Mar 18, 2025 3:00 PM

A Love Supreme at 60: Thoughts on Coltrane’s Masterwork

In his original liner notes to A Love Supreme, John Coltrane wrote: “Yes, it is true — ‘seek and ye shall…

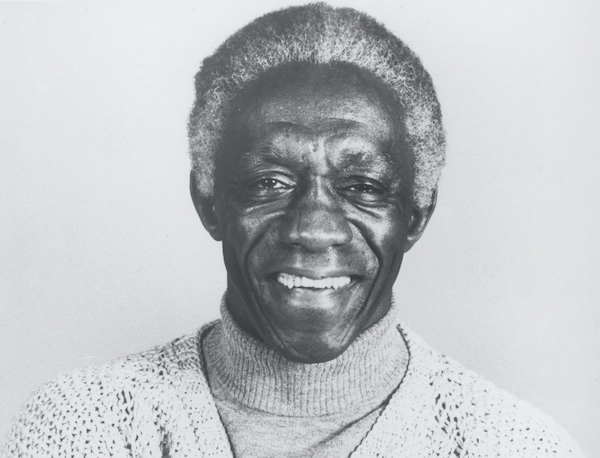

Art Blakey (1919–1990)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)Circa 2019, Blakey’s collective personnel constitute a who’s who of mainstream jazz expression. The list includes trumpeters Charles Tolliver, Woody Shaw, Eddie Henderson, Wynton Marsalis and Wallace Roney; saxophonists Jackie McLean, Gary Bartz, Carlos Garnett, David Schnitter, Donald Harrison, Kenny Garrett and Javon Jackson; trombonists Steve Turre, Slide Hampton and Steve Davis; pianists Walter Davis Jr., John Hicks, Keith Jarrett, McCoy Tyner, James Williams, Mulgrew Miller and Benny Green; and bassists Reggie Workman, Buster Williams, Charles Fambrough and Peter Washington.

On one recording, Blakey remarked, “I’m going to stay with the youngsters—it keeps the mind active.” Pragmatic motivations, not least of them financial, fueled his career-long predisposition to work with young musicians, but he also responded to emotional imperatives. In a 1987 interview, he said that he’d raised 14 children, some biological, some adopted. “I was an orphan,” Blakey said. “I like a family—it gives me something to live for. I learn from the kids. When the young guys come in the band, I learn from them.”

To be specific: Blakey’s father abandoned his mother during pregnancy. She gave birth to Blakey on Oct. 11, 1919, in Pittsburgh. She died when he was 6 months old. Blakey was raised by his mother’s cousin, a Seventh Day Adventist. Her home had a piano, which he learned to play. At 13, he learned of the adoption and responded by leaving home.

After a few months working in a steel mill, he parlayed his piano skills and can-do attitude into a gig at a local club. A few years later, the owner ordered Blakey to switch to drums after Pittsburgher Erroll Garner sat in on a tune. For the next several years, Blakey learned on the job, which spanned after-hours sets and breakfast jams, applying advice from local drum men (among them Kenny Clarke) to the nuances of directing a show from the drum chair.

Conflicting chronologies trace Blakey’s path from local hero to international avatar, but a likely scenario is as follows: During the latter 1930s, Blakey met drum master Chick Webb, who took him under his wing, and demonstrated proper execution of the force-of-nature press roll that would be a signature component of his flow.

In 1942, Pittsburgh native Mary Lou Williams—who’d returned home after a decade-plus with Andy Kirk’s Twelve Clouds of Joy—was impressed by Blakey’s skills and took him to New York’s Kelly’s Stables with a sextet. Subsequently, he led a group at Boston’s Tic Toc Club and toured with Fletcher Henderson.

In 1944, Dizzy Gillespie recruited Blakey to play drums with Billy Eckstine’s bebop big band, whose soloists included Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Fats Navarro, Dexter Gordon and Gene Ammons. “I was doing funny stuff on drums, trying to play shuffle rhythms,” Blakey said in Gillespie’s 1979 memoir, To Be, or Not ... To Bop. “He stopped me ... and said, ‘We want you to play your drums the way you play them.’”

Blakey’s page-turning conception rendered the rhythmic innovations of bebop with the dynamic control and showmanship of Webb and Sid Catlett, his lodestars. In 1947, the drummer performed on Thelonious Monk’s first Blue Note recordings, as well as important bebop dates by Navarro, Gordon and James Moody, and played in an octet iteration of the Jazz Messengers.

