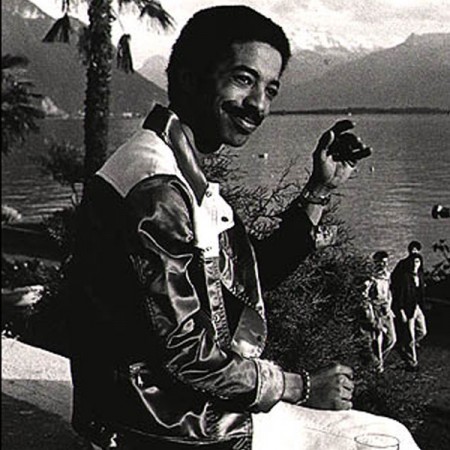

Tony Williams

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)DB: Were you thrilled to be part of the Miles band in the ’60s?

TW: Well, when you’re doing things it’s hard to say, “Oh gee, this is going to be real historical sometime.” I mean you don’t do that; you just go to the sessions, and 10 or 20 years later people are telling you that it was important. When you’re doing it, you can’t really feel that way.

DB: What is your relationship with Miles now?

TM: Very friendly. I saw him this summer. I haven’t heard the new albums, but when we played opposite him, I heard bits and pieces of the band, and Miles was sounding good. He’s been practicing. I liked Al Foster [Miles’ drummer] years ago, when I was with Miles.

DB: You’ve played with a lot of illustrious musicians. Being a drummer, you have to adapt to each one differently. Let’s talk about some of them, say, beginning with Sonny Rollins and McCoy Tyner.

TW: Sonny has a very loose attitude about things—the time, the whole situation. With McCoy I always felt like I was getting in his way, or that it never jelled. I felt inadequate. Actually, with both Sonny and McCoy, it’s like you’re playing this thing, and they’re going to be on top of it.

DB: How about John McLaughlin and Alan Holdsworth?

TW: Completely different. John is more rhythm oriented. He plays right with you, on the beat. He’ll play accents with you. Even while he’s soloing, he’ll drop back and play things that are in the rhythm. Alan is less help. With Alan it’s like he’s standing somewhere and he’s just playing, no matter what the rhythm is.

DB: Wynton Marsalis and Freddie Hubbard?

TW: Freddie plays the same kind of solo all the time. I get the feeling that if Freddie doesn’t get to a climax in his solos, and people really hear it, he gets disappointed. With Wynton it’s always different. I don’t know what he’s going to play. It’s always stimulating.

DB: I gather you think Wynton Marsalis’ manifesto about only playing jazz—and not funk or rock—is not that important?

TW: He thinks it’s an important attitude. That’s what counts.

DB: A lot of fans and critics still find a contradiction in your playing what they see as oversimplified rock as well as the kind of complex jazz you played with Miles and you play now with VSOP. What’s your reaction to that?

TW: Well, first of all, just because it’s jazz, doesn’t mean it’s going to be more complex. I’ve played with different people in jazz where it was just what you’d call very sweet music. No type of music, just because it’s a certain type of music, is all good. A lot of rock ’n’ roll is not happening. And a lot of so-called jazz and the people who play it are not happening. Complexity is not the attraction for me, anyway—it’s the feeling of the music, the feeling generated on the bandstand. So playing in a heavy rock situation can be as satisfying as anything else. If I’m playing just a backbeat with an electric bass and a guitar when it comes together, it’s really a great feeling.

DB: You were quoted in [an article in] Rolling Stone, praising the drummer in the Ramones. Were you serious?

TW: I don’t remember the occasion, but I do like that kind of drumming, like Keith Moon, any drumming where you have to hit the drum hard; that’s why I like rock ’n’ roll drumming.

DB: Sometimes so much of that music seems very insensitive.

TW: It depends on what you’re saying the Ramones are supposed to be sensitive to. Just because it’s jazz doesn’t mean it’s going to be sensitive. You’re trying to evoke a whole other type of feeling with the Ramones. When I drive through different cities and I look up in the Airport Hilton and I see the sign that says, “Tonight in the lounge, ‘live jazz’”—I mean, what the hell does that even mean? I’m not saying everybody’s like this, but I can see a tinge of people saying, “This is the only way it was in 1950, and we’re going to keep it that way, whether the music is vital or not, whether or not what we end up playing sounds filed with cobwebs.” When John Coltrane was alive, there were all kinds of people who put him down. But these same people will now raise his name as some sort of banner to wave in people’s faces to say, “How come you’re not like this?” These same people. That’s hypocrisy, and I find it very tedious.

DB: How important is technique?

TW: You’ve got to learn to play the instrument before you can have your own style. You have to practice. The rudiments are very important. Before I left home, I tried to play exactly like Max Roach, exactly like Art Blakey, exactly like Philly Joe Jones, and exactly like Roy Haynes. That’s the way to learn the instrument. A lot of people don’t do that. There are guys who have a drum set for two years and say they’ve got their own “style.”

DB: How can we prevent those kinds of guys from taking up more room than they deserve?

TW: [laughing] Well, we could pass a law.