Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

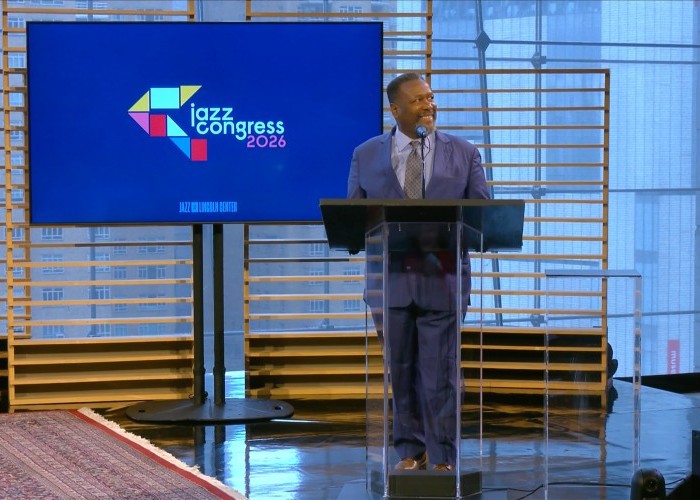

Actor and jazz advocate Wendell Pierce delivers the keynote address at this year’s Jazz Congress on Jan. 7 in New York. “This music was born of the contradiction of a people creating beauty out of pain,” he said.

(Photo: Jazz at Lincoln Center)“The Jazz Olympics,” one attendee called it. Indeed, the first full week of January 2026 is the most event-packed in the jazz community’s calendar. The academic side of the equation was concentrated in New Orleans for the Jazz Education Network’s annual conference; the performing and industry side went to New York for the Jazz Congress, with many of them sticking around for the weekend’s Winter Jazzfest marathons in Manhattan and Brooklyn. This writer went the latter route.

I arrived at Jazz at Lincoln Center, the site of the Jazz Congress, on the first day — Wednesday, Jan. 7 — just in time to find that the lunchtime sessions were at capacity: disappointing, since I’d wanted to participate in a Yusef Lateef listening session led by guitarist Charlie Apicella; there are much worse consolation prizes, though, then hearing pianist Miki Yamanaka playing solo in the atrium, which is what I did instead.

The afternoon, however, brought a plenary session that began with this year’s Bruce Lundvall Visionary Award. It went to journalist and Jazz Congress co-producer Lee Mergner — who wryly noted that he had co-created the award. “When I sent the order back in October,” he related, “He called me up and said, ‘So is this dummy copy? Because it has your name on it.’ … Charlie was happy to make his $337, but even he questioned the choice.”

After Mergner came the conference’s keynote address, delivered by actor and jazz advocate Wendell Pierce. It was a rousing, inspiring speech about the purpose and continuing need for art in society. “This music was born of the contradiction of a people creating beauty out of pain,” he said. “Jazz has always been a critique of American mythology. … Art is not propaganda, but it is also never neutral. It doesn’t lie, it doesn’t simplify, it doesn’t flatter power.”

Drummer, bandleader and educator Terri Lyne Carrington led a panel discussion on the evolving state of jazz in 2026, with insightful contributions from journalist and podcaster Angelika Beener, trumpeter Keyon Harrold and saxophonists Caroline Davis and Logan Richardson (the lattermost, in particular, shot out of a cannon). Closing out the evening, moderator Willard Jenkins spoke to the recipients of first Jazz Legacies Fellowship, a new award from the partnership of the Mellon Foundation and the Jazz Foundation of America in support of artists aged 62 and over. The inaugural class included Bertha Hope, Carmen Lundy, Amina Claudine Myers, Herlin Riley and Reggie Workman (all of whom performed the next night, Jan. 8, in a concert that was part of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Unity Jazz Festival).

The second day of the Jazz Congress was as fascinating as the first, kicking off with another solo piano performance: this time by Tyler Bullock, who provided the soundtrack to the morning registration and coffee scramble. Then, Carrington, bassist Linda May Han Oh, singer-percussionist Branda Navarrete and tap dancer Michela Marino Lerman discussed “Women in Rhythm” in Dizzy’s Club. The assembled panel demonstrated the importance of rhythm by teaching the audience to sing, clap and dance a polyrhythmic composition by Geri Allen. Seton Hawkins, JALC’s director of education, and vocalist Nicole Odreman-Valenciano led a late-morning listening session of the music of trombonist and arranger Melba Liston, with insights on both her life and her music from the mid-1940s through the ’90s in the complex’s Louis Armstrong Classroom.

