Mar 4, 2025 1:29 PM

Changing of the Guard at Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra

On October 23, Ted Nash – having toured the world playing alto, soprano and tenor saxophone, clarinet and bass…

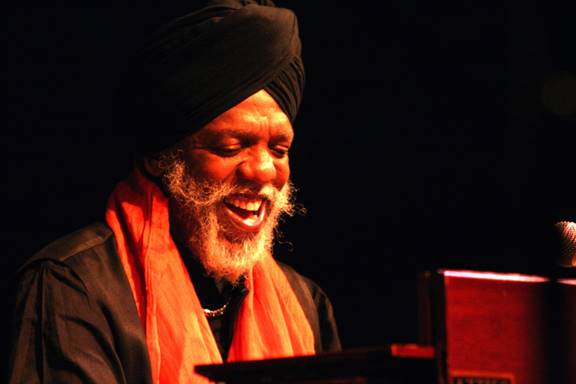

“When I go up on that stand, the only thing I’m thinking of is music.” —Dr. Lonnie Smith

(Photo: Courtesy Blue Note Records)Dr. Lonnie Smith, one of the greatest musicians to ever touch the Hammond B-3 organ, died Sept. 28 at home in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. He was 79 years old.

His death was confirmed by his manager Holly Case. The cause was pulmonary fibrosis.

“Doc was a musical genius who possessed a deep, funky groove and a wry, playful spirit,” said Don Was, president of Blue Note Records, the jazz label for which Smith recorded many of his masterworks. “His mastery of the drawbars was equaled only by the warmth in his heart. He was a beautiful guy and all of us at Blue Note Records loved him a lot.”

Smith made his name on Blue Note in the late 1960s and returned home to the label in 2016. He was born in Buffalo, New York, on July 3, 1942. His mother sparked a love of gospel, blues and jazz in Smith. As a teenager he was introduced to the Hammond organ and began immersing himself in the records of Wild Bill Davis, Bill Doggett and Jimmy Smith, as well as paying attention to the church organ.

Smith’s first gigs were at the Pine Grill, a Buffalo club where he came to the attention of Lou Donaldson, Jack McDuff and George Benson, eventually joining Benson’s quartet and moving to New York City.

After appearing on Benson’s albums It’s Uptown and The George Benson Cookbook, Smith released his debut, Finger Lickin’ Good, for Columbia. He then joined Donaldson’s band and made his first Blue Note appearance on the saxophonist’s hit 1967 album Alligator Boogaloo. Two more Donaldson dates followed (Mr. Shing-A-Ling and Midnight Creeper) before Smith was offered his own Blue Note deal. He made his label debut in 1968 with Think!, produced by Blue Note co-founder Francis Wolff.

Smith went on to record another four Blue Note albums over the next two years: Turning Point, Move Your Hand, Drives and Live At Club Mozambique, all regarded as soul-jazz classics.

After his first run of Blue Note albums, Smith recorded for many labels, including Groove Merchant, Palmetto and his own label, Pilgrimage. His wide-ranging musical tastes found him covering everyone from John Coltrane to Jimi Hendrix to Beck. Many awards have followed since 1969, when a DownBeat poll named Smith Organist of the Year, including honors from the Jazz Journalists Association and Buffalo Music Hall of Fame. Smith was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2017.

“I always sang,” Smith said in a March 2008 cover article for DownBeat. “My family sang spiritual music at home, and before I went into the service, I’d sung in churches. Then we had a four-part harmony singing group called the Supremes, which we changed to the Teen Kings. A disk jockey named Lucky Pierre managed us, and we made a record. But I always loved to play musical instruments. The first time I touched a piano, I’d just graduated to third grade, and I went to visit my aunt. I got up to the piano and figured out how to play ‘Crying In The Chapel.’

