Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Blindfold Test: Buster Williams

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

While recording There Is A Tide, Chris Potter was able to focus on thinking like a producer.

(Photo: Bill Douthart)What’s the most important thing that you learned from making Tide, and is it transferable to post-pandemic work for you?

In this case, I was really able to think as a producer and spend the time on it that you never have making a jazz recording. The longest record dates that I’ve ever had were maybe three days, and so basically you’re coming in and you’re playing the music with people that you’ve played the music with before, hopefully. One of my keys to trying to make a good record is to have a chance to play the music with a band first, so that you get to know what the tune is, and what it wants to be and how you approach it and work out some of those kinks before you get into the studio. But that’s a document of a performance, and this is clearly something else that I had to edit.

It gave me the opportunity to think about, “OK, it’s going to start with this one texture, and how long is it going to be on that texture? And then something else should happen that’s related”—all these things that are kind of more like making a good pop record come to the fore, along with the fact that I just don’t have the virtuosity on all these instruments. Like, I can’t just play a killing drum part that whips it up into a frenzy if I want.

I realized quickly that the thing that I could do that sounded the best was just make sure that it grooves all the time. Then if I wanted more activity in that way, I’d add percussion or something. Just like when you hear Sgt. Pepper: These choices about how things are done have an effect on the way that you listen to it. That’s a whole other skill set that I’ve always been interested in. Virtually all of my working life has been focused on being a saxophone player, playing with people and improvising with them. You don’t get to focus on those details quite so much.

The second Circuits Trio album, Sunrise Reprise, is going to be the fourth project you’ll have released through Edition. You also did the Crosscurrents Trio album with them. They’ve let you experiment. Obviously, you’re a big get for the label, but is that freedom why you partnered with them?

Yeah, that’s been the thing—just the artistic freedom and the kind of forward-thinking way that they’re approaching it. The thing that’s different about them, they started well after the whole recording-industry system had pretty much collapsed. Definitely when I moved to New York and all through the ’90s, it was just a much different landscape.

They’re operating from this premise—social media—of getting information out that doesn’t necessarily cost a lot of money, but is going to reach some folks. I feel like I have complete freedom to do what I want—and complete trust from them. As I was saying, I wasn’t even necessarily sure that I wanted to put [Tide] out or that it was at a level that I should put it out. But they were like, “Yeah, do it.”

What did Stapleton say that convinced you?

Well, I think that was the first time anyone had really heard it. I felt like I was in a room of mirrors and I lost perspective: Is this good? So, [his wanting to release the album] was a bit of a vote of confidence, like, “It actually sounds good; I think it would be something people would be interested in, especially as it documents this particular time.”

That’s what I was hoping for; that was its function for me. It’s therapy to deal with everything and that’s kind of how it functions, anyway, I think. Musicians, we’re making music for other people to hear, but we’re also making music for ourselves—something that we feel we need to do to express what we don’t know how to express any other way. And if an audience finds value in that, that’s an extremely gratifying thing. But I wasn’t really sure about it.

I haven’t listened to it now in a couple months, so it’ll be interesting to let it go. I was just completely immersed in it. It’ll be good to hear it someday from enough distance that I might be able to actually judge it.

Even with the freedom that Edition has offered you, big-band projects—especially after the pandemic—are going to be tough to record and tour.

Well, that’s always been an issue. The ECM record—The Underground Orchestra, the Imaginary Cities record—I would have loved to have done a lot more concerts with that band. I hope we can still do more someday. That’s like 11 people; it’s a lot and it’s hard to do. You can sometimes use [local musicians] from wherever you go for certain things, but it’s not the same as the actual people that you call to be on the recording. We’ll have to figure it out as we go along. All these kinds of things, the infrastructure of how that’s gonna work, it’s all a bit of a mystery.

Some of the larger ensemble things that I’ve been writing and that I’ve been thinking about doing could involve using an established group—using the radio bands that exist in Europe. That’s an amazing resource that’s still holding on.

Having revenue come in from your music, it’s a problem for all of us—even to just fund recordings. I think there are different ways to do it: There are grants; there are other ways. I mean, musicians have always found a way to make what they need to make. But the financial situation, it clearly has a lot of impact on the scene. What would Duke Ellington be doing, you know? Would he still be able to keep his big band together? He kept it together through thick and thin—the same folks. And he did it, from what I can tell, with a lot of little gigs. He’d drive through Iowa and do dances. It wasn’t all Carnegie Hall.

Would you ever want to do a project like Tide again?

I don’t know—we’ll have to see. I would prefer that the circumstances that led to it being made don’t occur again. That’s for sure.

I think some good things can come from [this moment], which is kind of the message of the [song titles’] poem. There’s all this intense stuff going on, but there’s the possibility of change that comes from when people are so uprooted from what’s comfortable for them—and when change is so obviously needed.

The whole thing, at the end of it for me, it’s sort of an optimistic take on it. And it kind of moves in that way. The name of the first tune, “I Had A Dream,” that’s pretty pessimistic. It’s almost saying, “There was this amazing thing—and maybe not.” Then it moves through to a more optimistic frame of mind. DB

This story originally was published in the January 2021 issue of DownBeat. Subscribe here.

“What I got from Percy was the dignity of playing the bass,” Buster Williams said of Percy Heath.

Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

Don and Maureen Sickler serve as the keepers of engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s flame at Van Gelder Studio, perhaps the most famous recording studio in jazz history.

Sep 3, 2025 12:02 PM

On the last Sunday of 2024, in the control room of Van Gelder Studio, Don and Maureen Sickler, co-owners since Rudy Van…

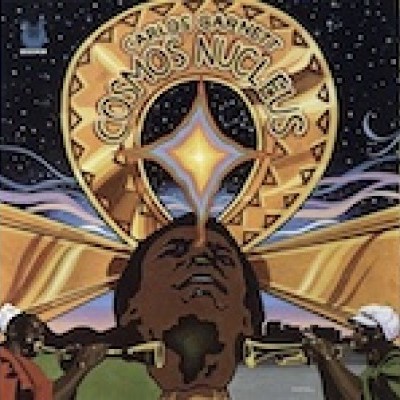

The Free Slave, Cosmos Nucleus and Sunset To Dawn: three classic Muse albums being reissued this fall by Timer Traveler Recordings.

Aug 26, 2025 1:32 PM

Record producer and “Jazz Detective” Zev Feldman has launched his next endeavor, the archival label Time Traveler…

This year’s Jazz em Agosto set by the Darius Jones Trio captured the titular alto saxophonist at his most ferocious.

Aug 26, 2025 1:31 PM

The organizers of Lisbon, Portugal’s Jazz em Agosto Festival assume its audience is thoughtful and independent. Over…

Trio aRT with its avalanche of instrumentation: from left, Pheeroan akLaff, Scott Robinson and Julian Thayer.

Sep 3, 2025 12:03 PM

Trio aRT, a working unit since 1988, shockingly released its very first studio recording this summer. Recorded in…