Blakey (aka Abdullah Ibn Buhaina) spent much of 1948 and early 1949 in Africa, absorbing drum language and Islamic philosophy. He then re-established himself in New York.

By 1950, he was a frequent presence at Birdland, as captured on several dynamic airchecks. As the decade progressed, he documented several collaborative drum summits with Afro-Caribbean masters, and fueled landmark releases by, among others, Monk, Mobley, Dorham, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Herbie Nichols, Horace Silver, Lou Donaldson and Clifford Brown.

In 1954, Blakey joined forces with the latter three players on the spectacular location date Night At Birdland. In the aftermath, Blakey and Silver consolidated with a more curated unit whose three bellwether albums set a template for the emerging approach dubbed hard-bop, where practitioners rendered bebop vocabulary with a hard-blowing, blues-tinged, churchy feel. When they parted ways in 1956, Blakey appropriated the Jazz Messengers title.

For the next two years, Blakey led several energetic but unfocused units. In 1958, he formed another benchmark band with Golson, who recruited fellow Philadelphians Morgan, Timmons and Merritt. That configuration made an LP titled Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers, which later would be known simply as Moanin’, after Timmons’ now-iconic opening tune. On the album, Golson tailored his compositions “Blues March” and “Along Came Betty” in ways that expanded Blakey’s timbral palette across the entire drum kit, establishing the orchestrational attitude that would inform the Jazz Messengers aesthetic until the end.

In fall 1959, Shorter assumed the tenor saxophone and music director chairs. He remained until summer 1964 (when he joined Miles Davis); during his tenure, Blakey refined and expanded the format. Paired with Morgan on the front line, Shorter contributed a string of now-classic tunes (among them “Lester Left Town,” “This Is For Albert,” “Ping Pong”) that captured Blakey’s elemental funkiness while postulating allusive, captivating, highbrow harmonic content. When Blakey shifted to a three-horn configuration in 1961, Shorter took full advantage of the new possibilities, while bandmates Hubbard, Fuller and Cedar Walton added to the mix, contributing pieces (“Down Under,” “The Core,” “A La Mode,” “Mosaic”) that remain highlights of the canon.

“Art was dogmatic in how he interpreted arrangements and wanted to present his band,” Workman said. The 2020 NEA Jazz Master joined the Messengers in 1962, after a year with John Coltrane. “He wanted the band to be uniform—well-dressed, well-presented, each set tight—like he’d been used to in his earlier days. We were trying to get Buhaina to move with the times, so we gave him arrangements that forced him to perform something different. When he did, it was something special vis-à-vis what happened before.”

As Workman added, Blakey, who lived as hard as he played, “had his habits over the years,” and could behave unreliably and obstreperously when in their thrall. “He was an institution,” Workman said. “He’d been through every band, every situation, the ups and downs, yin and yang. A lot of us went through it with him. He kept that institution together, and created a structure that enabled many of the young players who came along to find themselves in the music business.”

After the sextet disbanded, Blakey led short-lived units during the ensuing decade, none of sufficient duration to develop a distinctive identity until a 1975–’77 edition with Ponomarev and Schnitter, which played new Walter Davis Jr. compositions like “Uranus,” “Backgammon” and “Jodi.” In 1977, Blakey recruited Watson and James Williams, and encouraged them to write. Bill Pierce soon joined the mix.

They were still Messengers in 1980, as was Fambrough, when 18-year-old Wynton Marsalis replaced Ponomarev on the front line. With a book that mixed old standbys with new tunes featuring ’70s harmonies and beat structures (e.g., Watson’s “In Case You Missed It,” Williams’ “Soulful Mr. Timmons”), the Jazz Messengers were again synchronous with the zeitgeist—an aspirational landing spot for the best and brightest players.

“The challenge was to tailor what we were listening to into something that this man who had a proven formula would play,” Watson said. “It was open; Art depended on his composers. I’d sneak some Trane changes into my tunes, because Art wasn’t going to play a Coltrane tune.”

“It’s interesting to see the creative tension engendered by younger musicians trying to bring innovations into this packaged format,” Lynch said. “You can hear Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Olu Dara, Eddie Henderson, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Wallace Roney ... all of them playing ‘Moanin’.’”

