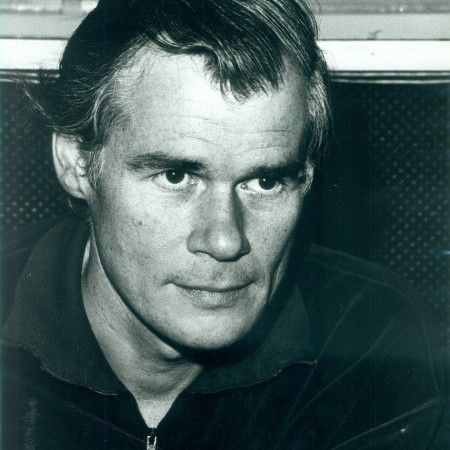

Galt MacDermot (1928–2018)

(Photo: Dagmar/DownBeat Archives)Shapiro’s office was one of the places he had developed a habit of dropping into, “looking for things to do” and the opportunity for intelligent conversation. How had that come about?

“Most of the people you ran into around New York, you just couldn’t talk to ’em. I discovered Nat [Shapiro] had written [Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya] with Nat Hentoff, and when we began to talk about Ellington, he turned out to be a real jazz fan. Then we got into it, and I played him a few things I’d written, and he was interested.”

Early in 1967 Shapiro gave him the script of Hair to read and introduced him to its authors, Gerry Ragni and Jim Rado. Enthused, MacDermot set off for his Staten Island home to return 48 hours later with eight completed songs.

“They wanted a rock ’n’ roll score. They knew the Rolling Stones, whom I didn’t like at all, and the Beatles, whom I did like. They didn’t like country music, which I love, and they weren’t too familiar with rhythm and blues. I tried to get more of what I liked into the score, even if it didn’t always apply to city life. Then a lot of the songs in Hair were imitations of what pop groups were doing. The parodying of some of the popular styles was one of its humorous aspects. But at the same time, I wanted to get a genuine feeling—a jazz feeling, actually—because the freedom of the show was what I have always considered jazz to be about. Exuberance, that is, and tension, and a kind of suffering. But I didn’t want it to be a swing thing. I wanted to make it with the kind of rhythms you hear now.

“It came off better than I had hoped. Nobody was keener than I to do it, but nobody could convince me it would work. It was really wacky. Oddly enough, the only tune I rewrote was “Aquarius.” They handed me the lyrics, and I had just a day to write it, so I came up with a very pretentious, Rodgers and Hammerstein type song. We all knew it wasn’t right, but we managed to get over the audition, and by then I was already thinking of a different kind of feeling for it. The approach to the words had been wrong. The words were what the kids were saying then, and since they had to sing them, you couldn’t laugh at the words. I think the reason the record hit was in the tail end of it: ‘Let the sunshine in.’”

MacDermot still loves to play. He played piano in the Hair band for a time, and he occasionally does concerts with three of its members, mainly for kicks. These musicians are Idris Muhammad, a brilliant modern drummer from New Orleans who has been extensively recorded; Jimmy Lewis, a bassist who was with Count Basie in the early ’50s; and Charlie Brown, a relative youngster who plays beautiful country guitar. Because all four knew it, and because it is what their audiences want, their repertoire mostly consists of the Hair music. MacDermot does not consider himself a jazz musician, but he enjoys those times when the four of them, with their differences of conception, achieve what is primarily a jazz blend.

For his other great success, Two Gentlemen of Verona, he also played piano at first in the pit, and he remains very enthusiastic about the 14-piece band assembled for the show. It included such well-known musicians as Thad Jones, Dicky Harris, Everett Barksdale, Billy Nichols and Bernard “Pretty” Purdie, and their potential can be heard throughout the original cast album, not least in the two instrumental tracks on the final side, “Dragon’s Music” and “Where’s North?” Playing, however, tends to affect MacDermot’s ability to write.

“One reason is because I like a lot of sleep. I normally go to bed around 9:30 and get up about 7:30. Duke Ellington seems to be able to play and write. I suppose if I established a real, life-long habit of doing it, but I put all the music into the playing, and then after a time I find I get a little stale on the tunes. I have to find some kind of happy medium between playing and writing.

“I go to hear Ellington whenever I can, and the last time he was at the Rainbow Grill I really heard some music coming from him and his guys. The Chinese piece from the Afro-Eurasian Eclipse was very interesting. But what impressed me most was Ellington’s own playing, because he was finding things that night. Then they did a number with just the three tenor saxophones, and they all got into a mish-mash at the end. The rhythm section cut out and there were those three guys blowing away, and Duke egging them on. They didn’t take it seriously, but it was an example of an idea evolving from a situation. I know of no one other than Duke who presents jazz in such a successful way. He has been doing it for years, and his personality carries it. He’s simply the best. Although there’s no question about that, it wouldn’t necessarily ensure that he would always be able to sell his music. Yet he has managed to do so. I’ve read all the books about him, and watched the way he’s done it, the way he keeps it going. He’s truly extraordinary.

“It’s more of a problem than most people realize for a musician to make a living in music. You can use a show like Hair. The show covers up the music. If there’s music there, the people who want music like it, but meanwhile there’s something for them to watch. People don’t understand pure music. They can understand dance music, but that’s really a cop-out, if you go to a dancehall and just play dance music. When Ellington plays a dance, he always takes time out to present something artistic.

“Some nights that I’ve been to hear him, he wouldn’t play much, but there were always guys who sounded nice, although maybe nothing special actually happened. Other nights, I’ve seen him when he never left the piano, never even bothered to talk much. It was all happening at the piano. Those were the really good nights, but you can’t rely on them always. He has to have something else, a routine, that is part of the business of working every night. It probably isn’t necessary for him to work all the time, but I know he likes to, because it is his way of keeping in touch with music. That’s hard to do. I know, because for recording sessions I have to keep digging up things, just to keep going, to play, to make music.”

Despite their obvious differences, did he feel that both Hair and Two Gentlemen of Verona had the same basic jazz intent?

“Although it has that fine band, Two Gentlemen of Verona is not so much of a jazz show. It’s not after freedom but humor. John Guare, who did the lyrics, is a very funny and clever guy, so the music tried to be, too. And it’s very ethnic ... . Because it falls into divisions I wrote Puerto Rican, Afro-Cuban and West Indian music, as well as parodies of old-fashioned Broadway songs.”

The two New York successes were only a part of this prolific composer’s output. What happened when he went to London in 1969?

“I teamed up with an underground poet named Bill Dumeresque for a musical called, Who the Murderer Was. It was rather a weird situation—murder with songs. We had four singers, like a Greek chorus. Dumeresque does beautiful lyrics that are somewhat depressing, but to me they’re humorous, too. All the songs were written specially for the show, but it didn’t click.

“The following year, we tried another play with songs, Isabel’s a Jezebel. It was partly successful at the Mercury Theatre, but not when it moved to the West End. It was, very strong and far-out, almost like Becket, but without Becket’s appeal. It was just like a soap opera—about abortion and the relationship between a man and a woman—and the songs, about life and love, possibly seemed irrelevant. The critics hated it and were offended by our doing it. I think they were probably justified. Although it was interesting in a psychological way, it was not entertaining, and the theater critics will say you are not doing what you should. You are supposed to make people think, but it’s hard to know how far you can go in commercial theater. People read the newspapers to find out whether they should go to a play or not, and in this case, the critics honestly didn’t think they should.”

During 1971, MacDermot wrote Ghetto Suite, which consisted of songs and poems by Harlem and Bronx schoolchildren set to his music. He also wrote a mass.