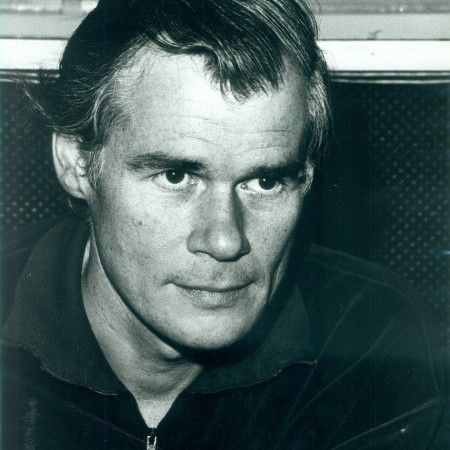

Galt MacDermot (1928–2018)

(Photo: Dagmar/DownBeat Archives)“It was no big theatrical event, just a setting of the Anglican service. I would like people to do it. In my daughter’s school, in fact, the kids all know and sing it. It’s like a hymn, one long hymn, and that was the idea of it. In addition, I’ve been writing a wind quartet for my wife, who used to play clarinet in an orchestra. It’s a nice thing for a composer to do, and it’s fun. I wrote a few such things when I was going to school, and I do the arrangements for the shows I write. But doing this is altogether different from writing for a 14-piece band where you have a rhythm section to carry it and you use the brass to fill. This is completely carried by itself. It’s fanciful composing, but it has a little of that African feeling. The rhythms are West Indian, and every time I play piano, it tends to have that West Indian lope. The heavily African beat is much more in West Indian music than it ever was in jazz. The guys in the quintet are classical, however, very Juilliard-type guys.”

Alongside all these activities, he has for a considerable time been making records as Fergus McRoy, a pseudonym for a Nova Scotian folksinger.

“I have a record company of my own, and I’ve made several albums. A guy in Canada has been trying to sell them, without much success, and arrangements are being made for their distribution here on the Kilmarnock label. The first batch will include Ghetto Suite, a couple of film soundtracks, the original cast recording of Isabel’s a Jezebel, two of McRoy’s sets, a rock album and so on. My name isn’t really known and I haven’t bothered about promotion. That way, I stay free of the business end of things. Because I write all the time, I’ve written hundreds of songs, and I like making records. Fergus McRoy, this character I’ve created, provides me with a way of using them. I suppose a few people might be interested, but the record business is very much tied up with promotion, and promotion is so boring, tiresome and demoralizing that you’d rather quit than put up with it all. Except that you don’t want to quit the business of music.”

“I think the record industry has had a serious effect on young people, in making them think there’s only one way to write. When I was growing up, I wanted to write symphonies and operas, and then I wanted to have a band like Duke Ellington’s. There were all kinds of things I wanted to do. I lived in a dream world, and because I didn’t know the realities of anything, there were all kinds of interesting possibilities. But nowadays, the only thing you can hear is a hit record, or Muzak, which you don’t really listen to. So, it’s hard to say how kids’ tastes are formed now. When I was young, one or two of us used to go to the store every day to find out about new records. Our son, who’s 14, listens to the radio for hours, and sometimes he tapes half a record he wants to hear again. But not jazz, nor the other kind of records I grew up with, the fantastic kind we used to call ‘race’ records. I don’t hear anything like them anymore, except really commercial versions. Where is the counterpart of Joe Turner, the young guy like him?

“As I said earlier, I don’t feel much is happening in pop music, but you tend to say this every six months, that there’s nothing happening, and the next thing you know something happens that you like. But everything gets exploited so heavily. I like country music, but I can hardly take the country records I hear now. The same with rhythm and blues. You don’t hear new ideas; people are afraid of ideas. They want to get that funky feeling—and I like that—but if there’s no idea you can’t go far.

“You can identify the source of nearly everything played by the young jazz guys coming up. They’re not original. An Erroll Garner can’t happen anywhere but here, although for some reason it doesn’t seem to have been happening recently. I think the reason may be economic, or the fact that the hit record is all anyone aims for. That used to not be so when I played in a dancehall, when we made the people dance. There was a whole different way of playing, when you worked on the rhythm, and over a period of time something would happen. Now, the kids don’t get work until they have a hit record, and then they don’t know what it is they’re trying for.

“As for jazz being an expression of some kind of political or ideological belief, I don’t think politics is worthy of a musician’s consideration at all. It’s like tax collecting. Of course, money is important to you, but it’s not interesting. Music is so much more important. I’m always astonished when I hear musicians talking about politics, just like they talk about their cars.”

MacDermot’s career obviously has been anything but boring. To attempt to predict its future course would be decidedly foolish, but all those who were delighted by the freshness of the approach to Two Gentleman of Verona will scarcely be surprised to know that more Shakespeare with his music is in the offing. After he finished Hair, he went back to producer Joseph Papp ready to write an opera. They had discussed this before, and Papp now suggested the relatively little known Troilus and Cressida.

“There’s terrific poetry in it, and little speeches, which make nice songs. When I had finished it, Papp didn’t know how to deal with it, either. I rather wanted to drop it. But there is some music I like in it, and I’m thinking of making a record of it. One of the problems was whether it should or should not be in suits of armor. I felt it ought to be in the clothes people wear now. The fact that Shakespeare’s not easy to understand was another difficulty, especially since all of it, in this case, would be sung. Tom O’Horgan wants to do a Broadway version of it, but I can’t imagine people going to a Broadway theater and understanding it. He believes, and I partly agree, that if you keep the eye delighted and the ear amused, it will be acceptable enough. It is, after all, a simple story about a guy and a girl falling love, but it’s not a mass thing in the same sense as Superstar.

MacDermot has also written a musical about outer space called Via Galactica, which Nat Shapiro wanted to produce.

“I’ve written another show with Gerry Ragni called Dude. It’s about American life, the same kind of thing as Hair. Ragni has the extraordinary view of things. He sees them differently. He is in his mid-30s, a very interesting guy who writes in a strange way. He has a jazz mentality, and, instead of lyrics, he lists ideas. They are not in song form and you have to do the best you can. That’s how Hair was done.”

Both shows are due on Broadway this season. DB