Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

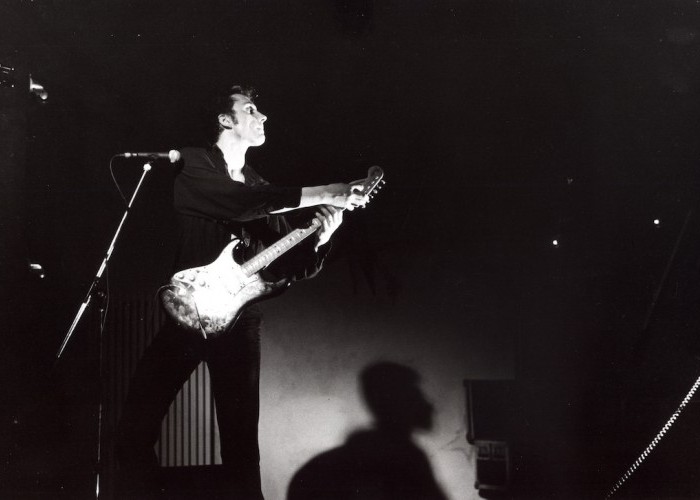

Caspar Brötzmann performs at Berlin’s SO36 during a tour for Black Axis. The guitarist’s work with his trio, Massaker, is being reissued by Southern Lord Recordings, which also will release a record by a new Brötzmann project, Bass Totem, in 2020.

(Photo: Frank Schröder)Among the most exciting and forward-thinking albums to come out early in 2019 are a pair of recordings made decades ago: Caspar Brötzmann Massaker’s The Tribe (1988) and Black Axis (1989). The albums are just the first of the band’s five-LP catalog set to be reissued throughout 2019 and 2020 by Southern Lord Records. A special-edition box set collecting the releases is to follow.

Formed in Germany during the mid-’80s, Caspar Brötzmann Massaker arguably was one of the most electrifying power trios in the world. While its music had roots in hard rock and metal, its raw, adventurous and complex sounds seemed to exist beyond genre or convention—alchemizing elements of avant-garde composition, far-reaching improvisation and tribal rhythms into a vivid, noisy squall.

At the helm was vocalist and guitarist Caspar Brötzmann, whose ferocious, dynamic playing—for example, throttling on the headstock and plucking the strings up near the tuning pegs of his guitar to build layers of atmosphere and texture—has made him a cult figure among fans of challenging, tension-heavy music, as well as a much sought-after musical collaborator. In addition to Massaker, he’s worked with Helmet’s Paige Hamilton, Einstürzende Neubauten’s F.M. Einheit and more recently with Zu’s Massimo Pupillo. And in 1990, the guitarist released an album with his father, free-jazz reedist Peter Brötzmann, titled Last Home.

Brötzmann’s distinctive guitar style stems more from a lifetime of working to forge an artistic identity than sheer technical mastery. “The simple truth is that I tried, in the ’70s, to find a way to play guitar like me and not to be a copy of Hendrix, my father or anyone else,” he said.

In several interviews, he’s discussed how his guitar and amplifiers merely are the tools of his self-expression, and listening to his music it’s easy to get the sense that no matter which instrument or creative medium he gravitated toward, he’d approach it with equal imagination and fervor.

Born in 1962, Brötzmann took to the guitar while growing up in West Germany, where he was particularly drawn to the myriad rhythms and sounds he heard in his everyday life—especially from within his grandfather’s blacksmithing shop and the rumbling steam locomotives that ran near his home.

“My grandpa was a blacksmith, sometimes like an artist blacksmith,” Brötzmann said. “His masterpiece was a handmade black iron rose made with ornate details. His workshop was very impressive. Heat and steel, and in his really rough and strong hands, he could pick up a glowing piece of coal.”

Gradually, these industrial influences began seeping into the younger Brötzmann’s music.

By the time he launched Massaker in West Berlin, the city was a hub for experimental, industrial, punk and electronic artists, as well as for social and political unrest. (“If hundreds of policemen hit their protection shields with their batons, you never will forget [the sound].”) With Massaker, Brötzmann found an outlet to explore these tensions and his observations about humanity, while fusing elements of improvisation and composition—though hearing any sort of pop-centric verse-chorus-verse, is a fraught proposition. He describes the approach as “freedom under a high-volume level. A lot of rock and blues bands did the same: Play jam sessions, have fun and start new, if the music goes boring. I did the same, just later and without the traditional blues structures.”

Where some bands rehash similar ideas throughout their lifespan, each Massaker album presents something new, and repeat listenings only seem to reveal more secrets, giving each recording a timeless feel. “I guess that has something to do with to being true to yourself, finding the power inside of you, and playing what you can see and feel,” Brötzmann said, discussing the quality of those decades’ old recordings. “If there’s nothing new, I guess it’s better for me to be quiet. I do not want to play one song my whole life.”

Following its fifth album, 1995’s Home, Massaker went dormant in the studio, and after a final show in 2000, the band didn’t play again for a decade before reuniting for a string of shows, including an appearance at the 2011 Roadburn Festival, which was curated by drone stalwarts Sunn O)))’s Greg Anderson and Stephen O’Malley. Anderson also runs Southern Lord, and following the Massaker reissues and box set, the label is planning to release in 2020 new material from the musician’s latest project, Bass Totem (a title of a song on Massaker’s third album, 1992’s Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore). “I am not using the name Massaker anymore. That is over. In these times of terror, it is impossible for me to play under this name Massaker again,” Brötzmann said.

Bass Totem is still a work in progress, so Brotzmann understandably is keeping close guard of some of the project details for now. But as its name suggests listeners can expect a lot of bass guitar. “There are solo songs, songs with guest musicians, and a band trio with drums and two basses, maybe more musicians,” he said.

No matter where the new music takes him (or vice versa), there are some elements of Brötzmann’s process that forever will remain the same. “My work is really simple and has a lot to do with praxis,” he said. “Plug the guitar in and play, track yourself and work out the good moments—you never know how they’ll find you. Build up an intro, a few song parts, and a refrain, and open the improvisation with a guitar solo. That is, and was, my freedom.” DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…