Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

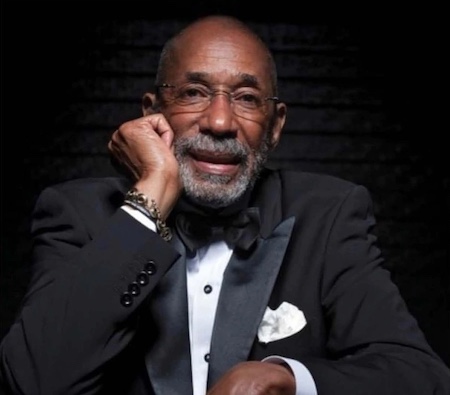

Bassist-composer Ron Carter turns 85 on May 4.

(Photo: Atilla Kleb)On May 10, the iconic bassist-composer Ron Carter will be fêted in an 85th birthday celebration at Carnegie Hall. With NBC Nightly News anchor Lester Holt (himself a bass player) acting as emcee and bass greats Buster Williams and Stanley Clarke providing personal testimonies, the evening will include performances by Carter-led groups in three combinations: his longstanding Golden Striker Trio with pianist Donald Vega and guitarist Russell Malone, his Foresight Quartet with tenor saxophonist Jimmy Greene, pianist Renee Rosnes and drummer Payton Crossley, and the Ron Carter Octet featuring the leader on piccolo bass alongside cellists Maxine Neuman, Zöe Hassman, Sibylle Johner and Dorothy Lawson and a rhythm section of pianist Vega, bassist Leon Baelson and drummer Crossley.

“The gig is on May 10th,” the revered octogenarian said about his Carnegie Hall gala, “and my birthday is May 4th. So I’ll have to make a note when I do my little talk to the audience and say, ‘You guys are six days late, but thank you, anyway.’”

The most recorded bassist in jazz history, with more than 2,250 recordings to his credit, Carter has collaborated with an array of artists ranging from Paul Simon, Billy Joel, Aretha Franklin, Roberta Flack, Diana Ross, Bette Midler, Phoebe Snow, The Rascals, Gil Scott-Heron (“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”) and Santana on the pop side to Bill Evans, Chet Baker, Stan Getz, Kenny Dorham, Lee Morgan, Coleman Hawkins, Cannonball Adderley, Kenny Burrell, Milt Jackson, Eddie Harris, Charles Lloyd, Sonny Rollins and countless others on the jazz side.

Few other musicians have amassed such a disparate discography. A prime example: He played cello on Eric Dolphy’s 1961 album Out There and bass on the 1991 hip-hop landmark Low End Theory by A Tribe Called Quest. His impressive list of credits from early in his career includes Randy Weston’s Uhuru Africa in 1960, Gil Evans’ Out Of The Cool, Wes Montgomery’s So Much Guitar and Bobby Timmons’ In Person (live at the Village Vanguard), all released in 1961. A string of ’60s Blue Note recordings — Tony Williams’ Life Time, Herbie Hancock’s Empyrean Isles, Maiden Voyage and Speak Like A Child, Wayne Shorter’s The Soothsayer and Speak No Evil, Joe Henderson’s Mode For Joe and The Kicker and McCoy Tyner’s The Real McCoy — brought him further esteem. Add to that ‘70s classics like Freddie Hubbard’s Red Clay, Tyner’s Extensions, Jim Hall’s Concierto, Antônio Carlos Jobim’s Stone Flower, Woody Shaw’s Blackstone Legacy, Stanley Turrentine’s Sugar and George Benson’s Beyond The Blue Horizon.

Perhaps most famous are his recordings with Miles Davis’ celebrated quintet of the mid-’60s. On the bandstand with Davis, alongside Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Tony Williams, Carter exuded a resolute presence and a sartorial splendor that has come to define his calm, elegant demeanor for more than six decades as a working pro. And while the six studio recordings that they made over the span of four years — 1965’s E.S.P. (which featured three Carter compositions), 1967’s Miles Smiles and Sorcerer and 1968’s Nefertiti, Miles In The Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro — are part of jazz legend, the gestalt group took things to a whole other level in concert.

“That was a laboratory band,” Carter said in a phone interview in advance of his Carnegie celebration. “We were always experimenting from night to night.”

