Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

Muhal Richard Abrams (1930–2017)

(Photo: Michael Jackson)Asked about influences, Abrams said, “I find different ways of doing things by coming out of the total music picture.” His short list includes pianists James P. Johnson, Art Tatum, Earl Hines, Bud Powell, Hank Jones and Herbie Nichols, who “individualized the performance of mainstream music and their own original music”; Vladimir Horowitz and Chopin’s piano music; the scores of Hale Smith, William Grant Still, Rachmaninoff, Beethoven and Scriabin, as well as Duke Ellington, Gerald Wilson and Thad Jones. “So many great masters,” he said. “Some influenced me less with their music than the consistency and level of truth from practice that’s in their stuff.”

The influence of Abrams’ musical production radiates consequentially outside the AACM circle. Vijay Iyer recalled drawing inspiration from Abrams’ small group albums Colors In 33rd and 1-OQA+19 (both on Black Saint).

“Muhal was pushing the envelope in every direction, and that openness inspired me,” Iyer said. “The approach was in keeping with the language of jazz, but also didn’t limit itself in any way; the sense was that any available method of putting sound together should be at your disposal in any context.”

“I think my generation clearly heard the effect that the AACM and Muhal had on Steve Coleman and Greg Osby, who played with Muhal,” Jason Moran added. “We took some of that energy into the late ’90s, and it continues on to today. He defines that free thinking that most jazz musicians say they want to have.”

Both Lewis and Moran cite the methodologies of Joseph Schillinger—whose textbooks Abrams pored over during set breaks on late-’50s gigs in Chicago—as a key component of Abrams’ pedagogy. “It helped me break the mold of sitting at a piano and thinking what sounds pleasing to my ear, and instead be able to compose away from the instrument—to almost create a different version of yourself,” Moran said.

“Schillinger analyzed music as raw material, and learning the possibilities gives you an analytical basis to create anything you want,” Abrams said. “It’s basic and brilliant. But I don’t want to be accused of being driven by what I learned from Schillinger. I am the sum product of the study of a lot of things.”

This was manifest at the January 2010 NEA Jazz Masters concert at Rose Theater, when the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, encountering an Abrams opus for the first time, offered a well-wrought performance of “2000 Plus The Twelfth Step,” originally composed for the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band.

As the 15-minute work unfolded, one thought less of the predispositional differences between Abrams and Wynton Marsalis, and instead pondered Abrams’ 1977 remark: “A lot of people will pick up on the [AACM’s] example and do very well with it … who those people will be a couple of years from now, who knows?”

Indeed, it seems eminently reasonable to discern affinities both in the scope of their compositional interests and their mutual insistence on constructing an institutional superstructure strong enough to withstand the vagaries of the music marketplace.

When asked to comment, Abrams said, “It’s two different setups, but both very valid. There’s no real underwriting for the music of the streets. Never was. It’s very important for an entity to maintain a structure in which work can be expressed to the public, whatever approach or style they use.”

For the AACM, he continued, “The organizational structure was necessary to the extent that we were involved in the business of music. But it did not supersede or overshadow the central idea, which was to allow the individuals within the group a forum to express their own particular worlds. There was no hierarchy. Everyone was equal. As time has shown, every individual from that first wave of people came out as a distinct personality in their own right.

“If you want a house with 10,000 rooms, you don’t complain because nobody has a house with 10,000 rooms to give you. You build it yourself, and do it with proper respect for the rest of humanity. You’re busy working at what you say you are about—doing it for yourself. When you take a different way, people often get the impression that you are against something else. That certainly wasn’t true in our case—we never threw anything away.

“I just go as far as the eye can see in all directions. There’s no finish to this stuff.” —Ted Panken

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

D’Angelo achieved commercial and critical success experimenting with a fusion of jazz, funk, soul, R&B and hip-hop.

Oct 14, 2025 1:47 PM

D’Angelo, a Grammy-winning R&B and neo-soul singer, guitarist and pianist who exerted a profound influence on 21st…

To see the complete list of nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards, go to grammy.com.

Nov 11, 2025 12:35 PM

The nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards are in, with plenty to smile about for the worlds of jazz, blues and beyond.…

Drummond was cherished by generations of mainstream jazz listeners and bandleaders for his authoritative tonal presence, a defining quality of his style most apparent when he played his instrument unamplified.

Nov 4, 2025 11:39 AM

Ray Drummond, a first-call bassist who appeared on hundreds of albums as a sideman for some of the top names in jazz…

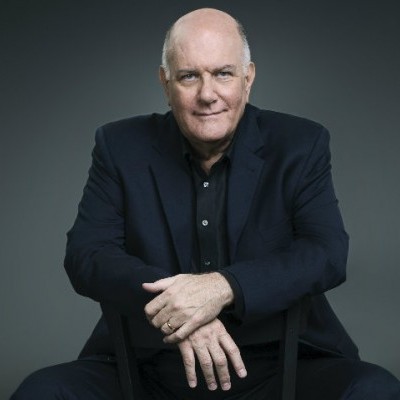

Jim McNeely’s singular body of work had a profound and lasting influence on many of today’s top jazz composers in the U.S. and in Europe.

Oct 7, 2025 3:40 PM

Pianist Jim McNeely, one of the most distinguished large ensemble jazz composers of his generation, died Sept. 26 at…