Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

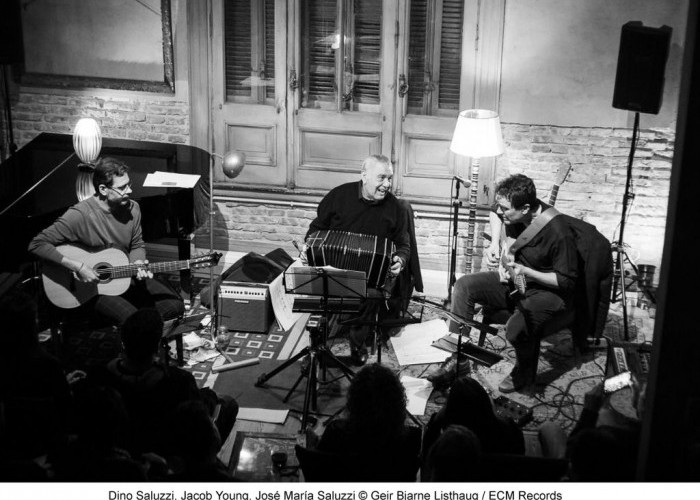

Dino Saluzzi, center, flanked by José Maria Saluzzi, left, and Jacob Young.

(Photo: Geir Bjame Listhaug/ECM)In some way, the sublime new album by venerable bandoneon player Dino Saluzzi, El Viejo Caminante, is a family affair on two accounts. In the unique format of the leader joined by classical and steel-string guitar, Saluzzi continues his direct family link with his son, guitarist José Maria (on classical guitar). By inducting Norwegian guitarist Jacob Young (steel-string acoustic and occasional electric guitar) into the project, Saluzzi taps into his strong and ongoing link with the ECM Records “family,” a discographic lineage going back more than four decades.

Saluzzi, who turned 90 on May 20 of this year, may have ceased traveling from his Argentina base, but he is otherwise actively engaged in the arc of his deep and extended musical journey, in which El Viejo Caminante is another moving example. On this set of originals and the standards “Someday My Prince Will Come” and “My One And Only Love” (in freely abstracted versions), Saluzzi’s trademarked organic melodicism and sense of space and grace are fully in check, effectively complemented by the accomplished, ever-sensitive guitarists.

DownBeat recently checked in with the trio thanks to the transponder facilitation of Zoom, with the Saluzzis in Buenos Aires, Young in his home outside of Oslo, Norway, and this scribe in Santa Barbara, California. The transnational connection seemed apt, considering the cross-cultural feats navigated by Saluzzi in his long career — especially on his ECM work.

The new album’s back story is a long and winding one, going back to the impetus of a specific song. José Maria found himself enamored of the tune “Terese’s Gate,” from Young’s 2014 ECM album Forever Young, and immediately reached out to compliment the Norwegian guitarist. A year later, Young told José of plans to visit Argentina and asked about getting together.

“Right away,” José recalls, “I thought about organizing a gig, playing with my band, and him as well as a guest. My father came to the concert, and he had the idea to put us three together. It reminds me a little bit the old days from ECM, when it was more common that some musicians from different parts of the world meet together to play and make an album. It didn’t need to be a band or a group. I caught that feeling a little bit when I listen to our record now.”

In the interview, Dino expanded on the idea of creative pan-cultural discourse, something he is well versed in. “Everybody knows we are musicians,” Dino says. “We play instruments. But the more and more important thing is to put to people all over the world together, to have a possibility for everybody over the world, to take out our differences. Now we are in a confused situation, and the artistic and all the spirits manifestation make everything possible to (trigger) the feeling (of a connection), through the sounds, the painting, through the stories. We need this more than ever now.

“I’m 90 years old now. It’s a little bit difficult to travel 15,000 kilometers and, on the way to back, another 15,000 kilometers, and then play, because the energy is not the same. So, for me, it’s very important to have musical possibilities in my country, in my home. And Jacob is a nice guy, good musician.

