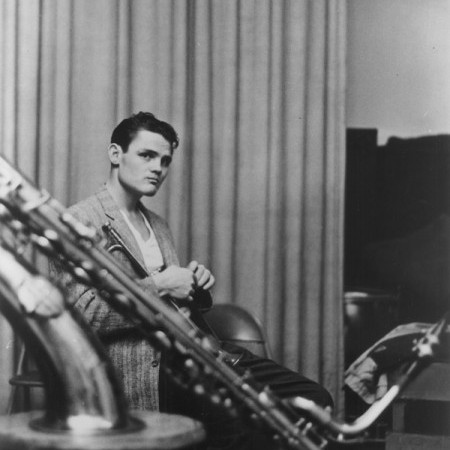

Chet Baker (1929–1988)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)In the middle 1950s, Chet Baker was the young Lochinvar out of the West, the fair-haired boy of critics and laymen alike, riding in on his golden trumpet. Rising to prominence with Gerry Mulligan’s pianoless quartet, as the West Coast jazz movement began its popular sway, he won the New Star award in DownBeat’s first International Jazz Critics Poll in 1953. Then Baker formed his own quartet and went on to win both the DownBeat and Metronome readers’ polls for the next two years.

Now, approximately 11 years after the first flush of success, he has returned to the United States from a five-year European odyssey that included the sweet smell of success—but only in whiffs. More often the odor was of creosote in jail.

From September 1955 to April 1956, Baker toured Iceland, England and the Continent with a quartet. During that period his pianist, Dick Twardzik, died in Paris of an overdose of heroin. Baker came back to the U.S. As he tells it:

“When I came home, I started using drugs. I got busted several times, went to the federal hospital in Lexington [Kentucky]—then I got busted in New York and did four months on Riker’s Island, and I decided to leave the United States for a while.”

At the end of July 1959, Baker departed for Italy alone and upon his arrival formed a quartet with local musicians. But if he had expected to find a more lenient attitude toward drug use, he soon found he was mistaken.

For 17 months he languished in an Italian jail. While he was serving his sentence, a film company from Rome approached him about bringing his life story to the screen. Baker wrote the script, and the company worked out several different versions of it but “couldn’t make up their minds,” according to Baker.

By the time he was released from prison, the prospect of his life story on film, directed by a top-flight man—Dino DeLaurentis had been in at the beginning of the idea—had evaporated. But another opportunity presented itself almost immediately. A good friend of Baker’s had become owner of the Olympia, the largest night club in Milan.

“He had a small room there that they didn’t use,” Baker related, “and he let me have that. He gave me a waiter and a bartender and put a sign outside: CHET BAKER CLUB. It was very elegant—plush, upholstered chairs, wall-to-wall carpeting, columns in the middle of the room, beautiful little bandstand, velvet drapes on the walls, the lighting was beautiful and it seated about 80 people comfortably.”

Baker played there for a short time, but the official opening never took place.

“I went to play a concert in Munich,” Baker explained, “and I had trouble there. Nothing happened, but there was a lot of publicity in the newspapers, and when I got back to the Italian border, they wouldn’t let me in. I had signed a contract with RCA Italiana and I lost that. And they tied a lot of my money up—about 3,000,000 lira.”

Baker had made some recording for the firm and said he was to do two more albums, but these never came to pass. When he was refused re-entry to Italy, Baker went to Paris, where he worked at the Blue Note for three months.

Then he received an offer to do a movie in England with Susan Hayward and spent nine months there. “I was trying to wait out the one-year waiting period, so I could join the union and work in England,” he said, “but I had trouble there and was deported.

“The movie was originally supposed to be called Summer Flight, but I think they changed the name to Stolen Hours or something. Susan Hayward, in the story, is ill, and she’s going to die, and she throws a big party, which most of the story is around. I’m the leader of the band at the party. I did a lot of the sound track for the movie, and I believe the opening shot is a close-up right on the bell of my horn.”

After England had sent him back to France, Baker worked at Paris’ Chat Qui Peche for about eight months. It was here he teamed up with Melih Gürel, a Turkish-French horn player who is a graduate of the Ankara Music Conservatory. From there, Baker went to the Club Jamboree in Barcelona, Spain, as a single.

“It was a pitiful rhythm section,” Baker said. “Kenny Drew had been there just before me, and he had walked out on the job and told them they shouldn’t even be playing. He gave them a terrible complex, so when I got there, they were really scared to death.”

After a month in Spain, Baker returned to France, where he received an offer to play at the Blue Note in Berlin. He played there one night and promptly was arrested. He spent 40 days in a German hospital and then was deported, but this time it was back to the U.S. on March 3, 1964.

Why, when there are several other musician-addicts in Europe, did a pattern of harassment seem to follow Baker?

“I don’t know,” he said. “It just seemed like field day for the police department whenever Chet Baker came to town. It seemed to be a tie-up between the police department and the newspapers—the publicity bit—because I was always very cool. I never bothered anybody. I never sold any drugs to anybody. Everything I did was for myself.

“I really believe it’s the fault of the journalists and the newspapers in those countries. For instance, you probably read about them finding me in a filling station. Well, the true story about that is that at that time I was in a clinic. I had put myself in a clinic in Lucca [Italy], and I was working in Viareggio ... the doctor would take me to work and bring me home.

“One day, I had to go into Viareggio in the afternoon—for a contract or to have some pictures taken—so he gave me the medicine I needed for that day. I had a little Fiat that I rented and I started to get on the Autostrada—which was about a 30-minute ride—and I wasn’t feeling very good, so I decided to stop in this gas station and make an injection before I got on the Autostrada, because you can’t stop. So, I went in there—I had stopped there many times before—and I went into the men’s room, but I had a lot of difficulty making the injection. I was in there about 35 minutes, and there was a knock on the door. I had just finished and put everything away. It was the police. They said, ‘Come with us.’ I went to the police station, and they called the doctor. In 15 minutes I was gone.

“But that night when the newspapers came out, they said that Chet Baker had been found unconscious in the toilet of a filling station, that there was blood everywhere, that the police had to break in the door—and none of this was true. Naturally, when the people in the tribunal, the courts, read these things, they probably think, ‘The man is completely insane.’