Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

In Memoriam: Al Foster, 1943–2025

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

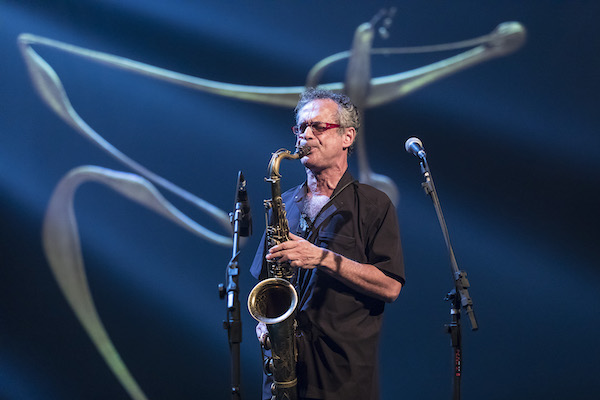

During the pandemic, prolific saxophonist Ivo Perelman moved from Brooklyn to Brazil.

(Photo: Edson Kumasaka)In 2020, soon after the pandemic reached Brooklyn, Ivo Perelman’s base of operation for decades, the tenor saxophonist decided to relocate to Fortaleza, a city in the northeast corner of his native Brazil. Perelman appreciates the daily routines he’s established since then: a jaunt to the beach, diving in the Atlantic Ocean and hours of studying bel canto opera. Since his move, these disciplines have provided Perelman with “the perfect combination for life,” he said during a December Zoom call.

Arguably, Perelman stands as one of the most prolific free improvisers around: In the past three decades, he’s recorded about 100 albums, the bulk of them for British label Leo Records. His eponymous 1989 debut, Ivo—with its coterie of no- table guests like drummer Peter Erskine, percussionist Airto Moreira, pianist Eliane Elias and singer Flora Purim—established his bona fides as an avant-garde talent; he would go on to work with eminent creative musicians like drummer Andrew Cyrille, bassist Reggie Workman, and pianists Paul Bley and Joanne Brackeen.

Perelman recently added three new albums to his massive oeuvre, each project wholly improvised and unique in character. In crafting each, the only concept Perelman brought into the studio with him was “to open my ears and heart to my fellow musicians, because that’s how the dialogue takes place.”

In November, Perelman released Shamanism (Mahakala 009; 50:04 ***1/2), a trio album with two of his long-standing collaborators, pianist Matthew Shipp and guitarist Joe Morris. Shifting between lyricism and bold expressivity, the album’s 10 tracks show off the bandleader’s ease in the challenging altissimo register on the saxophone. While Shipp and Morris probe fleeting harmonic ideas on tunes like “Spir- itual Energies” and “Religious Ecstasy,” Perelman catapults from the lower sonority of his instrument into the breathy, high-pitched wails and rasps that characterize his instrumental style.

Shipp and Morris join the reedist in this esoteric musicality as equals; each player contributing in fair measure to the heft of impromptu compositions. Perelman ac- knowledges that the trio’s easy rapport makes for an advanced collective expression: “It’s a three-way synergy of sorcerers,” he said.

For his January release, The Garden Of Jewels (Tao Forms 004; 50:57 ****), Perelman chose a different tack for the trio format. With Shipp again on piano, Perelman invited drummer Whit Dickey to contribute a percussive layer to the intuitive communication. But he “didn’t want this album to become a ‘Perelman-Shipp duo plus drums,’” he noted.

Excitement arises out of the trio’s adherence to the inner logic of Perelman’s ideas—the synced rhythmic patterns on “Tourmaline,” for instance, or the textural shading beneath the continuous horn line on “Turquoise.” The radiant sound of the ensemble led Perelman, who also is a painter and jewelry maker, to the project’s apt title: “[All of the tunes] are like a precious stones, exquisitely polished—like a garden of jewels,” he said.

Perelman never had played in a duo with a trumpeter until Polarity (Burning Ambulance 71; 39:15 ***), his February release alongside Nate Wooley. On this album—the most idiosyncratic of the three— the pair uses just breath and imagination to craft articulate expressions of spontaneous communication. One hears how Perelman’s study of bel canto has paid off: His control of each declarative phrase is su- perb, as he integrates aesthetic elements culled from the classical repertoire.

As the pandemic stretches on, Perelman has begun to think about returning to Brooklyn. He’s eager to get back into the studio and apply recent breakthroughs in his daily practice to improvising. In fact, he’s hoping to rerecord some or all of his existing discography with the same personnel, simply to see how his playing has changed. It’s a wild idea, he admits, but likely to happen. “Somehow, I always end up doing things that sound impossible,” he figured. DB

Foster was truly a drummer to the stars, including Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson.

Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

“Branford’s playing has steadily improved,” says younger brother Wynton Marsalis. “He’s just gotten more and more serious.”

May 20, 2025 11:58 AM

Branford Marsalis was on the road again. Coffee cup in hand, the saxophonist — sporting a gray hoodie and a look of…

“What did I want more of when I was this age?” Sasha Berliner asks when she’s in her teaching mode.

May 13, 2025 12:39 PM

Part of the jazz vibraphone conversation since her late teens, Sasha Berliner has long come across as a fully formed…

Roscoe Mitchell will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Vision Festival.

May 27, 2025 6:21 PM

Arts for Art has announced the full lineup for the 2025 Vision Festival, which will run June 2–7 at Roulette…

Benny Benack III and his quartet took the Midwest Jazz Collective’s route for a test run this spring.

Jun 3, 2025 10:31 AM

The time and labor required to tour is, for many musicians, daunting at best and prohibitive at worst. It’s hardly…