Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

In Memoriam: Gordon Goodwin, 1954–2025

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

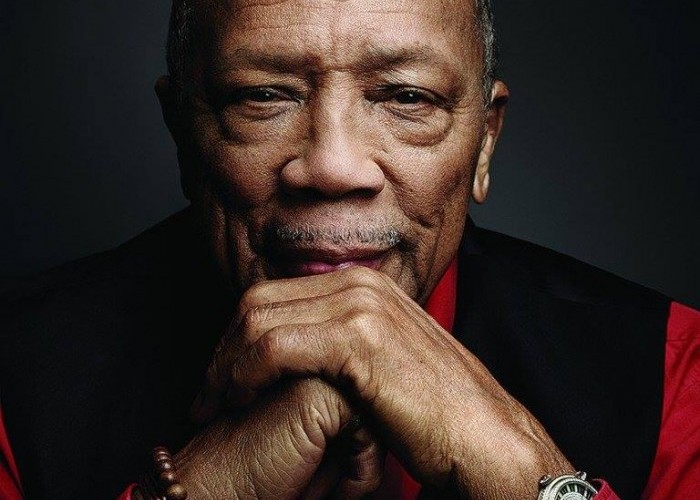

Quincy Jones’ gifts transcended jazz, but jazz was his first love.

(Photo: artstreiber.com)Quincy Delight Jones Jr., musician, bandleader, composer and producer, died in his home in Bel Air, California, on Sunday, Nov. 3. He was 91. No cause was given in a statement from his publicist, Arnold Robinson, who said Mr. Jones died peacefully in his sleep.

There are many ways of achieving great success and wealth in music. Jones’ path to that pinnacle was as unique as it was unexpected and open-ended. Ultimately it made him the only musician in jazz history to achieve the status of an authentic entertainment mogul. His great gift transcended jazz. It was to see the difference, as he put it, between “music,” which he always held close, and “the music business,” which he mastered and dominated as no other had.

Starting out with solid B+ skills as a trumpet player and pianist in the early ’50s, Jones realized that even if he could play as well as Dizzy Gillespie or Oscar Peterson — and he knew he couldn’t — that would take him only so far. So he bet instead on taking the skills he had and making them negotiable across as wide a musical frontier as possible. His greatest instrument was his sense of taste, his ability to read popular culture and his respect for all genres of American music, which he absorbed in a journey that took him from the poverty of the ghetto to an estate in Beverly Hills full of Gold and Platinum records. Somewhere under that rainbow, he found a magic touch that made him among the most influential musical forces of his generation in the wider world of popular music.

It wasn’t his music alone that carried him to the top. Like Duke Ellington, Jones had a quiet instinct for leadership that was implicit in his sheer presence and manner. It never required enforcement or coercion. In 1976 many of the most important figures in jazz, including Jones, gathered in Chicago to tape a DownBeat Readers Poll Awards show for public broadcasting. As the taping began to finish, this writer approached several musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie and James Moody, and asked what their plans were for the evening. “Not sure,” they would say. “We’ll see what Q wants to do.” People followed him because that’s where the best action was.

Born on the South Side of Chicago on March 14, 1933, Jones described himself as a “street rat.” “You want to be what you see,” he said, and most of what he saw was a world of street fighters. He painted a vivid picture of his life after his mother was institutionalized for mental illness. He lived with his father and grandmother, who was born a slave and cooked okra, possums and rats for food. He moved to Seattle in 1940 where he discovered the wonders of the piano and trumpet. Jones’ early tastes were formed both in the church and in the heyday of big band swing, which also provided him with many strong and proud Black role models. By his mid-teens he was a professional musician, playing local gigs and jamming after hours in the new bebop language. In a dangerous world, he later wrote, “music was the one thing I could control. It was the one thing that offered me my freedom.”

He got his first taste of the big time at 18 when Lionel Hampton hired him on trumpet in April 1951. The big bands were fading by then, but Hampton was still hot and booked solid. The constant traveling opened a wider world to Jones, from the Deep South to Canada and, by the fall of 1953, across Europe, Scandinavia and North Africa. For six months he sat alongside Clifford Brown and Art Farmer in the Hampton trumpet section.