That process of collectively stretching the boundaries by dispensing with standard 32-measure AABA forms common in Tin Pan Alley songs (a foundation of Davis’ first great quintet from the mid-’50s) and by dealing with more ambiguous melodic and harmonic elements propelled jazz out of the bebop era and into the future. And the music seemed to transport the audience, in turn, to a new place. With its more subjective treatment of standards, where meters shifted, chord changes became ambiguous and formal structure was deconstructed, Davis’ second great quintet was by far the most sophisticated, forward-thinking and risk-taking group of its time, with one foot firmly planted in the tradition and the other foot striding into The New Thing.

In concert, Davis’ band lived for those combustible moments of spontaneous creation. If you listen to recorded documents at the time like Live At The Plugged Nickel from 1965 or Live In Europe 1967: The Bootleg Series Vol. 1, it’s almost as if they eye-rolled their way through the changes, paying only half-hearted attention to the form in a rush to get to those moments of pure improv, where this band lived. Williams’ dynamic drumming was the polyrhythmic catalyst for this freer new direction. And while Carter’s bass was often cited as the anchor, his presence in the band was anything but sedentary. Indeed, his bass lines were alive from bar to bar, highly interactive with the other members of the quintet, often changing the course of things for the whole band, depending on whether he might break into a solid walk in any tempo, double a melodic line or provide spontaneous counterpoint, the latter a testament to his intensely focused listening and his classical training. As he put it, “I’m going to make sure the bass part sounds interesting every night.”

During pandemic times, Carter played on four recordings released in 2021: Gerry Gibbs’ Songs From My Father, Skyline with Gonzalo Rubalcaba and Jack DeJohnette, Jon Batiste’s Live At Electric Lady and Nicholas Payton’s Smoke Sessions. The revered Grammy-winner, 1998 NEA Jazz Master and 2012 inductee into DownBeat’s Hall of Fame also kept himself busy during the pandemic by completing two instructional books: Playing Behind The Changes and Chartography, both published in 2021 (roncarterbooks.com).

DownBeat spoke to Carter by phone prior to his 85th birthday celebration at Carnegie Hall.

Your first instrument was cello, which you studied from age 10 to 17. Why did you switch to upright bass?

Because I thought I wasn’t getting the chances that a talented African-American cello player should be getting. So I switched to bass because there was no bass player in the orchestra at Cass Technical High in Detroit.

And yet, you came back to the cello, documenting your concept for four cellos on 1978’s Songs For You.

Yes, that was a great time. I just wanted a new sound, not necessarily just to be different from everybody else’s, but something that I really wanted to hear. And that sound was four cellos playing with a nice jazz quartet background. And I’ve decided that I’m going to write more in that vein because I have a group now that’s understanding my intent. They want to see how far they can take this music with me. And they make themselves available when we all have time. So it’s a great composer setting for me and I’m looking forward to playing together again at the Carnegie Hall celebration.

After getting your bachelor’s degree from Eastman, you moved from Rochester to New York City in August of 1959. That was a very potent time for jazz. Kind Of Blue had just come out and later that year Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come and Charles Mingus’ Ah Um were released.

And Trane’s record [Giant Steps] also came out about that time. Yeah, it was an exciting time to be in New York. I had a scholarship to the Manhattan School of Music but I really went to New York to work. I had been in the house band at a club in Rochester that backed major jazz artists and I was told by several people who came through there — Sonny Stitt, among others — that New York always wants a good bass player. And they thought I could fit the bill so they encouraged me to come to New York when I graduated. So I came to New York looking for work, primarily, and my first gig there was with Chico Hamilton. I took over the bass spot for Bull Ruther [former Brubeck bassist, from 1951 to 1952, Wyatt “Bull” Ruther]. We went out on the 1959 Jazz for Moderns tour. It was a bus tour with other bands [Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, Dave Brubeck Quartet, Maynard Ferguson Orchestra and Chris Connor]. The band was Eric Dolphy on alto sax, bass clarinet and flute, Dennis Budimir on guitar, Nate Gershman on cello Chico on drums and myself on bass. We stayed together for about six months before the group eventually disbanded when Eric moved back to California. Eric was a special guy. I watched him develop what his point of view was with his constant practice routines he had every day, on the bus, in his hotel room, in his apartment. He’d practice four, five hours every day. I’d practice maybe a couple hours a day, but mostly I was practicing on the gigs.

