Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

In Memoriam: Al Foster, 1943–2025

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

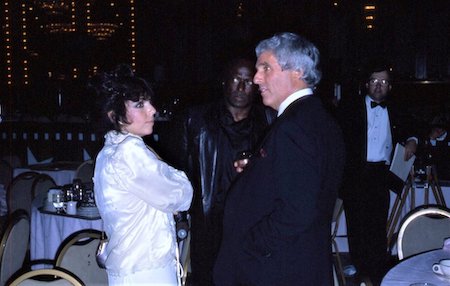

Burt Bacharach with Carol Bayer Sagar and Miles Davis in 1984.

(Photo: John McDonough)Burt Bacharach, who died in Los Angeles at age 94 on Feb. 8, was among the last of a small, oddly isolated island of popular songwriters in the mid-to-late 20th century. In the late 1950s they inherited the torch of the Great American Songbook legends, only to see it flicker and fade in the ’60s as young audiences decided that authenticity was a greater virtue than craft. Within a decade rhythm and blues, folk and rock erased the specialization that had separated singers from composers, hyphenating them into the more emotionally (and financially) integrated “singer-songwriter.” As autobiography replaced imagination, a new kind of artist arose: half a singer, half a songwriter.

As a full-time composer, Bacharach found himself a thirty-something throwback. Born in 1928, he had grown up in the ’30s and ’40s when the alliance between jazz and popular music was an intimate brotherhood. When he wrote his first hit in 1957 (“Magic Moments”), the link still seemed strong. Ella Fitzgerald’s songbooks were everywhere. Andre Previn and Shelly Mann were charting with My Fair Lady and L’il Abner music. And Miles Davis was recording “If I Were A Bell” and “Someday My Prince Will Come.”

Bacharach was not the only newcomer then. Johnny Mandel, Michel LeGrand and Stephen Sondheim emerged about the same time and faced a similar isolation. They had much in common, not only with each other, but more importantly, with the generation of composers they had hoped to succeed. All were born within six years of each other. Except for LeGrande, all were Jewish. None was a singer; all depended on the favor of others to “cover” their work to the public. All were professionals who could write to story specs. Their skills were negotiable in the theater, on screen and in the studio.

Most important, all came to the 1960s with a keen feel for jazz, but at a time when jazz and popular music were divorcing. Yet, each would write songs that would enter the modern jazz canon. Mandel’s “Shadow Of Your Smile” would log nearly 700 jazz recordings; “Emily,” 467, (including 39 by Bill Evans alone). LeGrande’s list is equally imposing: “What Are You Doing For The Rest Of Your Life,” “I Will Wait For You,” “The Summer Knows” and “Windmills Of Your Mind.” Sondheim’s music has always had a longer fuse. Yet “Send In The Clowns” has scored 232 jazz interpretations.

Outside of Bacharach, however, no modern popular composer would create more hits that would join the modern jazz repertoire. JazzStandard.com, which lists the 1,000 most performed songs in all jazz, includes at least four.

Despite the indifference of many jazz musicians toward the rock and pop scene after 1970, Bacharach’s clever rhythms and harmonies became his passport into the jazz world. He broke the protocols of structure, which made his music seem tricky to those thinking in four-bar terms. “Changing meters, surprising harmonic shifts and other interesting twists,” Ted Gioia wrote in The Jazz Standards, “are married to memorable melodies in a way that might seem perfectly suited to a jazz performance.” Bacharach’s popularity could not be held against him. Daniel Fagen once described his work as “Ravel-like harmonies married to street-corner soul.”

Though Gioia wondered why more Bacharach songs have not become jazz standards, musicians as diverse as Stan Getz, Roland Kirk, Scott Hamilton, Marian McPartland, Wynton Kelly, Dick Hyman, Chet Baker, Jackie McLean, Sonny Rollins and Bill Frisell would quickly discover him, along with singers such as Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Carman McRae.

Bandleaders Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Buddy Rich, Woody Herman and Count Basie commissioned Bacharach arrangements in their styles. Ellis Larkins, Grant Green and Nicki Parrott each devoted CDs to his work. In 2004 Blue Note issued Blue Note Plays Burt Bacharach, an anthology featuring Stanley Turrentine, the Jazz Crusaders, Ernie Watts and others. In 1996 even McCoy Tyner recorded a Bacharach songbook album on Impluse! with Christian McBride, Lewis Nash and John Clayton arranging and conducting. Bacharach himself had a recording career, though not an important one. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits has no listing for him. It’s one more thing he has in common with Gershwin, Kern, Berlin, Arlen and his other musical ancestors.

In the end, that’s why composers like Bacharach are the real immortals. The notes they leave on paper are not the music, only the treasure maps to where it’s buried. It is up to future generations of performers to find it, dig it up and turn it back into music, always contemporary. DB

Foster was truly a drummer to the stars, including Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson.

Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

“Branford’s playing has steadily improved,” says younger brother Wynton Marsalis. “He’s just gotten more and more serious.”

May 20, 2025 11:58 AM

Branford Marsalis was on the road again. Coffee cup in hand, the saxophonist — sporting a gray hoodie and a look of…

“What did I want more of when I was this age?” Sasha Berliner asks when she’s in her teaching mode.

May 13, 2025 12:39 PM

Part of the jazz vibraphone conversation since her late teens, Sasha Berliner has long come across as a fully formed…

Roscoe Mitchell will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Vision Festival.

May 27, 2025 6:21 PM

Arts for Art has announced the full lineup for the 2025 Vision Festival, which will run June 2–7 at Roulette…

Benny Benack III and his quartet took the Midwest Jazz Collective’s route for a test run this spring.

Jun 3, 2025 10:31 AM

The time and labor required to tour is, for many musicians, daunting at best and prohibitive at worst. It’s hardly…