After lunch, in the Appel Room, came one of the congress’s most interesting and timely discussions. NPR’s Katie Simon led a discussion with musician/activists Joey La Neve DeFrancesco and Luke Stewart as well as author Liz Pelly about the changes that streaming has wrought on the music world, and on jazz in particular. The discussion debunked a number of myths and provided little-understood perspectives into how the industry operates with the streaming platforms: especially how the major recording companies consistently put their thumbs on the scales of the so-called “neutral” algorithms, to their own benefit — and usually to the detriment of jazz. (Pelly’s book, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, is an invaluable resource on the subject.)

There was much more to be heard and learned at the Jazz Congress, even as the above were going on. (Down the hall at the same time streaming conversation, for example, was a panel discussion on the future of jazz on public radio, with another on mentoring across the hall from that.) Soon enough, though, the conference was over and festivals beckoned.

JALC follows the Jazz Congress with its own in-house festival, Unity Jazz Festival, which this year was highlighted by the Jazz Legacies Fellowship Concert and by the Trinidadian soca group Kes (with special appearance by trumpeter Etienne Charles). This year, though, this writer was drawn instead to Winter Jazzfest, the popular event now in its 22nd edition. WJF’s most popular feature is its two-night marathon of jazz concerts, the first (Jan. 9) in Manhattan and the second (Jan. 10) in Brooklyn.

Once confined to Greenwich Village, the Manhattan marathon now spreads across multiple neighborhoods. I chose to begin at the small SoHo club Close Up, where bassist John Hebert awaited with his quartet The Youngbloods. After their wonderful, energetic set featuring Korean gayageum player DoYeon Kim came a stop at the East Village’s Drom, where Iraqi-American trumpeter-composer Amir ElSaffar led a fiery performance by his own quartet; another at Nublu, just a few blocks away, for the electro-jazz duo of Sam Gendel and Nate Mercereau; and, well, a lot of standing in line in the Village (increasingly an occupational hazard as the festival grows in popularity).

It paid off, though, in the Paris Jazz Club’s sponsored lineup at The Bitter End. Two French bands, the organ-piano-drums trio The Getdown and the electronic-acoustic-weirdness fusion trumpeter Daoud and his quartet, provided rewarding and exciting music with a heaping side of populism, engaging the crowd in great fun and lively banter. (Daoud’s popular refrain, coming two nights after Renee Good’s death in Minneapolis, was “Fuck ICE.”)

The Brooklyn marathon remains contained in one neighborhood, Williamsburg, but within that boundary might have offered the more adventurous and compelling musical lineup. Flutist Nicole Mitchell got things rolling at National Sawdust with a new quartet, Black Earth SWAY, the combined cutting-edge jazz with funk and R&B, one of the night’s most groove-centered and soulful sets.

Two doors down, at Williamsburg Music Hall, guitarist Tsziji Munoz and keyboardist Paul Shaffer co-led Quantum Blues, a band whose output was closer to Jimi Hendrix than, say, Wes Montgomery (but was great fun to listen to and had its own language and vocabulary). The acoustic guitar duo of Yasmin Williams and William Tyler was scheduled to follow; Tyler, however, was sick, leaving Williams to her own devices. Her fingerpicking melded folk, blues, classical and jazz guitar into something that was uniquely her own, if in a short 30-minute set.

The strings dominating at Williamsburg Music Hall became even more so at the small Broadway club Baby’s All Right. Bassist Luke Stewart led the way with his Silt Trio, a freeform ensemble also featuring tenor saxophonist Brian Settles and drummer Chad Taylor, with poet and spoken-word artist Janice Lowe joining for a closing piece (and Stewart also reciting the words of poet No Land). Following that came the Tomeka Reid Quartet, with cellist Reid joined by guitarist Mary Halvorson, bassist Jason Roebke and drummer Tomas Fujiwara, in what Reid announced as the album release show for their album dance! skip! hop! They performed all of the new album’s five tracks magnificently.

The Reid set did run late, however, causing this writer to have to literally run in order to catch trumpeter Adam O’Farrill, who at Loove Annex was leading his new quartet Elephant. It was a fearsome performance, with, if anything, pianist Yvonne Rogers, bassist Walter Stinson and (especially) drummer Russell Holzman topping O’Farrill — though not by much — for sheer ferocity. It was worth the run, with the closing “The Return,” a tribute to the late David Lynch, as a mesmerizing highlight.

Was it a lot to take in? Clearly. Yet it’s hard to imagine more visceral and dispositive proof that jazz is thriving in 2026. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…