Did you record with that band?

There’s some recording somewhere. They’re finding more and more stuff in the can. I’ve seen some bootleg stuff advertised, but I haven’t heard it. So I’m not sure what that is. Speaking of which, I just got an email yesterday that they found four recordings of Miles in Tokyo with the Sam Rivers band. So there are four new LPs that they just released only in Japan. I’m trying to track those down to see what’s on them. The only one legitimate record is Miles In Tokyo, which Columbia released in 2005. But evidently there are four others that they recorded along the way that have Sam Rivers. I’m trying to get a hold of those. I knew Sam from Boston and I heard him play in New York at his loft, Studio Rivbea. And I made some records with him, ultimately [1965’s Fuchsia Swing Song and 1967’s Contours, both on Blue Note]. I thought he was a wonderful player.

Tell me about Charlie Persip and the Jazz Statesmen.

That was my first band, other than the group with that Chico Hamilton band that went out on the road in 1959. The Jazz Statesmen was definitely the first band that I recorded with. It was Charlie Persip on drums, Roland Alexander on saxophone, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet and Ronnie Matthews on piano. Teddy Charles, the vibes player, was the producer for that record we made on the Bethlehem label.

You introduced a new sound with the piccolo bass on 1973’s Blues Farm and then showcased that instrument on your 1977 Fantasy album Piccolo.

Yeah, that’s a wonderful record. In terms of arrangements and concept, that band [Kenny Barron on piano, Buster Williams on bass, Ben Riley on drums] was really ahead of its time, not just because there were two bass players but because the arrangements were much more specific. It’s not a jam session kind of thing; it was a very organized band. There weren’t many bands at the time who were really groups like we were. Everyone was jamming with bop and free-jazz, but that group stood out because of the personalities in the band made it sound like one guy playing.

Talk about your involvement with the Fender electric bass.

At the time I came to New York, the electric bass was just getting its voice and the producers of commercials didn’t know which one they preferred — this new sound, the electric bass, or the old standby, the upright bass. So all the upright players went out and bought an electric bass. Richard Davis, George Duvivier, Milt Hinton … all those guys went out and bought one, including me. For a while, we were running around New York in cabs going from session to session with an upright on one arm and dragging an electric bass along.

And you incorporated the electric bass on your 1969 album Uptown Conversation.

Yeah, that was a really wonderful band: Sam Brown on guitar, Herbie Hancock on piano and electric piano, Hubert Laws on flute, Grady Tate and Billy Cobham alternating on drums. They just loved to play good music, and my job was to provide them something that they could really play, and we had a great time doing it.

Is the electric bass anything that you’ve been involved in recent years?

No. I gave it to my son, Ron Jr., long ago. I realized that to be competitive, I couldn’t do both, so I just invested all my time on upright. And I’m still looking for the right notes on upright.

Your very first album as a leader, Where?, was released in 1961. What do you remember about that session?

I was pleased that George Duvivier said that he’d make the record with me. He had a bar he opened in 1961 on St. Nicholas Avenue and 146th Street called The Bass Fiddle, and I would go by there after my gigs at night and talk with George. He had a great jukebox in there at the time. And he would ask me how I did this or that on the bass and what’s my aim in playing music. And when I called him to be the second bass player on this record date, he was just thrilled as if it was his first record date. Charlie Persip played on that along with Mal Waldron, who I began to understand what a wonderful composer he was. He wrote some nice songs and I had fun playing with him on my date. Eric Dolphy was also there. It was great to have those guys, all encouraging me for this project.

How did you come to join Miles Davis’ band two years later?

He came by when I was working with Art Farmer, Jim Hall and Walter Perkins at the Half Note, which was down on Spring and Hudson. After the set was over he called me over and said that he was putting together a new band because Paul [Chambers] and Jimmy [Cobb] and Wynton [Kelly] were going to join Wes Montgomery’s band. He had a tour coming up in a week and wondered if I would join the band. And I told him no, that I had a gig with Art Farmer, but if he would ask Art to let me be free of my responsibilities, I would do the gig. So Miles talked to Art and Art agreed to let me go. I left the next week with Miles on a six weeks tour to the West Coast.

