental.”

“Another Zen koan from the master,” Iverson says. DB

Goodwin was one of the most acclaimed, successful and influential jazz musicians of his generation.

Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…