Nov 5, 2024 1:00 AM

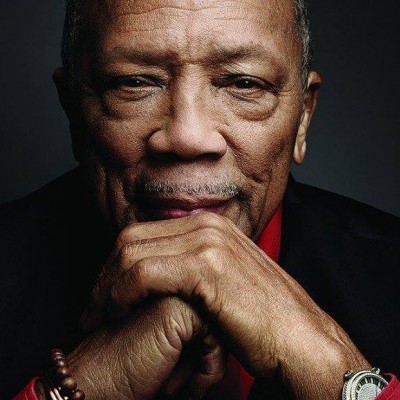

In Memoriam: Quincy Jones, 1933-2024

Quincy Delight Jones Jr., musician, bandleader, composer and producer, died in his home in Bel Air, California, on…

Carla Bley, the 2021 critics’ choice for the DownBeat Hall of Fame

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)

Given the tenor of the times, Carla Bley’s extraordinary career shouldn’t have happened. What were the chances in the 1950s that a teenaged girl from Oakland, California, would land smack in the middle of New York’s vibrant jazz scene, much less emerge as one of its most lasting compositional voices? Bley, who turned 85 this year, enters the DownBeat Hall of Fame after more than six decades of writing, recording and performing. In hindsight, the serendipity of Bley’s career is the stuff of movie plots: Freakishly talented composer-cum-cigarette-girl meets a rising-star pianist at a Manhattan nightclub frequented by Hollywood glitterati. Together, they absorb the new music in the air and claim a foremost spot in its vanguard.

In Bley’s story, the club was Birdland and the pianist was Paul Bley, who, by the time they married in 1957, had already proven his jazz mettle as a sideman for Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Chet Baker. He was becoming a leader in his own right, and his 1958 album Solemn Meditation would give the budding composer her first recorded track: the precocious “O Plus One.” By the early 1960s, she would be writing most of the material on her then-husband’s albums.

Paul Bley wasn’t the only prominent musician who championed Carla’s early work. George Russell, a leading light in the codification of jazz harmony, included her “Bent Eagle” on his 1960 album Stratusphunk; his imprimatur in particular granted the 24-year-old Bley legitimacy as a composer. Within the span of a decade, the number of influential bandleaders recording her work had multiplied. Jimmy Giuffre, Art Farmer, Steve Lacy, Steve Kuhn and Attila Zoller all made use of her talents.

Ever since her auspicious emergence on the New York scene, Bley’s distinction as a modern composer with a voice all her own has continued unabated.

“I’ve been moved to try new things in music by the ever-changing world around me. I’m strongly impacted by what I hear,” Bley explained via email from her home in Willow, New York. “And I almost always write for specific musicians. I’ve moved through many communities of players, and I’ve tried to provide each one with the perfect setting for his or her voice. This has led to some drastic shifts in idiom, but I think the sound of my own voice, like the color of my eyes or the way I walk, has endured through all the twists and turns.”

From an objective standpoint, charting the twists and turns of Bley’s musical evolution is tough, mostly because of the sheer volume of her creative output. She’s recorded more than 50 albums as a composer, arranger, player or leader. She’s performed in countless concerts with ensembles of differing configurations. And she’s collaborated with scores of music legends across genre and era. But her singular aesthetic — with its contrasting musical forms, dramatic tonalities and quirky humor — stands as the organizing principle for these many divergent elements.

If Bley’s work reveals a certain appreciation for classical idioms, it’s doubtless the result of years of hands-on training in childhood (her father was a church organist). This musical foundation proved sturdy enough for Bley to appreciate the complex vernacular she heard in the jazz clubs once she moved to New York; she was drawn especially to the meticulously crafted works of Count Basie and Thelonious Monk.

Duly entrenched with the avant-gardists during her initial years as a composer, however, Bley was busy turning out free, open compositions, written for others to perform. This would change by the mid-1960s, by which time she was not only composing, but arranging for, conducting and playing with the finest jazz instrumentalists of the day. Her list of collaborators from this time period is stunning: besides Bley, trumpeter Don Cherry, saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Gato Barbieri, and drummers Paul Motian and Andrew Cyrille.

This career expansion coincided with her second marriage, to trumpeter Michael Mantler, in 1965. Together they formed the Jazz Composers Orchestra Association, a non-profit collective for experimental instrumentalists that both enhanced her influence within the jazz community and provided her the opportunity to record under her own name. The albums she recorded with Mantler and under the JCOA banner represent her earliest studio performances and document her growing stature as a free-jazz artist.