“Another very important subject is that we have different ways of playing, because we come from different cultures, but the music is the music. The art is an art. We’re working with honesty.”

On the album, Dino’s legacy and early years are alluded to with his wistful and nostalgic tune “Buenos Aires 1950,” echoing his time as a fledgling musician from the rural city of Salta, working with the Orchesta de Radio el Mundo.

“I was 24, 25 years old,” he says. “If you listen to Black people from the country, it is almost the same because I come from the countryside, too. In the middle of the jungle, I study my instrument. Salta is a very small town. At 9:30, 10 o’clock, no electricity.”

His musical voice traversed the indigenous sound of tango into aspects of jazz. “Tango,” he says, is “a way for us to say jazz, too.”

Young, originally from the small Norwegian town of Lillehammer, who has become a worldly artist — geographically and stylistically — explains that Dino’s origin story “is a part of the tradition of improvisation that I come from. It’s very similar with the way I understand Dino and José. They’re from a different, more folkloric and Argentinian tango tradition, but it’s also improvisation, also playing in the moment. It’s about listening and phrasing and making a story together. It’s the same elements.”

Dino’s new album falls in line with much of his previous work, which can move between worlds of concept, traditions and ultimate expression. “With any art expression,” he says, “it is a little bit like being part of an experimenting process.

“You are never secure, maybe. But maybe everything makes sense when the thing you’re doing makes you happy, and makes other people happy. Then it makes everything more reasonable. But sometimes you don’t know everything. It’s a mystery, also. You put a big part of your wishes and your capacity into the project, and you can know a lot, but in the end, it’s a risk.”

Young adds that, with this project, “We had no idea if it was gonna work or what it’s gonna be or anything. We just said, ‘Let’s do it.’ And we did. The spirit was very positive, but we didn’t know what it was gonna be. It could be anything, almost.”

And the end result does work, and sing, with a mature-yet-fresh sonic palette.

Dino’s impressive and cohesive body of work on ECM goes back to the label’s hands-on founder-producer Manfred Eicher inviting him aboard and releasing 1982’s solo bandoneon recording Kultrum, followed soon after with Once upon a time–Far away in the south (Dino Saluzzi, Palle Mikkelborg, Charlie Haden and Pierre Favre, 1986). Later projects found Saluzzi in collaboration with the Rosamunde Quartette (Kultrum, 1998); a duet album with another Norwegian, drummer Jon Christensen (Sendero, 2005); and a particularly fruitful affiliation with German cellist Anja Lechner, as well as albums with his sons along the path.

“We have been very lucky to have Manfred behind us,” Dino says of his ECM bond. “Manfred is a very important person, all over the world, for the music. That means we are able to play and record now. I remember when we met for the first time, at the Molde festival (in Norway). We were talking there and he offered to make a record there. He put me with the musicians who he said I would be more comfortable with.

“We made the first album at the studio in Ludwigsburg. I receive everything from the music. From the music I received love, friendship, and I started to know very important people. I started to learn how to discover these unbelievable people who play this music called jazz — (which was) like what we call tango.”

The nonagenerian bandoneon master and poet continues on his quest and trek. “I practice every day,” he explains. “To play bandoneon, I need strong energy. To make a good sound from the bandoneon, we need to expend great force. I make a composition. I write almost every day. I need to come back to this time, but it’s difficult now, because life … to meet with my friends ... I made so many friends in my career. One trumpet player I played with was Tomasz Stanko, and also the Italian guy, Enrico Rava. I have a thousand friends, in music, writing, painting. The world of the arts is unbelievable. It’s another way of being. It’s a kind of authority that we need. I don’t want to make me sad, but I miss that. With Anja, we played almost 12 years. Also, I left behind many musicians who gave me a lot of energy and knowledge and friendships. Some of them are not here anymore, but were a big part of my career.

He suddenly directs his attention to the Norwegian on the Zoom call: “We have to make another album, Jacob, called La Vida de Musicos.”

Young jumps in: “I’m in! I’d love to go back to Buenos Aires, soon.”

You heard it here first. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…