Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

In Memoriam: Al Foster, 1943–2025

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

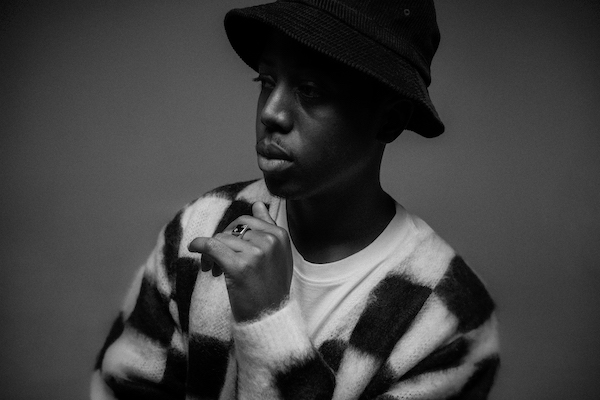

Moses Boyd, who’s set to release his debut Dark Matter, says he likes “being a bit uncomfortable.”

(Photo: Dan Medhurst)Drummer Moses Boyd has served as London’s rhythmic instigator since introducing himself with the Footsteps Of Our Fathers EP in 2015.

With several accolades, including the Steve Reid Innovation Award, as well as acclaim for his work with Binker Golding in Binker & Moses, the drummer is set to issue his debut album, following a string of EPs and singles. From his home in London, Moses discusses his perspective on recording, collaborating and “the secret” to Dark Matter, which is due out Feb. 14 on the drummer’s Exodus Recordings.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Where did the concept for the title Dark Matter come from?

I’m a huge fan of space; I just love the concept of dark matter in astronomy terms, you know? Then on a more macro-level—with what’s been going on throughout the last two years while making the record—we’ve had The Windrush [Scandal] and Brexit. I was making music that was reacting to what was going on. It’s not overly political, it’s just human.

Explain the journey you’ve been on since the release of the Displaced Diaspora EP in 2018?

Displaced Diaspora came out in 2018, but it was recorded in 2015; I started working on Dark Matter just before Displaced Diaspora was released. I guess it’s interesting that everyone is saying [Dark Matter] is the debut album—which to me it is. But Displaced Diaspora came out and I didn’t really know how to describe it or talk about it, because for me it was like, “This moment happened and I captured it.” I’ve learned a lot about playing music and recording music; I’ve done a lot of production and writing and working with other people. It’s more of a culmination of my skills as a drummer and as a writer. It’s a very produced record, and I guess maybe it’s like a summary of what I’ve been learning and what I’ve been picking up between 2015 and now.

I don’t really see myself as just a drummer, just a jazz musician or just a writer anymore—I just make sounds, man. I’ve gotten a lot better at making sounds over the years.

How did you come to work with the musicians on Dark Matter? Did you approach people in order to create a certain sound or did you choose them with an open mind? It’s definitely the former. If I’ve made a beat, I can hear if it’s for me. If it is, I can decide if it’s completely just me and if there’s no features on it, but sometimes—in certain songs—I can hear that it wants someone extra. I think it was definitely that when I wrote “Dancing In The Dark.” I was like, “There’s only one voice that I want on it, and that’s Stephen Obongjayar.”

Sometimes, the songs just fit a certain person. “2 Far Gone” was definitely an homage to Herbie Hancock, which I did with Joe [Armon-Jones]; I wanted to hear him on the piano. I got to play with Joe many years ago on corporate gigs and stuff—a lot of people don’t get to hear that side of Joe, on an acoustic piano. We recorded in his living room on his upright, in one take. He had no idea [that I was using it for “2 Far Gone,”] until I played it back to him. He was like, “Oh my gosh, I don’t remember doing that.”

Can you recall any poignant moments from collaborations that you’ve had during the past few years that have helped you realize your own individual direction?

For sure. Doing Zara McFarlane’s Arise album was one of those; the whole process was quite interesting because Zara’s very direct. She knows what she likes. She had the concept of the record long before we started working on it, this kind of reggae-jazz hybrid. I made the music first and then she wrote [lyrics] to it.

From a creative point of view—especially when you’re working with singers—it’s really tricky, because I have no idea where the lyrics are going. Zara’s very much an artist; she has to live life to write them. The lyrics fit perfectly, and that changed the way I thought about how I write music, because prior to that, I was doing a lot of composing at the piano, a very sort of jazz perspective, which is cool. I consider myself an open person, but I just wasn’t aware of how many other options I had. It really allowed me to have fun as a producer and a drummer.

I’m attracted by things that I don’t know—or a process I’m not used to. It might sound strange but I like being a bit uncomfortable.

Speaking of which, do I hear Gary Crosby talking about energy on “What Now” and “Hard Food Interlude?”

Yes, Gary’s one of my dear friends and mentors. He’s always been a spring of wisdom for me. He’s got a very good perspective on stuff, so we just sat down and had a conversation. I didn’t necessarily know what I was looking for, but I knew he would say something of importance.

Let’s talk about the influences behind Dark Matter: It’s an intersection of jazz, afrobeat, grime and club culture. When did you become aware of those influences showing themselves?

It was very organic really. I’m not a signed artist. I don’t have anyone breathing down my neck saying, “When’s the next thing coming,” you know? I was pretty much halfway done [with Dark Matter] by the time Displaced Diaspora had come out. I experimented with putting electronic and acoustic things together, and that’s kind of the secret to the whole album. I was walking around with a hard drive for a long time, because I would go to people’s houses and be like, “Could you just record me this piano idea?” So over time, this whole album formed really naturally. Maybe that’s the result of the people I was working with and their own influences. Naturally, the music I was listening to at the time influenced me, too.

I was interested in how sounds make you feel. I wasn’t concerned with structures or chords. DB

Foster was truly a drummer to the stars, including Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson.

Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

“Branford’s playing has steadily improved,” says younger brother Wynton Marsalis. “He’s just gotten more and more serious.”

May 20, 2025 11:58 AM

Branford Marsalis was on the road again. Coffee cup in hand, the saxophonist — sporting a gray hoodie and a look of…

“What did I want more of when I was this age?” Sasha Berliner asks when she’s in her teaching mode.

May 13, 2025 12:39 PM

Part of the jazz vibraphone conversation since her late teens, Sasha Berliner has long come across as a fully formed…

Roscoe Mitchell will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Vision Festival.

May 27, 2025 6:21 PM

Arts for Art has announced the full lineup for the 2025 Vision Festival, which will run June 2–7 at Roulette…

Benny Benack III and his quartet took the Midwest Jazz Collective’s route for a test run this spring.

Jun 3, 2025 10:31 AM

The time and labor required to tour is, for many musicians, daunting at best and prohibitive at worst. It’s hardly…