One draw for the “youngsters,” Pierce observed, is that “something in Art’s music made you think, ‘Maybe I can do that,’ whereas Miles and Coltrane were a little further away. I won’t say it wasn’t intellectual, but not so much that you had to be a deep thinker to enjoy it.”

Blakey’s “young lions” frequently depict him doling out tough love as a quasi-father figure. Although Blakey’s comportment during his golden years was not exactly equivalent to the persona of, say, Fred Rogers, he had, Workman observed, “matured as a person.”

“I’d heard stories about how intense Art could be, but he wasn’t like that with us,” Pierce said. “He was a great manipulator. He was gifted at seeing what people needed to feel, so that he could get the most out of them. But I think he genuinely thought, ‘These are young, dumb assholes; I’d better help them out.’ The earlier guys were more or less his peers, or at least they tried to behave that way. We didn’t see ourselves as Art’s peers. We wanted to be in the company of the great man and learn as much as we could.”

“Art taught in the Socratic manner,” Branford Marsalis said. “He’d force you to think, and through thinking, you arrive at the answer.”

“He mirrored your personality back at you,” Harrison said. “If you were selfish, Art might show you that you’re selfish. He’d paid attention to all the people he’d been around. He told me: ‘When you get your band, make sure you realize every person is different, and don’t lose them. Figure them out, and nurture them until they get where they’re going.’ He told me things about the alto saxophone that nobody else ever told me—how to play with a trumpeter, how to play dynamics, how to use your throat. You’d have thought he was a saxophone teacher.”

Donald Brown recalled a rehearsal when Blakey deployed his piano background: “Art asked if I could voice the chord to give it more weight. I wasn’t sure what he was talking about, so he came over and demonstrated. For him to do that was a lesson you can’t put a price on.”

Still, Blakey mentored most effectively from the drum chair, backing up words with deeds. “He’d talk you through your solo, saying things like ‘play the blues’ or ‘double up,’ giving guidance on how to make your moves,” Harrison said.

“Playing with him and having him interpret my music was simultaneously experiencing something you’ve listened to and idolized, while participating in real time,” Lynch remarked. “Then you have a challenge of playing and listening. He’s like: ‘You can take it up to here, but if you can’t take it further, I will run over you and flatten you like a pancake—but go for it if you dare.’ When you got to that level, then the real stuff came out, all the extra-special goodies.”

Among the many Blakeyisms that alumni frequently cite is this gem: “This isn’t the post office.” Indeed, to be a Jazz Messenger was not a lifetime gig. Although it wasn’t always a smooth process, Blakey also taught by letting go.

“This is not a job,” he told an interviewer in 1973. “It’s not a right—it’s a privilege from the Almighty to be able to play music. We’re only here for a minute, small cogs in a big wheel. You’re no big deal; so you get up and do your very best. You play to the people—not down to the people.” DB

“This is one of the great gifts that Coltrane gave us — he gave us a key to the cosmos in this recording,” says John McLaughlin.

Mar 18, 2025 3:00 PM

In his original liner notes to A Love Supreme, John Coltrane wrote: “Yes, it is true — ‘seek and ye shall…

The Blue Note Jazz Festival New York kicks off May 27 with a James Moody 100th Birthday Celebration at Sony Hall.

Apr 8, 2025 1:23 PM

Blue Note Entertainment Group has unveiled the lineup for the 14th annual Blue Note Jazz Festival New York, featuring…

“I’m certainly influenced by Geri Allen,” said Iverson, during a live Blindfold Test at the 31st Umbria Jazz Winter festival.

Apr 15, 2025 11:44 AM

Between last Christmas and New Year’s Eve, Ethan Iverson performed as part of the 31st Umbria Jazz Winter festival in…

“At the end of the day, once you’ve run out of differences, we’re left with similarities,” Collier says. “Cultural differences are mitigated through 12 notes.”

Apr 15, 2025 11:55 AM

DownBeat has a long association with the Midwest Clinic International Band and Orchestra Conference, the premiere…

“It kind of slows down, but it’s still kind of productive in a way, because you have something that you can be inspired by,” Andy Bey said on a 2019 episode of NPR Jazz Night in America, when he was 80. “The music is always inspiring.”

Apr 29, 2025 11:53 AM

Singer Andy Bey, who illuminated the jazz scene for five decades with a four-octave range that encompassed a bellowing…