There’s only one solo bass album in your entire discography, 1989’s All Alone.

Yeah, I wasn’t really interested in that part of the bass library. I thought it was necessary to make a statement that it’s possible to do it, but I had other eggs to cook. I just wanted to be a better composer, a better arranger. At the time, I didn’t have Finale or any other music software program for notation. I did it all by hand with a hell of a copyist. So I was learning what I wanted to do, literally from the ground up. But the bass on that record All Alone sounded really great that day. I just never got back to doing solo bass again, except on my live performances.

Speaking of becoming a better composer, there’s one tune of the 100 or so that you’ve written that I find just completely haunting. It’s “Mood,” the very sparse, chamber-like piece that has an evocative, almost Erik Satie feel. You recorded that piece on your 1969 album Uptown Conversation and more recently did a beautiful rendition with the WDR Orchestra on 2015’s My Personal Songbook.

And don’t forget Miles recorded it on E.S.P. I had a nice melody and what made it work, I think, was Tony Williams playing just some real sparse stuff for the whole track. That set the tone for the harmony and the pretty sparse melody that I came up with one day as I was fooling around, trying to see what I could hear that day. It’s a nice piece, it worked out really well, and I’m happy to add that to my small catalog of things that I wrote.

What others compositions do you regard highly?

“A Little Waltz” is one. That was on Uptown Conversation and some others I’ve done. It’s been recorded by a lot of people. We used to play it in the V.S.O.P. band. My current quartet [Rosnes, Greene, Crossley] likes that piece because it has some nice harmonies. I also wrote a piece called “Friends” for a record I did with the four cellos and Hubert Laws [1993’s Friends on Blue Note]. It’s a nice little melody. My current favorite piece is my bass lines to the Brandenburg Concerto No. 3.

Right, you did a Bach album.

Yeah, I did three. One was me playing the cello suites, only the dance movements (1987’s Japan-only release Ron Carter Plays Bach on the Philips label). Another was arrangements that I wrote for eight basses where I play all the parts (1992’s Ron Carter Meets Bach on Blue Note). It’s a pretty complicated project that [Hitoshi] Namekata, who headed up Something Else, Blue Note’s Japan division, put together. He encouraged me to write what I wanted to write, and he didn’t question my choices. I’ve never done that music live, not with eight basses. I’ve got four cellos in my back pocket. I’m good with that. [Carter also recorded 1996’s Brandenburg Concerto on Blue Note.]

A record you did that came out just before the pandemic was your collaboration with poet Danny Simmons on The Brown Beatnik Tomes: Live In Brick House. How did that come about?

When I first arrived in town, folk singing was really big in New York. And [bassist] Bill Lee [Spike Lee’s father] was the guy all the folk singers had to have in their accompanying band. [Indeed, Lee played on records by Odetta, the Chad Mitchell Trio, Tom Rush, Tom Paxton, Judy Collins, Ian & Sylvia, Peter, Paul & Mary and others]. Well, Bill could only do so many gigs at one time, and somehow he latched on to me as being his sub. So I did do some sub things for him. I played with Leon Bibb, Josh White, Theodore Bikel, Martha Schlamme. And I did some playing behind poets. So that was not a new one for me. And when Danny asked me would I do this for him, I was a little concerned. I asked him to send me to the poems so I could find out where it was going. Was it just a bunch of words, or did he have a point of view? And once he sent me a couple of poems I said, “I think I can help you make this work.” And we had a great time.

You mentioned earlier that you are still looking for the right notes on the upright. How would you assess your own playing today? Are you pushing yourself to improve on the instrument?

Every night. And I think the more I get a chance to play in different environments, I find out what the possibilities are for what the bass can do and I try them out to find somewhere else to go.

What specifically are you going for?

Note choices, presence, line development, consistency — that I’m going to bring it every night, a presence in the band. I’m trying to make all those things happen as part of getting a nice pair of shoes. Because when they feel good, man, everybody wants to step on them, you know? DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…