It was with Hampton that Jones recorded his first original arrangement, “Kingfish.” After leaving the band in 1954, he settled in New York and began writing “for anyone who would pay.” One who was glad to pay was Dinah Washington, an earlier graduate of the Hampton band and now a major star about to do her first jazz album for Mercury’s new EmArcy label. Suddenly Jones was in demand, especially by many of the idols of his boyhood to whom he was now becoming a peer: Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Clark Terry and a boyhood friend from Seattle named Ray Charles, with whom he would collaborate on Atlantic’s Genius + Soul = Jazz. He became musical director for the Dizzy Gillespie big band that toured the Middle East in 1956, then released his first album as leader on ABC Paramount in 1957, That’s How I Feel About Jazz.

Jones had come up through the jazz world, which he loved. But professionally he was not eager to be limited by it. New York was full of music and he wanted to write and conduct all of it. He moved to Paris in May 1957, where he was not confined to the typecasting that limited Black arrangers in America. There he studied with Nadia Boulanger, French composer, teacher to Leonard Bernstein and the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic. Jones mastered the full pallet of orchestration and arranged and recorded more than 200 sessions for Barclay Records, where he served as music director while in Paris.

He returned to New York late in 1958 with a formidable resume but a reputation still rooted in jazz. He arranged Basie’s One More Time album for Roulette, then assembled his own all-star “dream band” (with Clark Terry, Harry Edison, Phil Woods) that recorded a series of dates for Mercury, where he also assumed an executive role as a director of artists and repertoire. At the end of 1959 Jones took the band to Europe with a Harold Arlen show called Free and Easy. It was neither. Costly and chaotic would be more accurate. The tour collapsed in a couple of months, about the time of his first DownBeat cover in February 1960. The band struggled on through the summer, then came back to America $145,000 in debt. It continued to work through 1961, playing the Newport Jazz Festival that year.

“If there is a ‘real’ Quincy Jones,” jazz producer and historian Michael Cuscuna wrote in 1983, “it probably lies in this energetic midpoint in his career, when his band was his voice.”

Nevertheless, it would be the watershed of his professional life, the moment he came to understand the difference between the art and commerce of music. He chose to turn his passions toward the commerce side. From this point on, Jones would maintain his profile in the jazz world increasingly as an avocation, although he always rejected such categorization. “People get all hung up with the evolution of this music and that,” Jones told writer Zan Stewart in a 1985 DownBeat cover story. “[They say] ‘You’re not into jazz anymore.’ Bullshit. It’s all the same thing to me … . Those skills enable you to turn on a dime. You don’t get hung up on the way things are supposed to be.”

Jones was promoted to a vice presidency at Mercury, the first African American to achieve such rank in a major record company. His job now was to find hit records. Jones understood that all popular music is sociological — a useful insight that would sustain him into hip-hop. Unwilling to be typecast to the “Negro” market, he cast a wide net and found Lesley Gore. When “It’s My Party” went to the top, Jones became a hit maker. The calls started coming. In July 1963 he reunited with Count Basie to arrange his first album with Ella Fitzgerald, Ella And Basie, for Verve.

That project may have prompted another call he received in 1964. It was from Frank Sinatra, who thought Jones would be the perfect architect to engineer a long-standing ambition of his, a Sinatra-Basie album. The result was It Might As Well Be Swing on Reprise, the first of several collaborations they would do. Nearly 20 years later, after teaming with Lena Horne for her Broadway success The Lady and Her Music, Jones was ready to undertake another of his dream projects, a Sinatra-Horne album.

Those plans didn’t materialize, but these close associations perfectly illustrated his strategy of leadership among the royalty of American music. In the studio Jones was a collaborator, never an adversary. He listened carefully to what an artist wanted and could make musical fixes on the fly and keep moving. His efficiency and assurance in the pressure of the studio was a comforting presence. “Frank was just my style,” Jones later wrote. “Hip, straight-up and a monster musician.” He called the project a turning point in his career. When the astronauts lauded on the moon, they played Quincy Jones’ chart of Sinatra’s “Fly Me To The Moon.” And his work with Horne produced both Tony and Grammy Awards.

Sinatra brought Jones into the inner circle of popular entertainment at the highest imaginable level. The power was so palpable you could see it. Sinatra’s friendships with Jones, Basie and Sammy Davis ended Jim Crow in Las Vegas almost overnight. It taught Jones some things about using power softly. He projected charm, support and love in all directions, and earned the trust of the mighty. But his openness and ease with people extended to everyone. Several years ago this writer contacted him for a short phone interview on Hank Jones. After answering questions, he began asking others — about what I did, what I liked, who I knew. The conversation went on for nearly 45 minutes, after which we exchanged email addresses, phone contacts and practically social security numbers. That was my brush with the famous Quincy Jones treatment. I understood why he had such a vast network of contacts and friends.

