Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

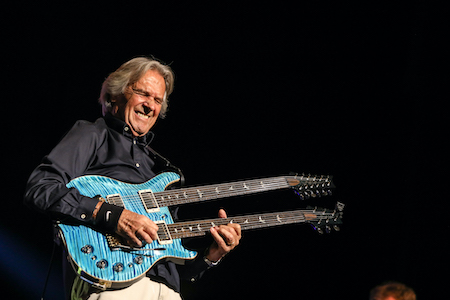

John McLaughlin likened his love for the guitar to the emotion he expressed 71 years ago upon receiving his first one. “It’s the same to this day,” he said.

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)In the aftermath of World War II, the deprivations felt throughout the United Kingdom were particularly acute in John McLaughlin’s native Kirk Sandall, a tiny village in the north of England where a munitions factory that had dominated the local economy was struggling to reorient itself in peacetime.

But to the 5-year-old McLaughlin, all that mattered little. A coal fire burned in the grate, his stomach was full thanks to his mother’s judicious use of ration coupons and, owing to her penchant for Western classical music, the sounds of Beethoven, Bach and Benjamin Britten filled the air — providing a steady diet of cultural enrichment.

So it is perhaps unsurprising that when a potentially transformative cultural moment presented itself, he was, despite his tender age, primed to respond. And that is what McLaughlin did when, sitting in the living room listening to the radio with his mother, he heard the vocal quartet near the end of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony burst forth.

“Something happened to me,” he said. “I got goose bumps all over my body. I didn’t know what it was and I told my mother. She was really happy. She said, ‘That’s music, real music. That’s what it does to you.’ I think this marked me deeper than I could have imagined. It might be the point of departure for me in future years.”

Those years have seen plenty of goose bumps raised — on both McLaughlin and those who have witnessed his mystical guitar powers applied to some of the most potent music of our time, from the swinging ’60s London scene of Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker; to the breakout bands of electric Miles Davis and post-Miles Tony Williams; to the monumentally successful Mahavishnu Orchestra, the pioneering Shakti synthesis and beyond.

“I wanted this kind of provocation, musical provocation,” he said. “I need it to this day.”

Now 82 years old, McLaughlin takes his provocation in smaller doses. Though a short swing around India with the latest incarnation of Shakti is likely next year, he insisted he has finally quit touring after the band traveled the world in celebration of its 50th anniversary last year. His recent public performances have been largely limited to charity concerts and presentations of graduates from jazz academies near his home in Monaco.

Nonetheless, he said, the performances provide that bit of kick he craves. The young talent is abundant and obviously appreciative of the chance to work with a master. And Monegasques are culturally astute: A recent performance with three of the most gifted graduates, he said, “was a thrill for us, a thrill for them and a thrill for the audience.”

In between the performances, his contemplative side seeks the restorative stimulation of the natural environment. While the summer season was tropically wet — in fact, pouring rain on both ends of an early-autumn Zoom call between Monaco and London nearly derailed this interview — he still managed to enjoy hiking amid the splendors of the ocean, forest and a 1,500-foot mountain abutting his home.

Famous for his discipline, McLaughlin regularly begins his morning with a swim and meditation. But his asceticism these days only goes so far. He uses only wheat milk on his muesli, but he admitted — with a smile — to “compromising” by using cow’s milk in his cappuccino before turning to one of his artistic projects.

Currently, he is putting together a live Shakti album. Set to be released next year, it will include performances recorded on last year’s world tour and will feature both classics and new hits from the group’s studio collection This Moment (Abstract Logix), which won the 2024 Grammy for best global music album.

At the same time, he is working on a sketchbook. For the book, in which a U.K. publisher has expressed interest, he both draws likenesses of and relates anecdotes about people who, since the early 1960s, have helped, inspired or connected with him.

“It’s a personal homage,” he said. “It’s fascinating because it’s allowed me to recapitulate my personal history and my musical history. They are intertwined.”

That history began well before the ’60s, when his mother, an amateur violinist, tried to teach him the instrument. He rebelled and turned quickly to the family piano, taking lessons from a rap-on-the-knuckles teacher who, in retrospect, seemed “a real monster.”

By the age of 10, the teacher’s influence was waning as that of his brothers waxed. When the early ’50s blues boom swept across the universities in the U.K., the oldest brother, a university student, bought a guitar that was ultimately passed down to him. He was 11.

“I quit taking piano lessons immediately and it was love at first hearing,” he said.

Exposed to blues albums by his brothers, he began absorbing that music’s language. At 15, now living near a larger northern city, Newcastle, he gained access to DownBeat, feeding his nascent interest in jazz. “To a teenager living in the upper reaches of northeastern England,” he said, “it was the holy grail.”