Bley earned some of her biggest career breaks during these years. She wrote her first extended composition, A Genuine Tong Funeral, for vibraphonist Gary Burton in 1967, a showcase for large ensemble that presaged her later long-form pieces. Bassist Charlie Haden asked her to arrange and write for his inaugural leader release, Liberation Music Orchestra, on Impulse Records in 1969. And in 1971 she released the JCOA recording that would cement her reputation as a composer: the eclectic modern opera Escalator Over The Hill, a nearly two-hour extravaganza of jazz, Indian classical music, rock and electronics, with 20 vocalists and nearly 50 instrumentalists. It had taken three years to write and record.

These successes culminated in a wealth of attention the following year, a professional turning point for Bley. In 1972 Escalator Over The Hill garnered critical accolades and her first industry awards, and the Guggenheim Foundation granted her a fellowship for music composition. (Her fellow recipients in the jazz category that year were Keith Jarrett, Sonny Rollins, Mary Lou Williams and Meredith Monk.)

It was in 1972, too, that Bley and Mantler began to expand their music business operations. To address the major record companies’ lack of interest in releasing experimental music, the two launched the New Music Distribution Service, a branch of JCOA that brought their members’ albums to the public through a consortium of small distribution companies. Among them was ECM, Manfred Eicher’s new label; Bley and Mantler distributed Eicher’s releases in the U.S. and in return gained access to ECM’s overseas markets.

NMDS was no small undertaking. During its 18 years of operation, the service would help foster the recording careers of composers like Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, John Zorn, Sonic Youth, Gil Scott Heron and Keith Jarrett. (NMDS also was the initial distributor for Chick Corea’s first electronic jazz album, 1972’s Return To Forever. But when demand for the album threatened to crash the service’s grassroots infrastructure, ECM took over distribution for the now-classic recording.)

Most notably, however, in 1972 Bley and Mantler formed WATT, their own independent record label — a rarity at the time. Bley would make her leader debut on the label in 1974 with Tropic Appetites, her first of almost 30 leader albums on WATT to date. (The WATT label continues to exist, but Bley has not released an album on the imprint since 2009. In 2012, she signed as an ECM artist.)

Now a formidable figure in the jazz world with proprietary access to the listening public, Bley’s creative autonomy expanded further with the formation of the Carla Bley Band in 1977. The group — a rhythm section and six horns — gave Bley a ready vehicle for international touring and recording. With this band she released several albums in rapid succession, among them her first movie soundtrack, Claude Miller’s Mortelle Randonnée. Arguably, the band lineup, though shifting, contained some of the most versatile players around: drummers Steve Gadd and D. Sharpe, trombonists Roswell Rudd and Gary Valente, saxophonist Carlos Ward, and pianist Arturo O’Farrill, then a teenager.

Bassist Steve Swallow, a longtime sideman for Gary Burton and veteran of the Stan Getz Quartet, joined the group in 1978. Swallow had first befriended the Bleys in the 1950s and had worked with both off and on since; it was from this vantage point that he had observed Carla’s rise to prominence. He came to play a larger role in both her music and her personal life in the 1980s, long about the time of a major departure from her established jazz identity — and, perhaps, her largest encounter with critical disfavor.

“There was a period when she went soulful, to the consternation of the critics who loved her for her earlier work,” Swallow said in a phone call with DownBeat. “All of a sudden she’s writing what sounds like FM radio music. She really wanted to write that, and did so at her peril. She knew that she was burning some bridges.”

The albums Heavy Heart (1984), Night-Glo (1985) and Sextet (1987) derive from this period of Bley’s fascination with soul and r&b music. Despite the seeming abruptness of Bley’s mid-career embrace of these pop idioms, however, her interest in African-American music forms was long-standing. During the early 1960s, Swallow recalls, he would find Bley listening to Motown — she especially loved The Supremes — at the same time that she was writing “really abstruse, difficult music” for the experimental musicians with whom she’d started out.

“Eventually this streak rose to the surface. It took 25 years to do so,” Swallow said. “[Her] soulful music was not well received [then]. But now it’s beginning to have its day. A lot of young players have found something in this music that has lain dormant for a couple of decades. In fact, it’s one of my favorite periods of her music. I loved playing it and still do love it. I think it has great value.”

In the midst of her Motown-influenced period, Bley and Swallow also started to play duets together, first for the fun of it, then professionally. This creative venture reflected the growing closeness in their personal relationship, a partnership that continues to this day. Over the ensuing years they released several duo albums on WATT, recordings that not only provide a glimpse into the warmth of their interpersonal connection but that shine a spotlight on Bley’s riveting, deeply felt performing. (“I’ve been repeatedly admonished that it’s not enough to write the music, I have to play it too,” Bley quipped in her email.)

