Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

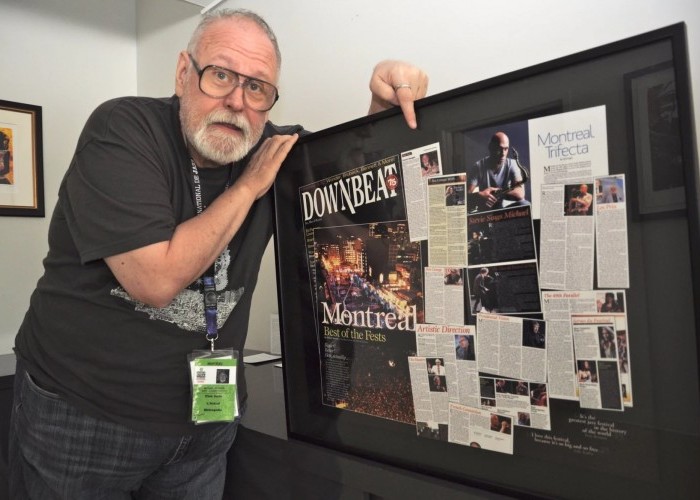

Michael Bourne shared his exuberance and enthusiasm for jazz with gusto, be it on the radio or in the pages of DownBeat.

(Photo: Courtesy NPR)The DownBeat staff had to remove the name of a favorite contributor from the magazine’s masthead this month. Michael Bourne, who had been “scribbling” for DownBeat for more than 50 years, passed away Aug. 21 from natural causes. He was 75.

Bourne was a larger-than-life character on the jazz scene, and as a person. He worked as a popular DJ for WBGO, New York’s jazz radio station, based in Newark, New Jersey, from 1984 up until his retirement earlier this year, hosting the programs Afternoon Jazz, The Blues Hour and his longstanding Sunday show, Singers Unlimited. He was also the host of the American Jazz Radio Festival, a precursor to Jazzset with Branford Marsalis, which was later hosted by Dee Dee Bridgewater.

“‘I get paid to spin records,” is what Michael always told people, said Amy Niles, former president of WBGO and one of Bourne’s closest friends. “While that was true in some ways, it was the impact of how he crafted his stories through the music and his words that was really what he laid out for us all. Nothing was random in his life. You had to read his words the way he wrote them and hear the music as he presented it, but he always left the room for your interpretation, never telling you what you should see, hear or feel.

“He called himself a critic but never criticized,” she continued. “And when he told a story, about Dizzy or Rio de Janiero or Istanbul, it was because he was with Dizzy or in Rio or Istanbul. It was never just about those people and places, you were with Michael, too.

“One of the great joys about being Michael’s BFF — he called me that for 25 years because he loved to tell people that I was his boss and his best friend — was traveling with him to festivals and meeting fans. They were positive they knew his voice and his personality — until they came face-to-face with him and complimented him. “Groovy,” he would respond. Nothing more. They would take me aside and say, ‘Is that really Michael Bourne?’ as if they had just seen the Grand Canyon for the first time and had suddenly become speechless, just like he was.”

As a writer, Bourne possessed a voice that rang clear and true; one that brought a smile to many faces and served as a cheerleader for this music. He wrote as he spoke, which is one of the highest honors one writer can pay to another. His voice was authentic, energetic and positive. He saw music as something bigger than just entertainment. It was important. It mattered. And he shared that exuberance with gusto, be it on the radio or in the pages of DownBeat.

Bourne began writing for DownBeat in 1969. Many of his articles for the magazine have become iconic. There was “Fat Cats At Lunch,” a free-wheeling conversation between trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and Bourne from the May 11, 1972, edition, where Gillespie speaks eloquently about music, but also his Baá’í faith; or, Bourne’s intimate interview with Tony Bennett from 2002 where he took the singer and painter to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and discussed two of their favorite topics — music and art; or his beautiful in-depth conversation with Dave Brubeck from September 2003, one that graced the cover of DownBeat, and was also presented as a separate radio program for WBGO on Labor Day that year.

And then, there was his constant loving embrace of the Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, an event that served as his home away from home. Bourne was a mainstay at the annual festival, broadcasting, serving on panels, adjudicating bands for competitions. Montréal was his heart — big and open and not afraid to present disparate musical dynamics under that singular event. It was a festival that spoke to Bourne’s desire to want more from music, and life. The festival named the press room after him in a fitting tribute to a true critic’s critic.

“I had this principle that I had got from Goethe, and that’s that the first question a critic should ask is, ‘What is the artist trying to do?’ Bourne said in a 2017 interview with DownBeat’s Ed Enright after Bourne was honored with the Bruce Lundvall Award at the Montréal fest. “The second question is, ‘How well is the artist doing it?’ And the third question is, ‘Was it worth doing?’ And I said too many critics went right to number three, and that’s all they talk about —what they think it should be. I don’t. I go to number one, which is to try to describe what it is, to try to encompass what it is that’s happening, not saying it’s good or if I like it.”

He was born Dec. 4, 1946, in St. Louis, the only child of Russell and Martha Lowe Bourne.

He became a jazz fan after purchasing a copy of Dave Brubeck’s Time Out at a local grocery store. Hearing “Strange Meadowlark” served as his entrée into a lifelong passion for the music.

Bourne received an undergraduate degree in theater from Northeast Missouri State University (now Truman State University) and completed his Ph.D. at Indiana University. That’s where he began his broadcasting career, at WFIU Public Radio, before moving to New York in 1984. Theater was his first love, and Bourne was a voting member of the Outer Critics Circle. He was an original host of the Broadway Channel on Sirius.

“I became a jazz jock by chance,” Bourne said during a WBGO interview on the topic of his retirement. “I was working on my doctorate in Bloomington. I’d been an occasional guest on the jazz show of IU’s NPR station, WFIU. When the regular DJ was going on vacation, the program director asked me if I’d like to fill in on the show. That was the summer of 1972 and I’d just survived my doctoral exams. I needed to do something fun, plus they were going to pay me to play records on the radio. I was supposed to fill in for four weeks, but the four weeks is now almost 45 years.”

Bourne lived large, not only through jazz, but through Broadway plays and musicals, food and travel. He had a voracious appetite for the good life, with a raconteur’s flair that made him easy to befriend.

He is survived by Elizabeth Dicker, her husband, Glenn, and children Nora and Lukas. Plans for a memorial service are forthcoming. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to Actors Fund Home, actorsfundhome.org.

How did Bourne want to be remembered?

“Who knows?” he said in that 2017 DownBeat interview. “We’re all different. Nobody does what I do, and I don’t expect them to. And I don’t do what anybody else does. I never think of myself as being better or best or anything. All I want to be is unique. I want it to be what I did — and if you like it, great, and if you don’t, OK. I lost my travel legs, so I can’t meander all over Europe anymore. But I did that. And I’m really happy to have gotten the chance. Jazz took me around the world. I can’t complain. That should be on my tombstone: ‘He could not complain.’”

Rest easy, Dr. Bourne. You were a hero. We miss you already. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…