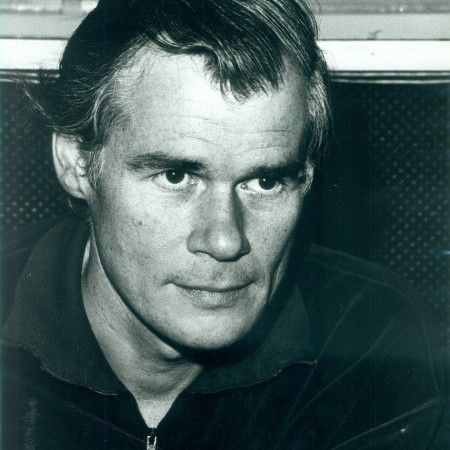

Galt MacDermot (1928–2018)

(Photo: Dagmar/DownBeat Archives)Long before he wrote the scores for Hair and Two Gentlemen of Verona, Galt MacDermot had made his mark in popular music. His “African Waltz” had been a big hit in Europe when first recorded by the English bandleader Johnny Dankworth, and became even bigger when Cannonball Adderley turned his attention to it here. Yet this brought more fame to the performers than to the composer, and between that time and the international success of Hair, MacDermot worked with steady determination but scant recognition.

When he moved to New York in 1964, a dozen or more of his compositions had been recorded by Denis Preston, a London producer for whom I had made a series of albums by American jazz musicians. Then as now, there was profound discontent in Europe with the kind of jazz American companies preferred to record and, more especially, promote. MacDermot and I soon found that we shared a common interest—Duke Ellington. He came to Ellington’s record dates with me, and I made some very inadequate attempts to assist him in what is so accurately described as “the music business.”

Success has not changed him in the least. He still dresses with careless informality and, although he claims to own one, he is rarely seen behind a tie. He still lives with his family on Staten Island, in the same house he originally moved into; the only difference being that he now owns another home next door and uses it as a studio. Calm, good-looking, humorous, unassertive, modest in speech and manner, but firm in his musical beliefs, he is totally unlike the kind of character one expects to encounter on Broadway. Seven years after I first met him, I learned indirectly that not only had his father been Canadian High Commissioner to South Africa, but also Ambassador to both Greece and Israel.

“African Waltz” was originally part of an operatic score MacDermot composed, more or less as an exercise on the foundation of Joyce Cary’s African novel, Mister Johnson. The success of this instrumental was so encouraging that he decided to devote more time to composing and less to performing. What was, for him, a significant breakthrough, nevertheless remained puzzling.

“I’d been trying to peddle my music for years,” he said, “and I didn’t know why this worked. It seemed like a fluke. ‘Are they kidding me?’ I asked myself. ‘Why do they buy the record?’ I honestly believe that people like what I call a jazz feeling, but the difficulty is to get it into a form they can accept. They don’t really like jazz as jazz anymore, because it has too many overtones of time and style. But ‘African Waltz’ had a certain thing, a black feel, and I figured maybe that was it.

“I had been in South Africa four years, and I really soaked up African music. That’s what Hair is—African music. I wrote a lot of pseudo-African tunes while I was down there, some of which, like ‘Chaka’ and ‘Ma Africa,’ were later recorded in London. It sometimes seems as though everything I learned about music I learned either from Ellington or from the Africans, the way they do music. When Hair went to Broadway, I didn’t think the people were going to be able to stand all that relentless rhythm. And I don’t know what made the show a success, but I think Gerry Ragni’s and Jim Rado’s approach—to the flag, dope, sex—was really extraordinary. If you saw the show early, when it was really fresh, everything seemed crazy, odd and different from what you’d run into before.”

MacDermot was born and raised in Canada, but when his father was appointed High Commissioner to South Africa, he had enrolled at the University of Capetown, where he majored and got his degree in music. When he returned to Canada, after marrying a Dutch-born music student, he had a living to earn. One of his first jobs was in a church, the income from which he characteristically supplemented by playing in a dancehall. How did he feel about the impact of gospel music on contemporary American music?

“I played organ for seven years in that Baptist church in Montreal, so I know all about their tunes. Of course, we played them pretty straight up there! They’re so sweet, and the sentiment is always the same—optimistic, clean, and humorless. Even black gospel music doesn’t have all the elements, unlike jazz which had the soul, and the fervor—and wasn’t without humor.

“Quite a lot of jazz came from the practices of the gospel groups—that sense of soloing against the beat, of pulling back and getting ahead. Sometimes on the radio, in switching around, I’d hear what sounded like a fantastic trumpet note, and it would turn out to be Aretha Franklin or somebody. I like gospel music, but the trouble is that it gets boring. It has that religious overtone, and it never gets away from that because of the songs they’re doing. It’s not that the performers can’t do anything else. We had a couple of singers in Hair who had come out of the church. It was rather like meeting Catholics who have dropped their religion. They never really lose it, but always have the idea that Satan is looking over their shoulder, and it affects their freedom. They’re not as free. And, again, I think that was what was so fantastic about jazz; the freedom of it.”

Wasn’t Aretha Franklin, perhaps, the exception that proved the rule, the artist who could escape the confines?

“Aretha escaped them somehow, managed to free herself from the inhibition. She sings nice songs, not really—or not only—gospel songs. You can always hear the gospel background, and there’s nothing wrong with that in itself. What’s wrong is the limitation of sentiment.”

The transitions from jazz to rhythm and blues, and then to rock, had seemed to result in a far less sensitive rhythmic motivation. What about swing, that emphasis or that impulse?

“During the ’50s, in Montreal, I heard black groups that came from the U.S., and they were practicing early forms of rock ’n’ roll. They didn’t swing in the way that we know, but occasionally they would. They’d get high as kites and every once in a while they’d start to swing. They were in their 20s, and I thought I heard the beginning of a new jazz in what they were doing. I’d go down to the Newport Jazz Festival and wonder why they didn’t get some of the groups I heard in Montreal. Then the whole thing died. In the best of those groups, their trumpet players weren’t really soloing. They were concentrating on the beat, all the time, and maybe that’s why it didn’t get creative.

“But for a while I found more of the feeling that had been in jazz in rock ’n’ roll. Today—and I’ve been listening to the radio a bit—there’s nothing. I mean, I can’t hear anything. It just isn’t as inventive as it was. In any case, there’s a basic difference between its aim and that of jazz. Jazz tries to create a tension, a dramatic tension, like Cootie Williams does. Rock ’n’ roll is trying to hit it right on, the way Africans do. It’s all right on in African music, where everybody’s doing a different rhythm around a fundamental rhythm, and the conflict makes the kind of tension you’ve got in jazz. But it’s not like the way Erroll Garner puts the tension between his hands, nor the way a jazzman will do it against a rhythm section. That isn’t African. I don’t know where that came from; it’s more American.

“When you hear rock ’n’ roll groups nowadays playing what is called a fusion between jazz and rock, all you are getting is people playing the changes, and there’s a tension, none of that drama, and none of the complexity of African music. There’s not even the enthusiasm of rock groups when they used to get on one little note and milk it for all it was worth. I loved that.”

After “African Waltz” and a couple of years in London, MacDermot decided to try New York, where music publishers and recording company executives were baffled by him.

“There was,” his friend Nat Shapiro said, “no pre-existing slot in which they could conceivably deposit this musical maverick. Undeterred, but with his sense of humor intact and his imagination as free as ever, Galt continued to try to interest anyone—anyone at all—in his music, while earning his living playing rock ’n’ roll piano at recording sessions.”