Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

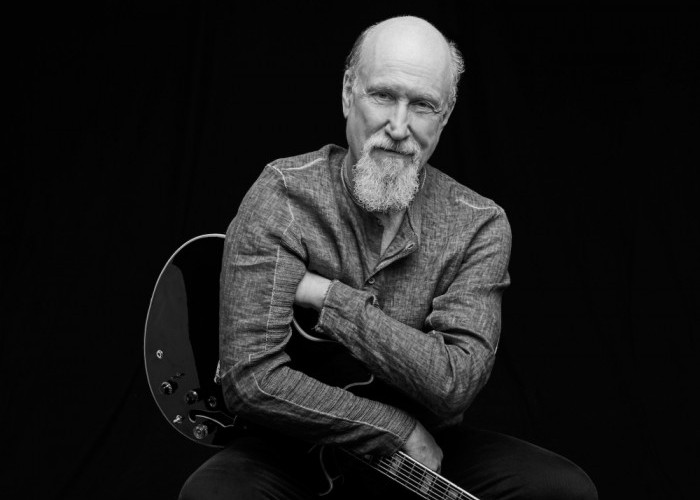

For his latest album, Combo 66, guitarist John Scofield enlisted drummer Bill Stewart, pianist/organist Gerald Clayton and bassist Vicente Archer.

(Photo: Nick Suttle)It’s November 1982, and 30-year-old John Scofield is in Cleveland to audition for Miles Davis’ group. The Man With The Horn was released the previous year and guitarist Mike Stern is still on the bandstand, but Davis has heard about a hot-shot guitarist from Connecticut.

“Miles [would] always bring in guys—he was notorious for doing this,” Scofield recalled over sushi in Brooklyn.

“I was unbelievably nervous,” he continued. “It’s winter in Cleveland—it’s freezing cold. Miles was gigging that night at the Front Row Theater. I show up, got my guitar with me. Road manager says, ‘Go in that room.’ Miles is there, all dressed for the gig. He says, ‘Take your guitar out.’ My guitar is all cold from the cab and my hands are cold, too, right? Miles goes, ‘Play something.’ I’m like, ‘Play by myself on my cold electric guitar with no amp?’ Miles is checking me out, looking at me. Then, stupidly, I played ‘Nardis.’ It’s a Miles tune. He looks at me and says in his raspy voice, ‘You don’t sound so good.’ Then he went and played the gig. I felt like shit. Later [that evening], Miles said, ‘Listen to the band, then you’ll start tomorrow night.’ So, I listened to the band and he paid me for the gig, though I didn’t play. Then I started playing in the band and I guess I didn’t sound like shit, because he went for it.”

Scofield went on to work with Davis for about two years, recording a few albums with the iconic trumpeter: Star People (1983), Decoy (1984) and You’re Under Arrest (1985), for which he composed the title track.

Today, Scofield continues to compose prolifically, and lessons learned during his time with Davis have proven invaluable in his ongoing experience as a bandleader. He penned all of the material for Combo 66 (Verve), a new album that celebrates the guitarist’s 66th birthday. Returning to his venerable hard-bop quartet format, with longtime collaborator Bill Stewart on drums joined by pianist/organist Gerald Clayton and upright bassist Vicente Archer, Combo 66 combines blues- and country-inspired melodies with fantastic, free-thinking guitar solos. As Clayton keeps the harmonic structure intact, Scofield burns.

“When I play with really good players who are like-minded, it just makes me play better,” Scofield said. “Gerald inspires me. He’s been knocking me out since I first heard him [when he was] in high school, and he only gets better. Guitar and piano are both percussive and chordal, so sometimes they can cancel each other out. But that never happens with Gerald: He just enhances the music, and his solos are about as good as you can get. And Vicente loves to support the music in the bottom end. So many bass players nowadays think they must play a whole lot. Vicente loves the function of the bass. Just like all the greats, Paul Chambers and Ron Carter, and Vicente’s also an incredible soloist.”

Scofield reserves special praise for Stewart, one of the hardest-swinging if enigmatic drummers in jazz.

“A lot of drummers, you bring them a tune and they don’t know what to do,” Scofield said. “They know the established grooves, but they can’t find something of their own that works with it. Bill can always do that. He’s a genius. Things are easy for Bill that are difficult for the average drummer. He can just conceive of stuff beyond what’s written on the page. That is really far-out. And, his sense of time: Bill knows how to make the music feel good without pushing it.”

The tunes on Combo 66 roll off Scofield’s guitar and into the listener’s brain instantly—and stay there. A sturdy sense of melody and style can be heard throughout the guitarist’s leader discography, which dates back to 1977 and has earned him three Grammy awards.

Kernels of the blues, bop and country inform every corner of Combo 66, served on a bed of dry, surging swing. “Can’t Dance” pulses gently, with Stewart’s tipping ride cymbal driving Sco’s equally touching and rustic melody, the second half played in unison with Clayton’s percolating organ, Archer goading the groove down below. Dark and moody, Scofield’s “Combo Theme” recalls a Henry Mancini soundtrack missive. “Icons At The Fair” soars through stop-time, curling melodic phrases and a see-sawing, tumbling arrangement. The country-fried “Dang Swing” bucks and jerks like a bronco. “I’m Sleeping In,” titled, as are most of his tunes, by his wife and manager, Susan Scofield, is a fine example of his skill at composing a memorable, if left-of-center, ballad.

“I wrote all these tunes around my 66th birthday,” Scofield said. “I’d go to my studio and think of what type of tune I’d like to try and write, medium tempo or a ballad or something funky or a bebop tune, and then I’d improvise into my iPhone. Sometimes, the first thing that comes out can be the germ of a tune. I’ll use that for the first bar or first two bars. Then comes the work of getting the next phrase: You just build it phrase by phrase. Sometimes, it comes rather quickly, and other times I’ll take an idea that I had 15 years ago and make that into a tune.

“The song ‘Combo Theme’ is challenging, for sure,” he continued. “But I’m trying to write something poignant and simple. ‘New Waltzo’ has a little bit more writing in it than the others; that’s got a little more composition to it. ‘Dang Country’ is just a blues. It’s so simple. It’s like a country guitar lick over straightahead blues-jazz. I just can’t get away from trying to play ‘the shit’: bebop.”

Freed by Clayton’s harmonic bedrock, Scofield plays some of the most dynamic, melodic and downright nasty solos he’s ever committed to disc. Is he engaged in storytelling or simply reworking the melody?

“People can get hung up on trying to tell a story—it’s notes, it’s freaking music!” he exclaimed. “But one thing that helps if you’re soloing is to use variety, so you’re not just hammering the same thing every chorus. And to get variety, you have to use melody, right? I wish I used more harmonic stuff, more chordal stuff in my solos, and I want to develop that more. But you have to play melody and find melodic phrases. Take Lester Young: He played such beautiful melodies, but he swung so hard. Paul Desmond does that, too, and Chet Baker. There are certain improvisers over the years who play a little bit more melodically and that doesn’t mean that they were wimpy. Miles Davis could burn as hard as anybody, but he also played with melody. And that’s telling the story.”

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…