“I never had a piano, but I learned a little about the keyboard by fooling around,” he continued. “I knew some boogie-woogie, and natural things like that. My mother and I used to scat to instrumental songs, and I played trumpet and tuba in high school, but I’d play piano in the school auditorium, or at someone’s house, like Grover Washington, who I grew up with. I’d play songs by Fats Domino or Little Richard — what they played had a lot of feeling, and wasn’t so complex that you couldn’t understand what they were doing. A friend played me Jimmy Smith’s Midnight Special record, and I heard Wild Bill Davis, Bill Doggett and Milt Buckner, too. My brothers played bass, guitar and drums, and on the jobs I’d sing a few songs, then sit on the side while they kept playing. I wanted to get up there so bad! It looked like they were having too much fun. I borrowed a Wurlitzer. I’d play a couple of songs, and I’d be happy.”

Earlier this year, Smith released his final album, Breathe, a dynamic eight-song set, six tracks of which were recorded during Smith’s 75th birthday celebration at the Jazz Standard in New York in 2017 with his steady trio of guitarist Jonathan Kreisberg and drummer Johnathan Blake, as well as an expanded septet featuring John Ellis on tenor saxophone, Jason Marshall on baritone saxophone, Sean Jones on trumpet and Robin Eubanks on trombone, plus guest vocalist Alicia Olatuja.

“I have so much passion,” Smith told DownBeat writer Ted Panken in 2008. “I had an algebra teacher who got real involved, and would shout, ‘Yeah, that’s it!’ and start writing out the answer. That’s how I feel when I’m playing, so enthused and so happy. I’m pleasing myself first, and you’re next. The Hammond is such a warm sound — the feel of the earth, the sun, the moon, the water — and it matches so well with the Leslie. The horn that goes around inside the Leslie moves slow and fast — when you close the switch on it, it’s like a nasal sound; when you open the switch, it’s like the earth opened. Later, I’m out of breath, I don’t want to talk, I don’t want to do nothin’, I just want to go home and relax. It’s so pleasant, unless somebody pisses you off on the stage. Sure, sometimes people you play with don’t match too good. But 99% of the time I’m having a ball.”

Part of the joy that Smith brought was from his soulful music, but another part was from his electrifying persona. Often asked about how he became a “doctor” and why he wore his trademark turban, Smith offered a beautiful response.

“I know you were trying to get to it,” he said, mildly amused. “You got it. Sun Ra had a miner’s cap, and Sonny Rollins had the mohawk hairdo. But I’m a doctor of music. I’ve been playing long enough to operate on it, and I do have a degree, and I will operate on you. I’m a neurosurgeon. If you need something done to you, I can do it. But when I go up on that stand, the only thing I’m thinking of is music. I’m thinking to touch you with that music. I don’t think about the turban, I don’t think about the doctor — I just think about how I’m going to touch you.” DB

Editor’s Note: This obituary was assembled by DownBeat staff based on information submitted by Blue Note Records.

As Ted Nash, left, departs the alto saxophone chair for LCJO, Alexa Tarantino steps in as the band’s first female full-time member.

Mar 4, 2025 1:29 PM

On October 23, Ted Nash – having toured the world playing alto, soprano and tenor saxophone, clarinet and bass…

“This is one of the great gifts that Coltrane gave us — he gave us a key to the cosmos in this recording,” says John McLaughlin.

Mar 18, 2025 3:00 PM

In his original liner notes to A Love Supreme, John Coltrane wrote: “Yes, it is true — ‘seek and ye shall…

The Blue Note Jazz Festival New York kicks off May 27 with a James Moody 100th Birthday Celebration at Sony Hall.

Apr 8, 2025 1:23 PM

Blue Note Entertainment Group has unveiled the lineup for the 14th annual Blue Note Jazz Festival New York, featuring…

“I’m certainly influenced by Geri Allen,” said Iverson, during a live Blindfold Test at the 31st Umbria Jazz Winter festival.

Apr 15, 2025 11:44 AM

Between last Christmas and New Year’s Eve, Ethan Iverson performed as part of the 31st Umbria Jazz Winter festival in…

“At the end of the day, once you’ve run out of differences, we’re left with similarities,” Collier says. “Cultural differences are mitigated through 12 notes.”

Apr 15, 2025 11:55 AM

DownBeat has a long association with the Midwest Clinic International Band and Orchestra Conference, the premiere…