Meanwhile, his fondness for flamenco music was growing, and he began to skip school and trek 150 miles to a pub in Manchester to see live performances by a celebrated exponent of the music, guitarist Pepe Martinez.

“That was really another pivotal period in my life,” he said, “and I’m sure it manifested itself all those years later when I hooked up with Paco [de Lucia, with whom he formed an acclaimed trio with, alternately, Al Di Meola or Larry Coryell].”

He was also falling for Spanish-inflected jazz, courtesy of “Blues For Pablo,” off Miles Ahead, the 1957 album by Davis with Gil Evans’ orchestra. His passion for that work presaged his later identification with a mindset that became a movement melding disparate musical forms.

“What they were doing between this big band, the blues and the Hispanic thing,” he said, “that’s fusion, jazz fusion right there. It just blew me away.”

After stumbling initially at jazz — an attempt at negotiating “Cherokee” at the expected breakneck pace with experienced musicians in a local pub resulted, he said, in “blood on the floor” — he recovered and his reputation as a teen whiz grew to the point where a touring musician hired him. He was on his way to London.

“That’s what I’d been dreaming of for a year,” he said. He was around 19 years old.

In London, he made ends meet with odd jobs like driving cars and selling caviar until he landed a position at Selmer’s legendary music shop on Charing Cross Road, a musicians’ hub where he sold Pete Townsend what he believed was Townsend’s first guitar.

Gigging soon won out over Selmer’s. At Soho’s Flamingo Club he became a regular in Georgie Fame’s popular R&B-laced jazz band. At the nearby blues venue the 100 Club, he met Eric Clapton. Players mixed after hours, and he met Bruce and Baker.

When organist Graham Bond invited McLaughlin to form a quartet with the bassist and drummer — who would, of course, achieve renown with Clapton in Cream — he “couldn’t say no.”

Fame’s smooth sound, he said, was no match for the promise of playing with passionate — “sometimes over-passionate” — musicians who would “push me out of what I know to what I don’t know.”

And when that group broke up, McLaughlin signed on with the rigorous Ray Ellington, with whom he polished his sight-reading. That, in turn, led to session work that was well-paying but unsatisfying and, after 18 months, he unceremoniously quit.

But he fortuitously hooked up with a couple of fellow northerners, organist Mike Carr and drummer Jackie Denton. They provided entrée to London’s premier jazz club, Ronnie Scott’s, periodically playing opening sets. That put him on the road to New York and an association with Williams.

The road involved some benign subterfuge. Bassist Dave Holland, McLaughlin’s sometime roommate, played in the house band accompanying traveling jazz headliners. When drummer Jack DeJohnette came through — with pianist Bill Evans’ complete trio, relegating Holland to playing opening sets — DeJohnette set up an afternoon jam session at Ronnie’s. Holland brought McLaughlin.

“Jack recorded it with these Mission Impossible tape machines,” McLaughlin recalled, noting the surreptitious nature of the taping, “and that’s how I got the gig with Tony. Back in New York, Tony was saying, ‘I’m leaving Miles, I’m looking for a guitar player.’ Jack said, ‘I made a tape with this guy in London. Listen to this.’ And I got the call from Tony. How lucky.”

In 1969, the year he arrived in New York, Williams, coming off his time with the second great Davis quintet, was leading a charge among jazz players seeking to unleash their inner rocker. His answer was the incendiary Lifetime, with McLaughlin and organist Khalid Yasin, then known as Larry Young.

Baffling to some and beloved by others, the trio’s tightly wound, highly volatile interplay signaled the emergence of an audacious new sort of collective performance rendered by a group of impossibly resourceful 20-somethings operating in fly-by-the-seats-of-your-pants mode.

“We didn’t know really where we were going except that we wanted to play together and discover as we went along,” McLaughlin said. “It was constant learning and experiments. Tony was pretty free with Miles but with his own band he was really free.”

The interplay’s apotheosis is arguably an 8-plus-minute “Spectrum,” a McLaughlin composition off their debut album, Emergency!, that manages to project a quality both raw and highly defined. By comparison, the 3-minute quartet version on McLaughlin’s debut album, Extrapolation, seems tame. Both were recorded and released in 1969.

Like Williams, McLaughlin said, Davis was flying blind as the ’60s were ending. “Miles was going on intuition when we moved into Bitches Brew,” he said. “He didn’t really know what he wanted to do. But he knew what he didn’t want to do, which was what he’d been doing for the last five years.”