Jones moved to Los Angeles in the early ’60s because he wanted to try film scoring, a field that no African American composer aside from Duke Ellington had successfully breached. He began in 1963 with a low-budget Sidney Lumet success, The Pawnbroker. More than 40 major Hollywood productions followed, along with three Oscar nominations: Walk, Don’t Run, In Cold Blood, In the Heat of the Night, The Italian Job, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, They Call Me MISTER Tibbs!, The Getaway,The Wiz and Roots.

Success took its toll. In 1974, at age 41, he suffered a brain aneurysm that left him with a 1 percent chance of surviving. Surgery fixed the problem but uncovered a second aneurysm in the process. There would have to be a second operation. With his future in doubt, a memorial service was scheduled, which he attended along with an honor roll of music and film stars. Against deep odds, he recovered. In 1975 he founded Qwest Productions, which became the parent operation of his various records and TV projects.

In the ’70s music in America got funky and Black culture went mainstream. While making The Wiz in 1978, Jones met Michael Jackson, who was looking for a producer. Jones saw his potential beyond his bubblegum history as well as his need for special handling. He decided he could do it. Jones became Jackson’s mentor and almost a father figure. When Off The Wall came out on Epic a year later, it sold 20 million copies, a record for a Black pop artist, and produced four top singles. It was only the beginning. For Jackson’s next, Jones auditioned hundreds of songs, selected 12 and produced Thriller. What Stephen Spielberg had done for the economics of Hollywood, Quincy Jones seemed to do for the record industry, which was to redefine the ceilings of success. By the time he accepted his Grammy as Producer of the Year in 1982, Thriller was about to become the biggest selling record in history.

Naturally, the next logical move was a partnership between Spielberg and Jones, now the two presiding tycoons of the entertainment world. It converged in their mutual interest in Alice Walker’s 1983 novel The Color Purple. It was Jones who brokered the partnership between Spielberg and Walker that ultimately brought the work to the screen in 1985. She was reluctant to let Spielberg do it until Jones talked her into meeting with him and hearing his thoughts. Jones was also producer and wrote the score. Twenty years later he also produced the successful musical adaptation that came to Broadway.

Ten days before The Color Purple opened on Feb. 7, 1985, Jones used his diplomatic skills and influence to engineer and produce one of the most famous confluences of contemporary talent in history — the We Are The World taping in A&M Studios, which brought together in one room a choir of voices that included Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Michael Jackson and 45 other stars of comparable stature.

It was perhaps the most intense period of productivity in his career. By the middle of the ’80s, however, he began taking time for a few sentimental personal projects focusing back on jazz. In 1985 he produced and conducted his final Sinatra project for Qwest Records, L.A. Is My Lady, in which he made space for cameos by Jerome Richardson, Frank Wess, Michael Brecker and even his original boss, Lionel Hampton. In 1989 he brought Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan together for his Grammy-winning Back On The Block album. And finally in 1991, after years of effort, he achieved his most impossible dream: reuniting Miles Davis with a group of his early classics with Gil Evans. Jones conducted what would become Davis’ final performances in a concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival.

In the ’90s he founded Vibe magazine, which he hoped would be to the hip-hop generation what DownBeat was to jazz and Rolling Stone was to rock. Jones was an advocate of rap’s verse formats and tried to see it in a line of descent from bebop. But the violence of hip-hop culture disturbed him and made him advocate simultaneously for an awareness among young Blacks of their larger cultural history. He was an active supporter of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

In his later years he found the time to consider his body of work more philosophically, as he collected an endless series of awards and tributes for what he had achieved. These include 79 Grammy nominations and 27 wins, the National Medal of Freedom and, most importantly, the Kennedy Center Honor in 2001 — where Ray Charles moved him to tears singing “My Buddy” from the stage.

Quincy Jones is survived by a brother, two sisters and seven children. DB

Goodwin was one of the most acclaimed, successful and influential jazz musicians of his generation.

Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Dec 11, 2025 11:00 AM

DownBeat presents a complete list of the 4-, 4½- and 5-star albums from 2025 in one convenient package. It’s a great…