Even as Bley was scaling down in her duets with Swallow, she was ramping up her eponymous band. In the late 1980s she began writing and arranging pieces for a large ensemble, producing some of the most successful works of her career. Her big band would go on to tour and record for more than a decade, snagging three Grammy nominations for best large jazz ensemble, the Prix Jazz Moderne in France and multiple commissions during that time.

“There was a point in her development where she felt she had to stand up and be measured by others against [classic big band arrangers] Ernie Wilkins and Neal Hefti and Thad Jones and all of the rest of them. She went very deliberately from a medium-sized band to a full big band — four trumpets, four trombones, five reeds, rhythm section,” Swallow said. “It was a very conscious choice on her part to confront that paradigm and make a statement in that context.”

Bley continues to write for big bands — most recently for O’Farrill’s Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra in 2020 (“Blue Palestine”) and the Danish Radio Big Band in 2017 (“Roller Coaster”). But by the turn of the new millennium, Bley’s primary focus as a composer had switched to chamber works for smaller ensembles, seeming extensions of a new trio with Swallow and saxophonist Andy Sheppard.

Begun in 1994 with the release of the live album Songs With Legs (WATT/ECM), the Carla Bley Trio today is the composer’s longest-lasting ensemble. It also has served as an exquisite platform for her development as a pianist over these years.

“She’s become a player, and it’s been a lengthy road — but there’s no denying that she’s become one,” Swallow said. “One of the things I love most about her playing is that the line between her writing and her playing is kind of blurred. She plays with great deliberation, as if she were writing, but responding to the need to make it up in the moment, to play without the eraser in her hand.”

In February 2020, the trio released their third album for ECM, Life Goes On, recorded in Italy at the end of an extensive 2019 European tour. The blues-based title cut hints — with poignant levity — at Bley’s recovery from brain cancer in 2018, a difficult year of health setbacks and cancelled tour dates.

Since its release, the trio has had little opportunity to tour with the album, given the onset of the global pandemic last March. But Bley, now in remission, hasn’t missed the road much.

She’s happy to stay home, working on the next trio arrangement — a “half hour of challenging music called ‘Bells And Whistles,’” she wrote. As a composer, first and foremost, Bley is quite comfortable with this part of the creative process, waiting for the next serendipitous twist or turn.

“The key moments in my life as a composer have occurred quietly and privately, at the desk or at the piano. If you were with me when I had one, you’d hardly notice,” Bley wrote.

“Composing is solitary and unspectacular. You work hard for days and weeks, and then unexpectedly you hit upon something of value and everything is changed.

“It is such moments that form the trajectory of your life’s music, that bend it in ways you can’t anticipate.” DB

Quincy Jones’ gifts transcended jazz, but jazz was his first love.

Nov 5, 2024 1:00 AM

Quincy Delight Jones Jr., musician, bandleader, composer and producer, died in his home in Bel Air, California, on…

“I treat every day like it’s Thanksgiving,” said Roy Haynes.

Nov 19, 2024 12:57 PM

Powerhouse jazz drummer and bandleader Roy Haynes died Tuesday in Nassau County, New York. He was 99. One of the few…

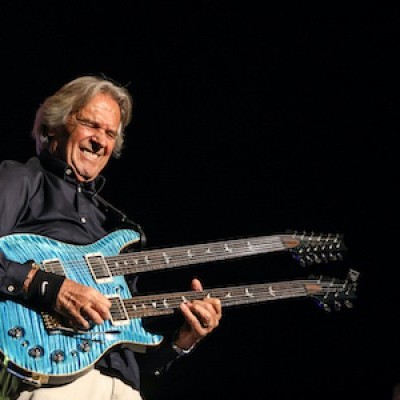

John McLaughlin likened his love for the guitar to the emotion he expressed 71 years ago upon receiving his first one. “It’s the same to this day,” he said.

Nov 7, 2024 2:17 PM

In the aftermath of World War II, the deprivations felt throughout the United Kingdom were particularly acute in John…

Lou Donaldson was one of the originators of the hard bop movement in jazz back in the 1950s.

Nov 12, 2024 12:12 PM

Alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson, the final surviving member of the original Art Blakey quintet that in 1954 introduced…

“Watching people like Max Roach or Elvin Jones and seeing how they utilize the whole drum kit in a very rhythmic and melodic way and how they stretched time — that was a huge inspiration to me,” Hussain said in DownBeat.

Dec 17, 2024 9:58 AM

Tabla master Ustad Zakir Hussain, one of India’s reigning cultural ambassadors and a revered figure worldwide…