When the trumpeter sought to gain direction via the guitarist’s input, McLaughlin, drawing on his London experience, was happy to oblige.

“I had been hanging out a lot with Miles at his home in between In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew,” he recalled. “I’d always take the guitar over there. He made sure I survived. He’d stuff money in my pocket. And he’d be picking my brain about all the stuff I’d been doing in the ’60s with R&B and funk bands.

“‘What would you do if I played two chords like this, John?’” McLaughlin said, quoting Davis in a reasonable imitation of his raspy voice. “I’d say, ‘I could do this and this, and if I turned around I could do that.’” That simple advice seems to have been liberally incorporated in some of the most provocative jams Davis — or anyone — has ever produced.

For a time, McLaughlin played with both Davis and Williams. But he was moving on musically while Williams was seeking broader appeal for Lifetime. Having met Bruce through McLaughlin, Williams hired the bassist and asked him to sing, giving the band, McLaughlin said, “a slightly more Cream element.

“Tony wanted us to have more success. We were struggling. People were looking at us like, ‘What are they doing?’ And the jazz community, they were saying, ‘Jazz? We don’t even know what it is.’ I was surviving basically because I was doing Miles’ gig.”

That gig came to an end as a full-time endeavor when, after a less-than-satisfying night at Lenny’s on the Turnpike in Massachusetts, Davis advised McLaughlin to start his own group.

Enter The Mahavishnu Orchestra, which instantly became a juggernaut, revered for its technical prowess, to be sure, but also its transcendent writing and execution that, powered by Billy Cobham on drums, tempered with deep groove the complex Carnatic rhythms and melodic systems it had assimilated.

Tablaist Zakir Hussain, a lynchpin of Shakti, recalled that on hearing the first strains of McLaughlin’s guitar amid the disorienting swirl of sound on the oddly accented opening bars of “Birds Of Fire,” at the Berkeley Community Theater in November 1972, “my jaw dropped to the floor.”

But the band, in its first incarnation, flew high only to crash and burn — a turn of events that, in McLaughlin’s telling, reflected the stress of sudden success compounded by the members’ differing lifestyles.

“It was multiplying and multiplying too quickly,” he said. “And don’t forget by this time I’m meditating every day. I’m not hanging out. The other guys can do that. I go back to my room, have a salad and go to sleep and meditate. I was on another trip.

“Too much success is very dangerous, because it actually destroyed the band in the end.”

Among McLaughlin’s bands, none has had the longevity of Shakti. It may not have been the first to mix Western and Eastern music: John Coltrane most famously did so, even titling a tune “India,” off his 1962 album Live At The Village Vangaurd.

But McLaughlin has taken a risk Coltrane didn’t by surrounding himself and documenting his work with Indian musicians, thus subjecting himself to the necessity of adjusting to their culture of sound, even as they adjusted to his.

Hussain, who has been in the band since its inception, detected movement toward a full accommodation by their second album, A Handful Of Beauty. Unlike the first, Shakti With John McLaughlin, it was a studio recording in which “we found a way to give back to John from our side of the world.” Both were released in 1976.

Fast-forward to the pandemic, and that process advanced with the 2020 landmark Is That So? In it, McLaughlin, working with Shakti singer Shankar Mahadevan and Hussain, integrates a full harmonic soundscape with Mahadevan’s raga-based improvisations — “a dream I had for years,” as McLaughlin put it — in such a way that he fully asserts his Western identity without compromising the Eastern side.

“There is no way any Indian maestro would listen to Shankar riffing over what the harmonic base lays out and say that it is messing up the raga,” Hussain said, adding that the process of accommodation has continued.

Shakti’s impact is clear. Pianist Vijay Iyer, who at 52 has done as much as anyone to reconcile Eastern and Western musical perspectives, said of the group: “As a musician coming of age in the South Asian diaspora, it gave me a point of reference that was important. That stuff really clarified a lot for me in terms of what was possible.”

Saxophonist Charles Lloyd, a contemporary of McLaughlin’s who met Hussain through the guitarist and has for the past two decades played with him in the trio Sangam, spoke more broadly about McLaughlin:

“John is a deep sensitive. He knows that we live in a world that’s gone mad and he’s looking for the right note.”

Lloyd, who like McLaughlin has been inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame this year, added, “He has great facility but has a mind that can deal with the eternal verities in the sound. That’s where we meet: at a place where there is no space or time.”

For McLaughlin, time indeed seemed to fold in on itself as he likened his feeling about the guitar to the emotion he expressed 71 years ago upon receiving his first one.

“It’s the same to this day,” he said, “the love I have for that instrument.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…