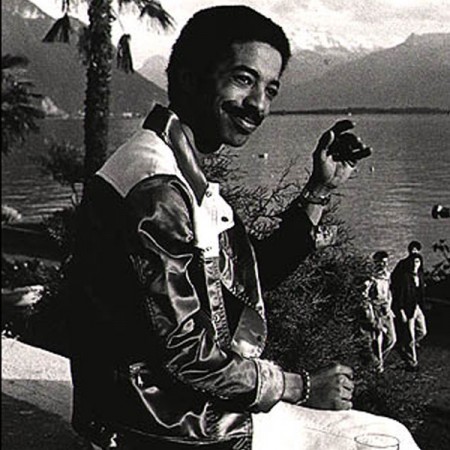

Tony Williams

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)Tony Williams erupted onto the jazz scene in 1963 as a 17-year-old prodigy with a full-blown, volcanic style of drumming that would blow hard-bop tastiness out the door. Williams’ arrival was hailed with a great deal of fanfare. The week he came with Miles Davis to San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop, the club temporarily relinquished its liquor license so the underage genius could play. (I remember, because it was the first time I was allowed in as well.)

Williams played the drums that week at a level of energy and activity—not to mention volume—that was not only exciting, but liberating. Whirling from crash to ride to slack hi-hat, now pummeling, now ticking, now coaxing, he machine-gunned the bass drum, pulled low-pitched “pows” from the toms and jagged bursts from the snare as if his legs and arms were connected to four separate torsos. His complex, distinct style, which owed a lot to the floating time of Roy Haynes and thrust of Elvin Jones (Sunny Murray’s unbridled freestyle was a simultaneous development rather than an influence), suggested that jazz drumming might exist as an adjunct to, as well as support for, the rest of the band.

Williams stayed with Davis five years. In 1968, like Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter before him, Williams left Miles, smelling rock ’n’ roll in the air. Joining forces with keyboard man Larry Young and British guitarist John McLaughlin (whom Tony discovered but Miles snatched into the recording studio first, for In A Silent Way), the drummer recorded a groundbreaking jazz-fusion trio album, Emergency, for Polydor (recently reissued as Once In A Lifetime, Verve), of psychedelic fervor and volume. For a while it looked as if Tony Williams was going to take the electric ’70s by storm, as he had the acoustic ’60s.

But it didn’t turn out that way. At Polydor he suffered poor management, poor promotion, and poor sales. Fans who had exhaled “far out” for Emergency dumped Turn It Over and Ego into the used record bins. The critics lambasted him, crying, “Sellout.” Williams, for all his bravado a vulnerable fellow, retreated, confused. From 1973–’75 and again from 1976–’79 he vanished as a leader. When he did come back, with Columbia, it was with the crisp, straightahead rock of Believe It, pumped full of hot air by a discoing promotional department. Jazz fans shook their heads, wondering what had happened to their young hero. After an exhibitionist tour de force, Joy of Flying, in 1979, on which he amassed everyone from Cecil Taylor to Tom Scott, Columbia dropped Williams in the middle of a seven-record contract. More than ever, he began to look like the Orson Welles of jazz, bursting into the world with creative energy only to make a long, agonizing finish. One critic, Valerie Wilmer, even went so far as to dismiss him as a showman.

But Wilmer, and others, weren’t really paying attention. While it was true that Tony Williams hadn’t come up with any project matching the creative vision of Emergency or the late ’60s Miles quintet (hard acts to follow), he had certainly held his ground, which is considerable. He is every bit as good a jazz drummer as he was 20 years ago, as his recent performance in Seattle with VSOP II attested. Besides, none of the other great jazz drummers—Max Roach, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones—has altered his style after its initial breakthrough. Williams’ work in rock has been a mighty influence, right down to the current work of Journey’s Steve Smith.

As for integrity, Williams has this to say to his critics: “People have this thing that if you like pop music, it’s because of the money. My career will tell you I’ve never done anything for the money. Writers and critics and people in the jazz world think you cannot possibly like the Police because of the music, which is absurd. I do the things I do because they excite me, and the rest is a load of rubbish.”

Williams continues to tour both in rock and jazz situations. In 1980 he played Europe with young Portland, Ore. fusion keyboardist Tom Grant and Missing Persons bassist Pat O’Hearn; in 1981 and ’83 he toured with VSOP. He plays on one track of Grant’s Columbia album You Hardly Know Me, and on several with Wynton Marsalis, who replaced Freddie Hubbard in VSOP.

In 1977 the drummer moved from New York to Marin County, north of San Francisco, where he lives now with his girlfriend. Three days a week he drives to UC-Berkeley, where he is studying classical composition with Robert Greenberg. When he is not composing fugues or studying counterpoint (“It’s a mountain of work,” says Williams), he is in the studio in San Francisco or busy catching up on some of the things he missed growing up a superstar: playing tennis, swimming, learning German, and driving his Ferrari. Williams says the move to California has revitalized his creative life and helped him to get past the tangled 1970s.

DownBeat: You completely changed jazz drumming in the 1960s. Were you consciously aware at any certain point that you were doing something new?

Tony Williams: Not really. I guess I was aware that I was playing differently, but it was more of a thing that I was aware of a need, like if you see a hole, you think you can fill it. There were certain things that guys were not playing that I said, “Why not? Why can’t you do this?”

DB: How important was Alan Dawson, your teacher in Boston, in your development of independence in all four limbs?

TW: What I basically got from Alan was clarity. He had a lot of independence, but so did other people. I get this question about independence a lot, even from drummers, but they can’t even be clear about their ideas. I mean you hear them play something, and you say, “What was it that he played?” Or if they hear themselves back on tape, they say they thought they played good but that it didn’t sound like that. So the idea is that when you play something for it to sound like what you intended, not to have a “maybe” kind of sound. So that’s what I got from Alan, the idea that you have to play clearly.